Doctor Web’s annual virus activity review for 2024

January 30, 2025

Ad-displaying trojans, spyware trojans, and unwanted adware apps were the threats most commonly detected on mobile devices. Throughout the year, increasing activity on the part of mobile banking trojans was observed. In addition, our virus laboratory discovered hundreds of malicious and unwanted programs on Google Play.

Doctor Web’s Internet analysts noted high activity on the part of online fraudsters, whose arsenal included both old and new schemes for deceiving users.

Compared to 2023, the number of user requests to decrypt files affected by encoder trojans decreased. At the same time, our specialists observed many information security incidents and events. Over the course of the year, Doctor Web investigated several targeted attacks, uncovered another infection impacting Android TV box sets, and repelled an attack on its own infrastructure.

Principal trends of the year

- Trojans created with the AutoIt scripting language remained highly active.

- Malicious scripts were among the most widespread threats.

- Malicious scripts and various trojans were among the threats most commonly detected in email traffic.

- New targeted attacks were detected.

- Threat actors exploited eBPF technology more often to conceal their malicious activity.

- The number of requests to decrypt files affected by encoder trojans decreased.

- Internet fraudsters were highly active.

- Cybercriminals used mobile banking trojans more frequently.

- Many new threats were discovered on Google Play.

The most notable events of 2024

In January, Doctor Web’s specialists informed customers about the mining trojan Trojan.BtcMine.3767, which was concealed in pirated programs that were being distributed via a specially created Telegram channel and a number of websites. This malware infected tens of thousands of Windows computers. To anchor itself in an attacked system, it created a scheduler task for its own autorun and added itself to the Windows Defender anti-virus exceptions. Next, it injected a component directly responsible for cryptocurrency mining into explorer.exe (Windows Explorer). Trojan.BtcMine.3767 also allowed a number of other malicious actions to be performed, e.g., fileless rootkits can be installed, access to websites can be blocked, and Windows updates can be disabled.

In March, our company published research on a targeted attack against a Russian enterprise in the mechanical-engineering sector. An investigation into the incident revealed a multi-stage infection vector and the use of several malicious programs by the attackers. Among these programs, of greatest interest was the JS.BackDoor.60 backdoor, through which the main interaction between the attackers and the infected computer took place. This trojan uses its own JavaScript framework and consists of a main body and additional modules. It allows files to be stolen from infected machines, keystrokes to be hijacked, and screenshots to be taken. It can download its own updates and expand its functionality by downloading new modules.

In May, Doctor Web’s virus analysts discovered the trojan clicker Android.Click.414.origin in Love Spouse, an app used to control adult toys, and also in the QRunning app, used to track physical activity. Both were distributed through Google Play. Android.Click.414.origin was disguised as a component for collecting debugging information and was embedded into several new versions of the target apps. Later, the developer of the Love Spouse program updated the app, and the trojan was no longer present in it. There was no reaction from the developer of the second program. Android.Click.414.origin had modular architecture and could perform various malicious tasks with the help of its components. It could collect information about an infected device, covertly load webpages, display ads, perform clicks, and interact with the contents of loaded pages.

In July, we informed users about the emergence of a Linux version of the well-known remote access trojan TgRat, which is used for targeted attacks on computers. Dubbed Linux.BackDoor.TgRat.2, the new variant of this malware was discovered during an investigation into an information security incident that a hosting provider contacted us about. Dr.Web anti-virus detected a suspicious file on the server of one of their clients; it turned out to be the backdoor dropper that actually installed the trojan. Threat actors controlled Linux.BackDoor.TgRat.2 through a private Telegram group, using the Telegram bot connected to it. Through the messenger, they could download files from a compromised system, take screenshots, remotely execute commands, or upload files to a computer via chat attachments.

In early September, we published an article on our website, detailing the case of a failed spear-phishing attack on a major Russian enterprise in the rail freight industry. Several months earlier, the company’s information security team had detected a suspicious email with a file attached to it. Our virus analysts’ examination of it showed that it was a Windows shortcut disguised as a PDF document, and that it had hardcoded parameters for launching the PowerShell command interpreter. Opening this shortcut would lead to a multi-stage infection of the target system, with several malicious programs designed for cyber espionage. One of them was Trojan.Siggen27.11306, which exploited the CVE-2024-6473 vulnerability in Yandex Browser to intercept the DLL search order (DLL Search Order Hijacking). The trojan placed a malicious DLL library into the browser installation directory; this file had the same name as the system component Wldp.dll responsible for securely launching applications. Since the malicious file was located in the browser directory, it received higher priority to be loaded when the program was launched, thanks to the browser vulnerability. The library also obtained all the permissions of the browser. This vulnerability was later fixed.

A little later, our specialists reported on another attack on Android-based TV box sets. In this campaign, the malicious program Android.Vo1d was used. It infected nearly 1.3 million devices belonging to users in 197 countries. This was a modular backdoor that placed its components into the system storage area and, upon receiving the attackers’ commands, could covertly download and run other programs.

Moreover, in September, we detected a targeted attack on our company’s resources. Doctor Web’s specialists promptly stopped the attempt to damage our infrastructure, successfully repelling the attack. At the same time, none of our users were harmed.

In October, Doctor Web’s virus analysts reported on the discovery of a number of new malicious programs for Linux. They were uncovered thanks to a study of attacks on devices that had the Redis database management system installed on them. This system is increasingly becoming the target of cybercriminals wanting to exploit the various vulnerabilities in it. Among the threats detected were backdoors, droppers, and a new modification of a rootkit that installs the Skidmap mining trojan on compromised devices. This miner has been active since 2019, and its primary targets are large servers and cloud environments.

Also in October, our virus laboratory uncovered a large-scale campaign aimed at distributing malware for cryptocurrency mining and theft. Over 28,000 users, most of whom were from Russia, suffered from the actions of the attackers. The trojans were hiding in pirated software that was being distributed via fraudulent websites created on the GitHub platform. In addition, the malware creators placed links for downloading malicious programs under videos posted on the YouTube platform.

In November, our experts discovered a number of new variants of the Android.FakeApp.1669 trojan, whose task is to load websites. Unlike the malware most similar to it, Android.FakeApp.1669 receives target website addresses from the TXT records of malicious DNS servers. For this, it uses the modified code of the open-source library dnsjava. At the same time, the trojan exhibits malicious activity only when connected to the Internet through certain providers. In other cases, it operates as harmless software.

At the end of 2024, while investigating a request from one of our clients, Doctor Web’s virus laboratory specialists detected an ongoing hacker campaign primarily targeting users from Southeast Asia. During the attacks, cybercriminals used a range of malicious programs as well as methods and techniques that are only increasing in popularity among virus writers. One of them involves exploiting eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) technology, which was created to provide enhanced control over the network subsystem of the Linux operating system and its processes. This technology was used to conceal malicious network activity and processes, collect confidential information, and bypass firewalls and intrusion detection systems. Another technique involved storing the trojan configuration not on the C&C server, but on public platforms such as GitHub and blogs. The third feature of the attacks was the use of post-exploitation frameworks in tandem with malicious apps. Although such tools are not malicious and are used in security audits of digital systems, their functionality and the presence of vulnerability databases can expand the capabilities of attackers.

The malware landscape

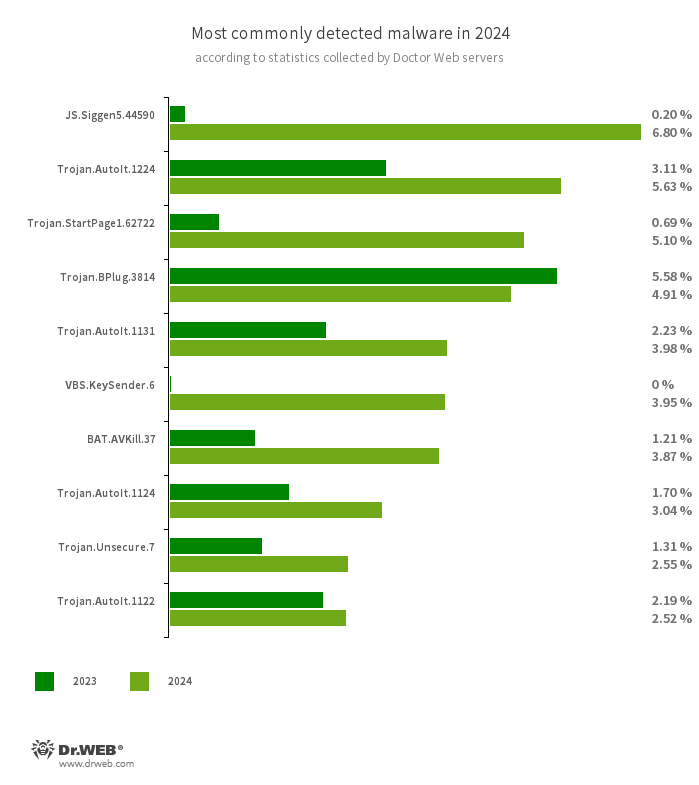

According to the statistics collected by Dr.Web anti-virus, the total number of threats detected in 2024 increased by 26.20%, compared to 2023. The number of unique threats increased by 51.22%. Among the most common malicious programs were trojans created in the AutoIt scripting language. They are distributed as part of other malware and are designed to make the latter more difficult to detect. Moreover, users encountered various malicious scripts and adware trojans.

- JS.Siggen5.44590

- Malicious code added to the es5-ext-main public JavaScript library. It shows a specific message if the package is installed on a server with the time zone of Russian cities.

- Trojan.AutoIt.1224

- Trojan.AutoIt.1131

- Trojan.AutoIt.1124

- Trojan.AutoIt.1222

- The detection name for packed versions of the Trojan.AutoIt.289 malicious app that are written in the AutoIt scripting language. This trojan is distributed as part of a group of several malicious applications, including a miner, a backdoor, and a self-propagating module. Trojan.AutoIt.289 performs various malicious actions that make it difficult for the main payload to be detected.

- Trojan.StartPage1.62722

- A malicious program that can modify the home page in the browser settings.

- Trojan.BPlug.3814

- The detection name for malicious components of the WinSafe browser extension. These components are JavaScript files that display intrusive ads in browsers.

- VBS.KeySender.6

- A malicious script that, in an infinite loop, searches for windows containing the text mode extensions, разработчика and розробника and sends them an Escape key press event, forcibly closing them.

- BAT.AVKill.37

- A component of the Trojan.AutoIt.289 malicious program. This script launches other malware components, sets them to autorun via Windows Task Scheduler, and also adds them to Windows Defender’s anti-virus exceptions.

- Trojan.Unsecure.7

- A trojan that blocks the launch of anti-viruses and other software through AppLocker policies in the Windows operating system.

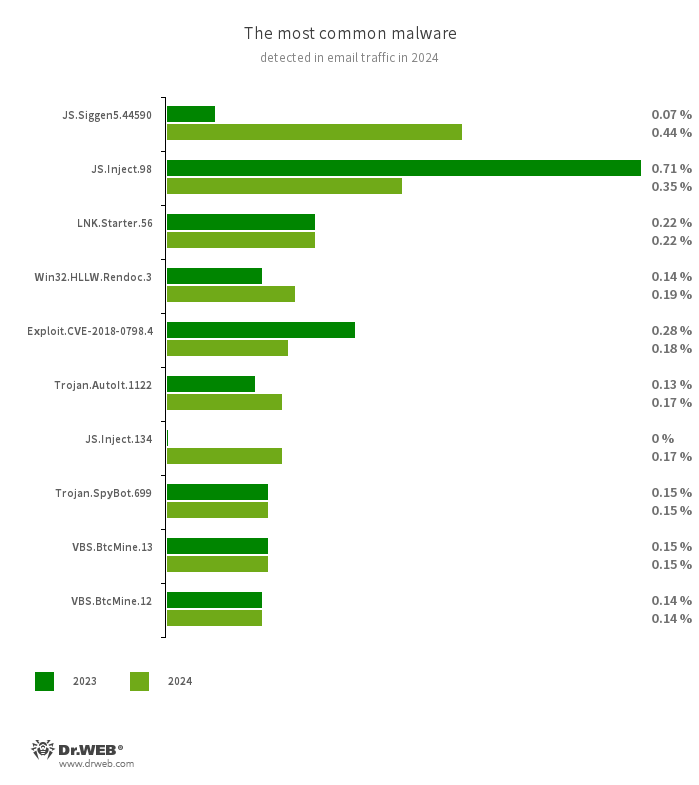

As for email threats, the most widespread were various malicious scripts and all kinds of trojans, including backdoors, malware downloaders and droppers, trojans with spyware functionality, malicious cryptocurrency miners, and others. Threat actors also distributed phishing documents, often fake login forms mimicking those on popular websites. Additionally, users encountered worms and malicious apps that exploit vulnerabilities in Microsoft Office documents.

- JS.Siggen5.44590

- Malicious code added to the es5-ext-main public JavaScript library. It shows a specific message if the package is installed on a server with the time zone of Russian cities.

- JS.Inject

- A family of malicious JavaScripts that inject a malicious script into the HTML code of webpages.

- LNK.Starter.56

- The detection name for a shortcut that is crafted in a specific way. This shortcut is distributed through removable media, like USB flash drives. To mislead users and conceal its activities, it has a default icon of a disk. When launched, it executes malicious VBS scripts from a hidden directory located on the same drive as the shortcut itself.

- Win32.HLLW.Rendoc.3

- A network worm that spreads via removable storage media and other channels.

- Exploit.CVE-2018-0798.4

- An exploit designed to take advantage of Microsoft Office software vulnerabilities so that an attacker can run arbitrary code.

- Trojan.AutoIt.1122

- The detection name for a packed version of the Trojan.AutoIt.289 malicious app that is written in the AutoIt scripting language. This trojan is distributed as part of a group of several malicious applications, including a miner, a backdoor, and a self-propagating module. Trojan.AutoIt.289 performs various malicious actions that make it difficult for the main payload to be detected.

- Trojan.SpyBot.699

- A multi-module banking trojan. It allows cybercriminals to download and launch various applications on infected devices and run arbitrary code.

- VBS.BtcMine.13

- VBS.BtcMine.12

- A VBS script designed to covertly mine cryptocurrencies.

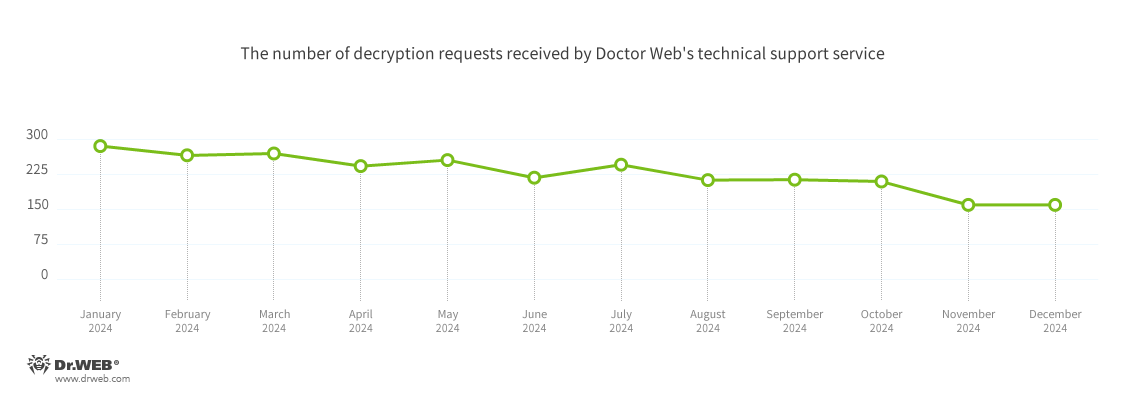

Encryption ransomware

Compared with 2023, in 2024, Doctor Web’s technical support service registered 33.05% fewer user requests to decrypt files affected by encryption trojans. The dynamics of when those requests were registered is shown in the graph below:

The most common encoders of 2024:

- Trojan.Encoder.35534 (13.13% of user requests)

- An encoder trojan also known as Mimic. It uses the everything.dll library from the legitimate software Everything, which is designed to instantly locate files on Windows computers.

- Trojan.Encoder.3953 (12.10% of user requests)

- An encoder trojan that has several versions and modifications. It uses the AES-256 algorithm in CBS mode to encrypt files.

- Trojan.Encoder.26996 (7.44% of user requests)

- A trojan encoder known as STOP Ransomware. It attempts to obtain a private key from a server. If unsuccessful, it uses the hardcoded one. It uses Salsa20 stream cipher to encrypt files.

- Trojan.Encoder.35067 (2.21% of user requests)

- An encoder trojan also known as Macop (Trojan.Encoder.30572 is one of its other variants). It has a small size, about 30-40 Kbytes. This is partially due to the fact that the trojan does not carry third-party cryptographic libraries and uses exclusively CryptoAPI functions for encryption and key generation. It uses the AES-256 algorithm to encrypt files, and the keys themselves are encrypted with RSA-1024.

- Trojan.Encoder.37369 (2.10% of user requests)

- One of many modifications of #Cylance ransomware. To encrypt files, it uses the ChaCha12 algorithm with the Curve25519 (X25519) elliptic curve key exchange scheme.

Network fraud

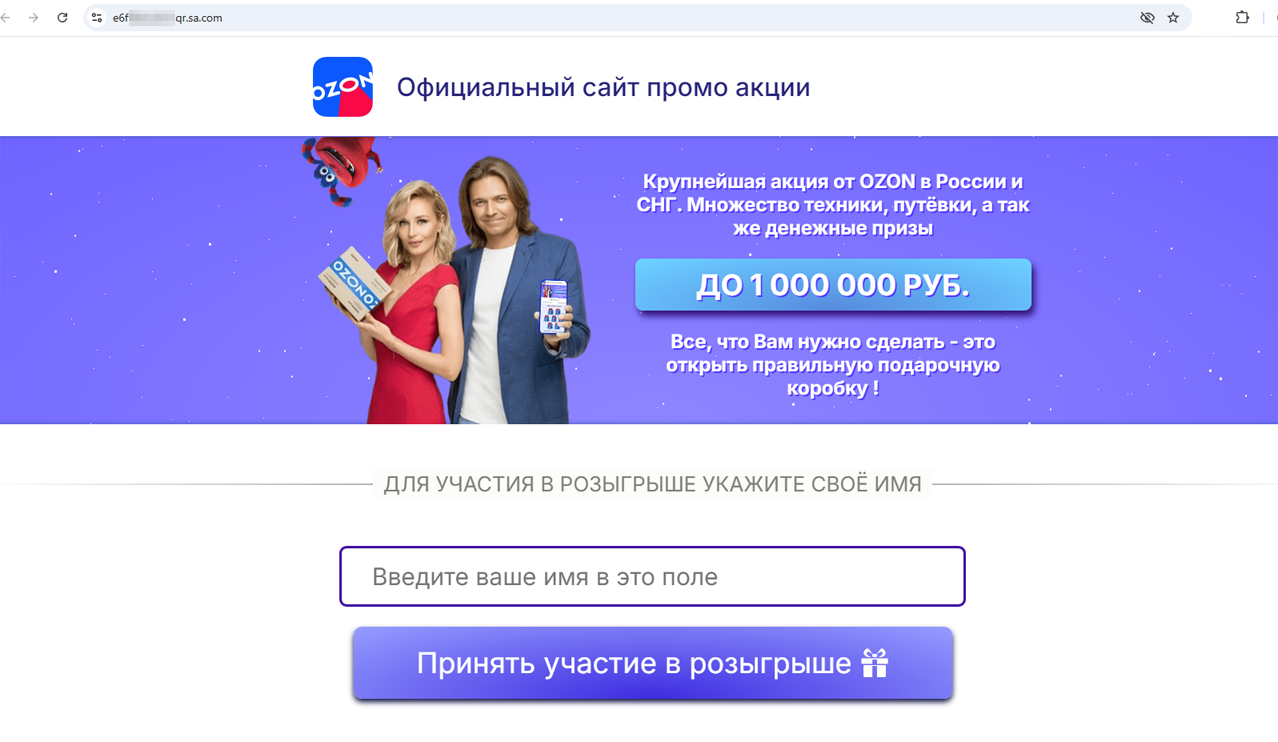

Over the course of 2024, Doctor Web’s Internet analysts observed high activity on the part of cyber fraudsters using both traditional and new scenarios to deceive users. In the Russian segment of the Internet, the most widespread schemes were again those using fraudulent sites of multiple formats. Some of them were fake sites of online stores and social networks with promotions and prize draws allegedly sponsored by them. Potential victims always “win” on such websites, but to get their nonexistent prize, they are asked to pay a “commission”.

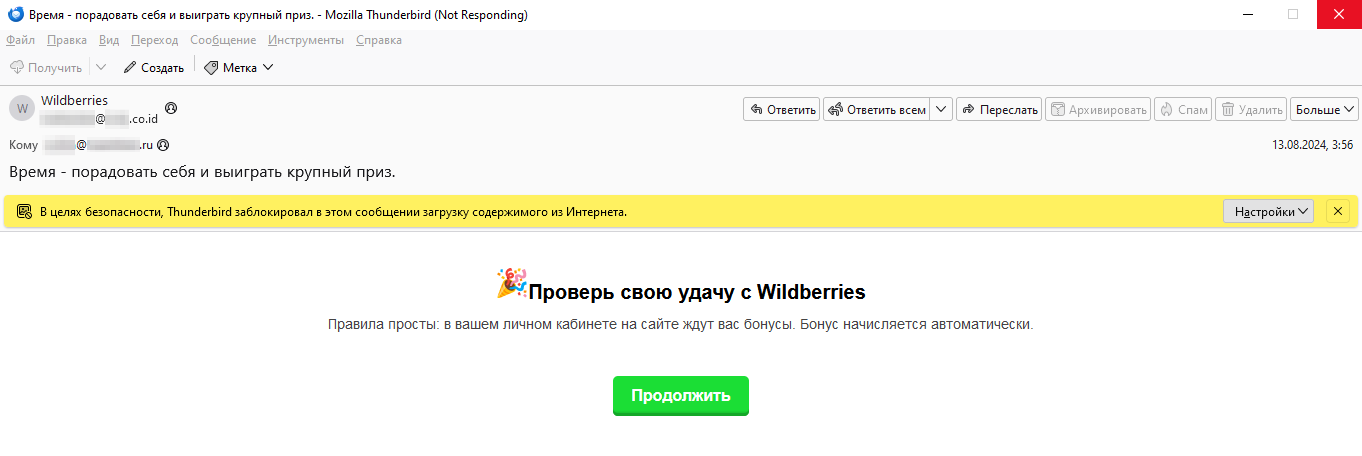

A fraudulent site, allegedly related to a Russian online store, offers the visitor the chance to participate in a nonexistent prize draw

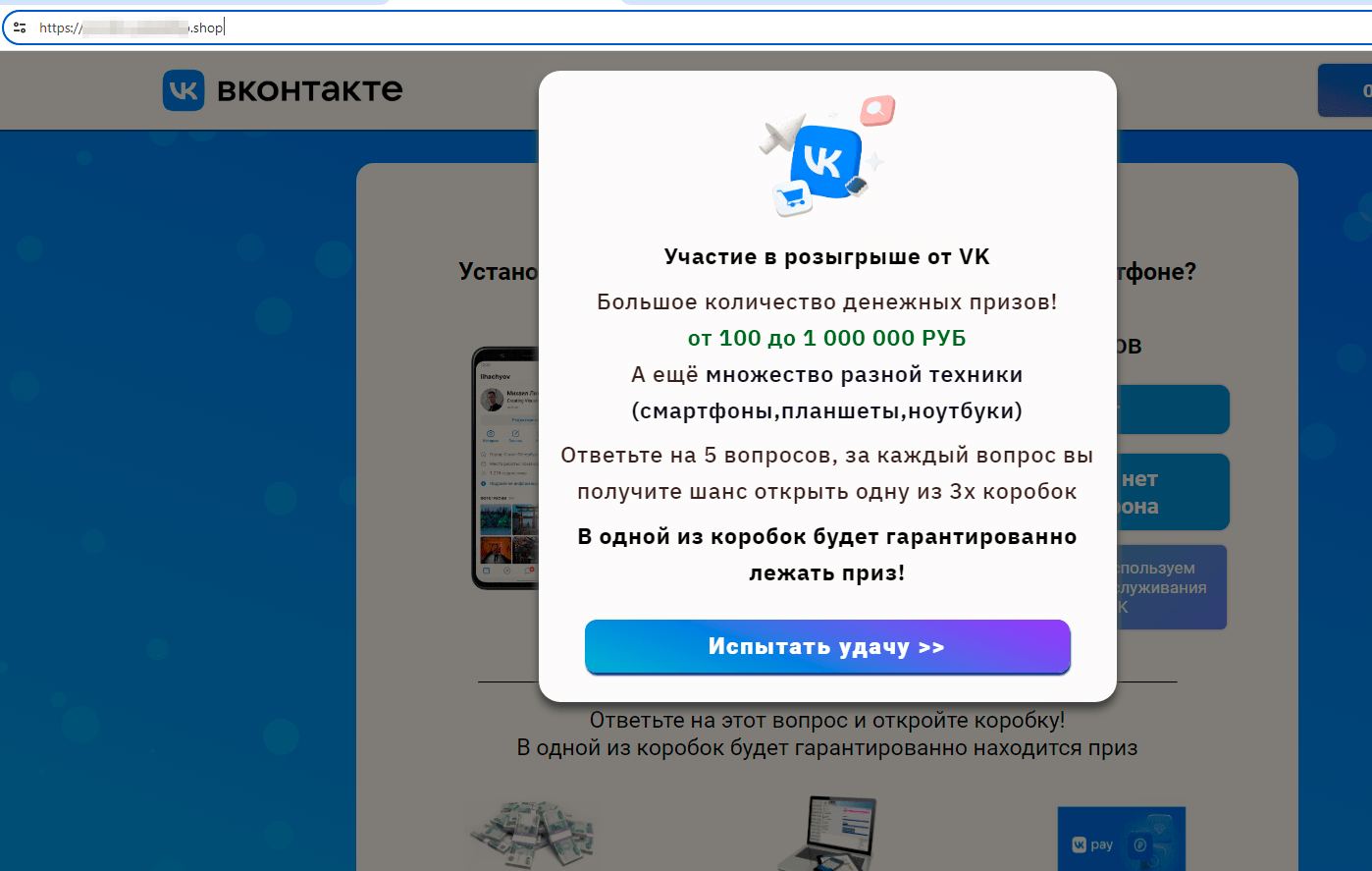

A fake social network website offers the chance to “try your luck” and win large cash prizes or other gifts

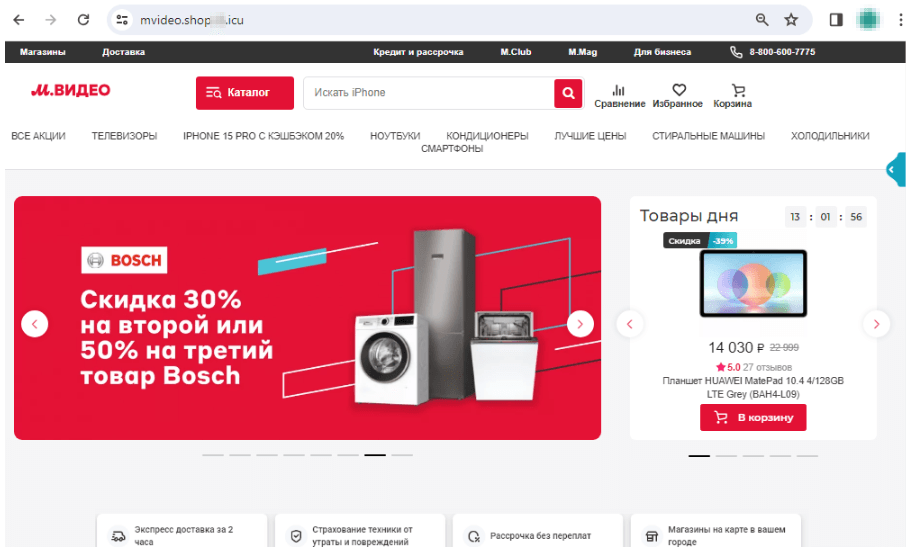

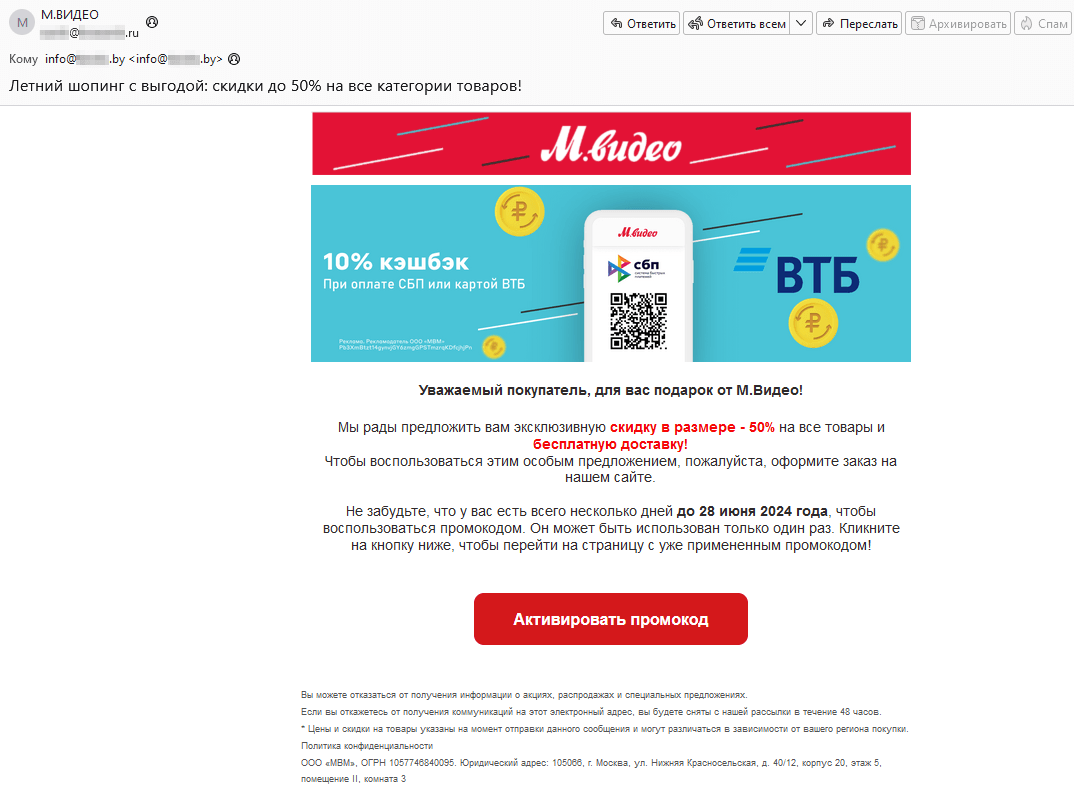

One of the current variants of such a scheme is not new: using fake websites of retailers and household appliance and electronics stores to offer users the opportunity to buy goods at a discount. On such sites, potential victims are typically asked to pay for their “orders” with a bank card. But last year, fraudsters started resorting to the Faster Payment System.

A fake website of a household appliance and electronics store promises potential victims big discounts

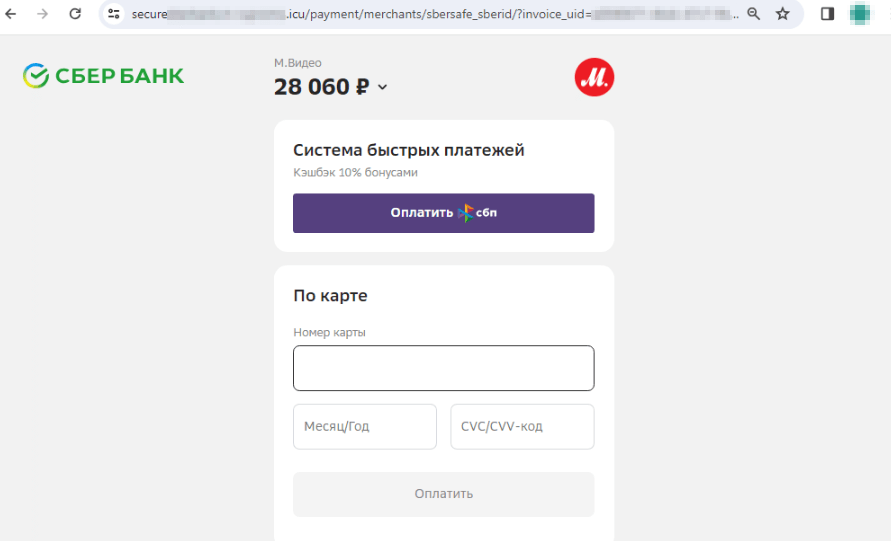

A fraudulent site offers visitors the option to use the Faster Payment System as one way to pay for their “order”

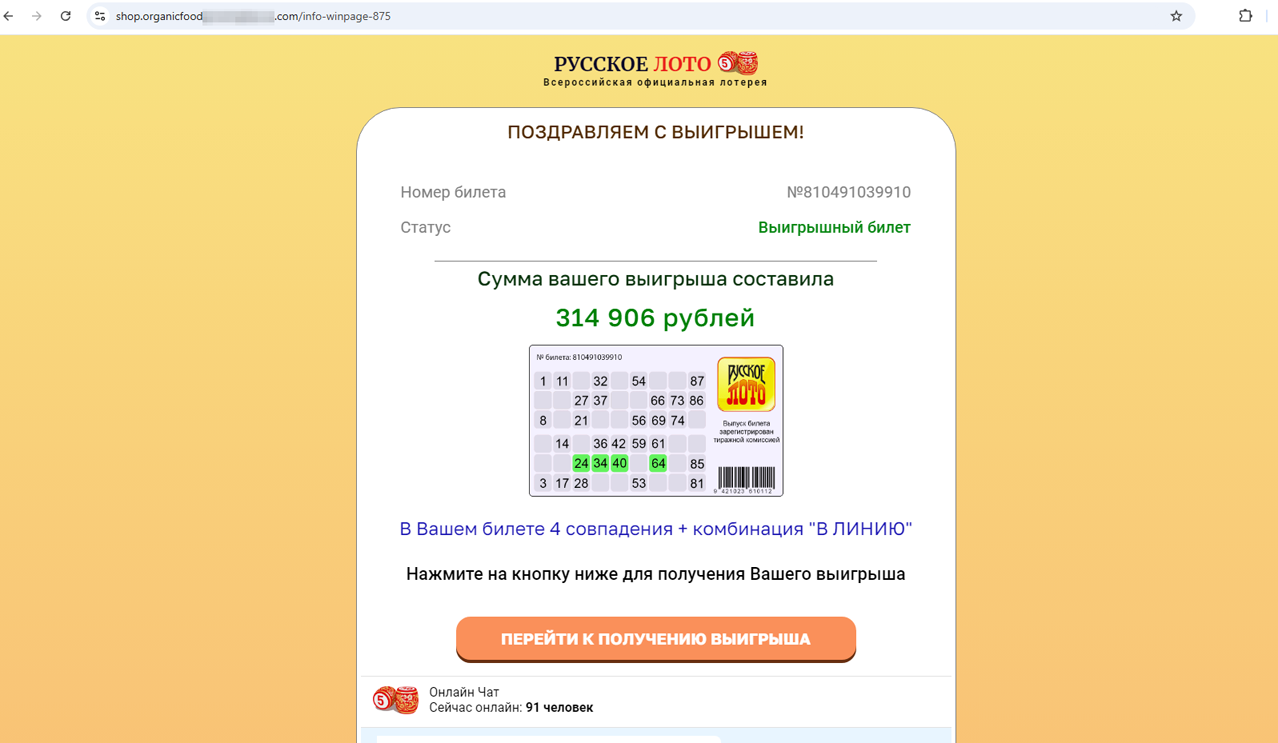

The scheme involving “free” lottery tickets also remained popular. Lottery draws, allegedly performed online, always end in “winnings” for potential victims. To get their prize, users also have to pay a “commission”.

This user has supposedly won 314,904 rubles in the lottery, and to “get” their prize, they need to pay a “commission”

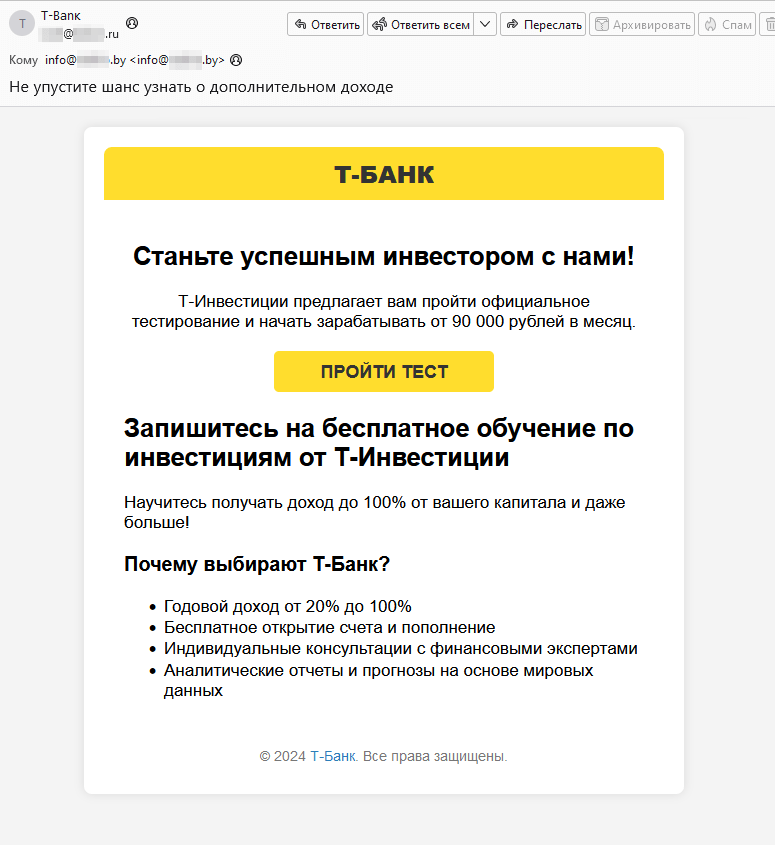

Scammers also kept fake finance-themed websites in their arsenal. Popular were such topics as receiving some payments from the government or private companies, investing in the oil and gas sector, financial literacy training, trading stocks with the help of “unique” automated systems or “verified” strategies that supposedly guarantee income, and others. Threat actors engaged in strategies that included exploiting the names of media personalities to attract users’ attention. Examples of such sites are shown below.

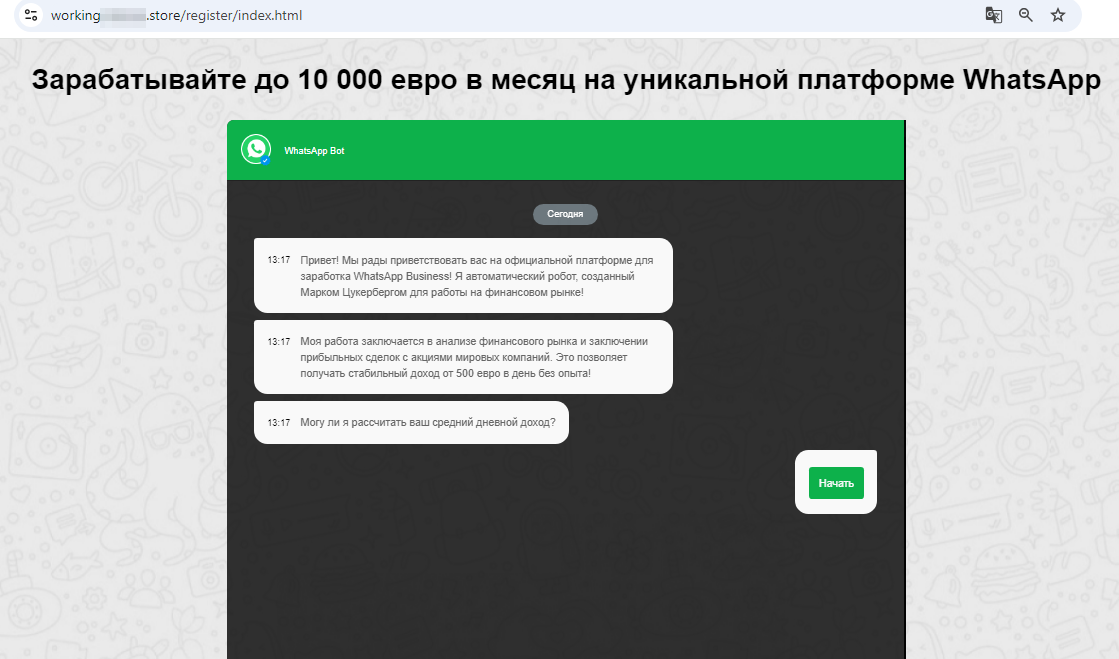

A fraudulent site offers visitors the chance to “make up to 10,000 euros per month on the unique WhatsApp platform”

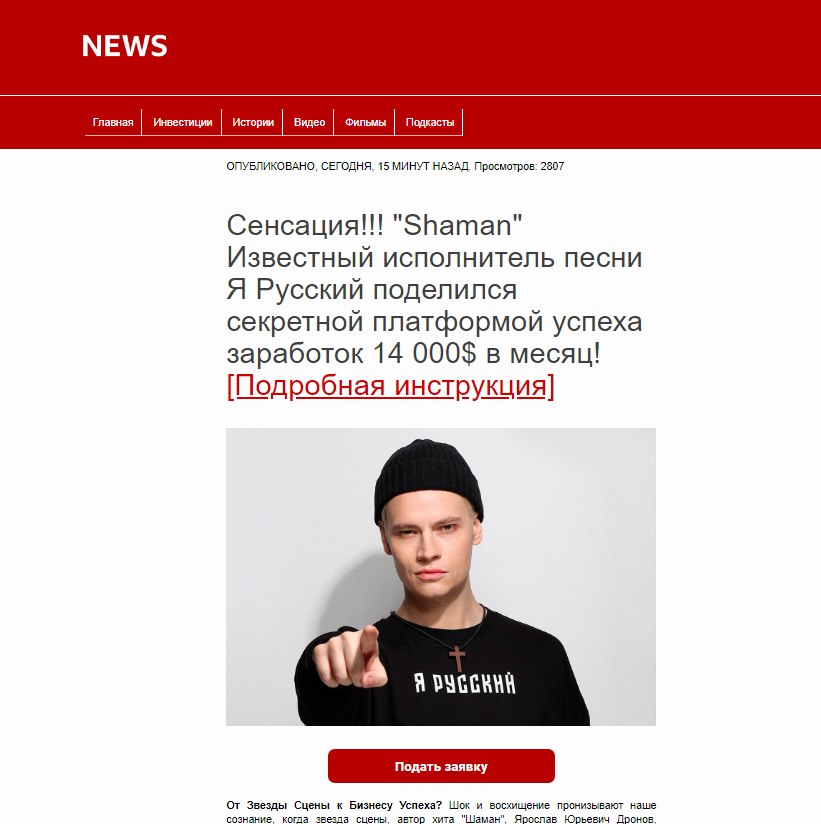

Russian singer Shaman “shared a secret platform for success” that allegedly can generate an income of $14,000 per month

The fake site of an oil and gas company offers access to an investment service and promises income starting at 150,000 rubles

Fraudulent sites that imitate real bank investing services

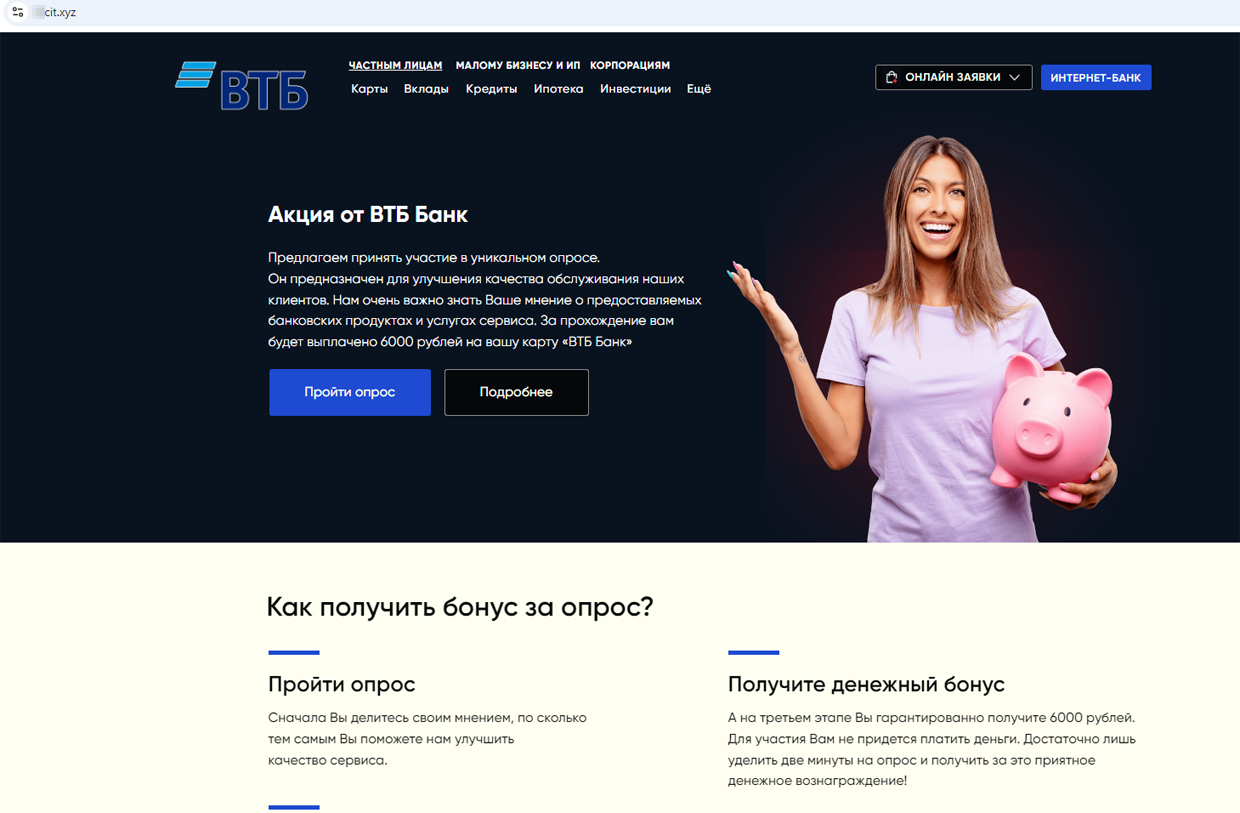

Meanwhile, our specialists detected new schemes. For example, scammers, allegedly on behalf of large companies, offered users a reward for participating in service-quality surveys. Such fakes included fictitious websites of credit organizations. On these, users were asked to provide sensitive personal information that could include their full name, the mobile phone number linked with their bank account, and their bank card number.

A fake bank website offers a reward of 6,000 rubles for participating in a survey on “improving service quality”

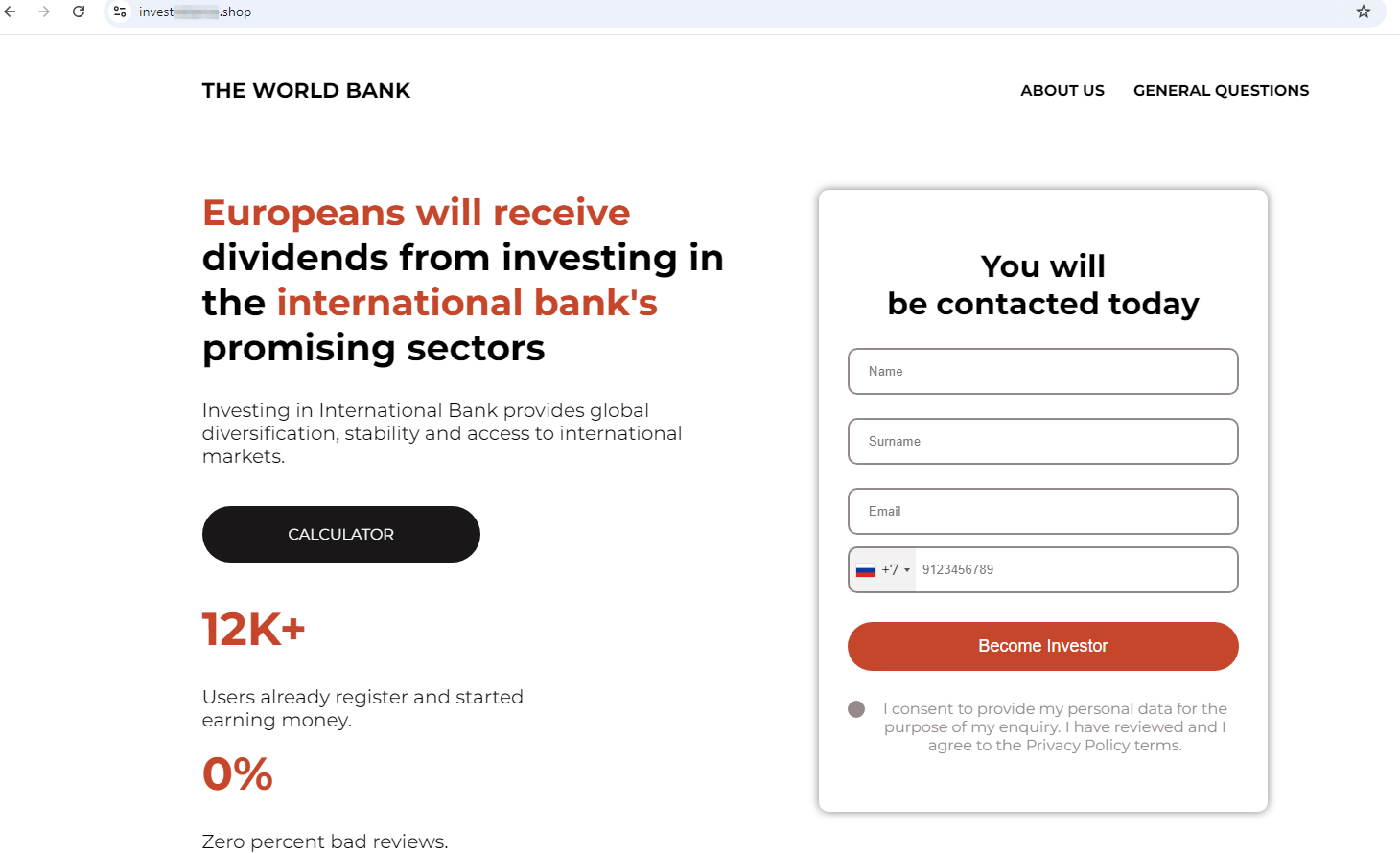

At the same time, such fakes also affected users in other countries. For instance, the site shown below assured European users that they will get dividends for investing in promising sectors of the economy:

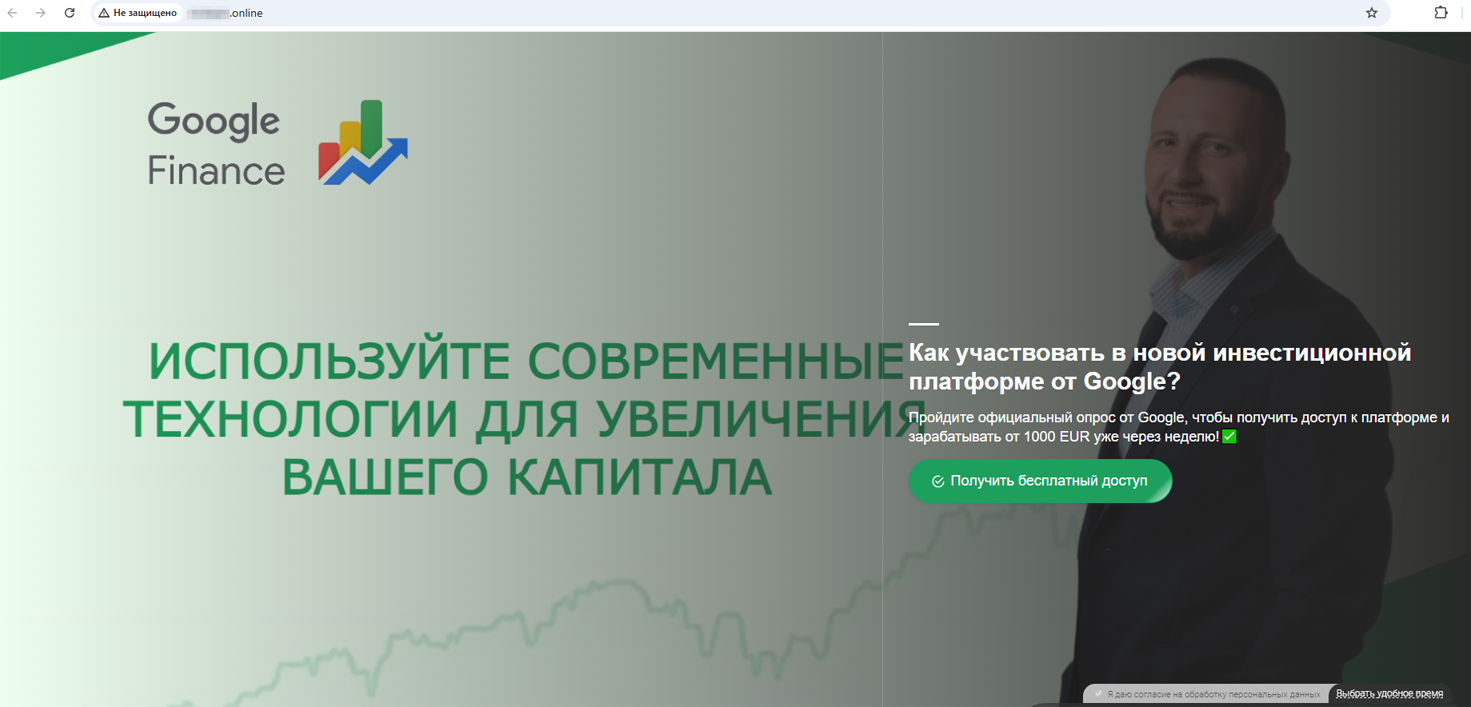

And this site advertised a “new investing platform from Google” that could allegedly help users make money, starting at €1000:

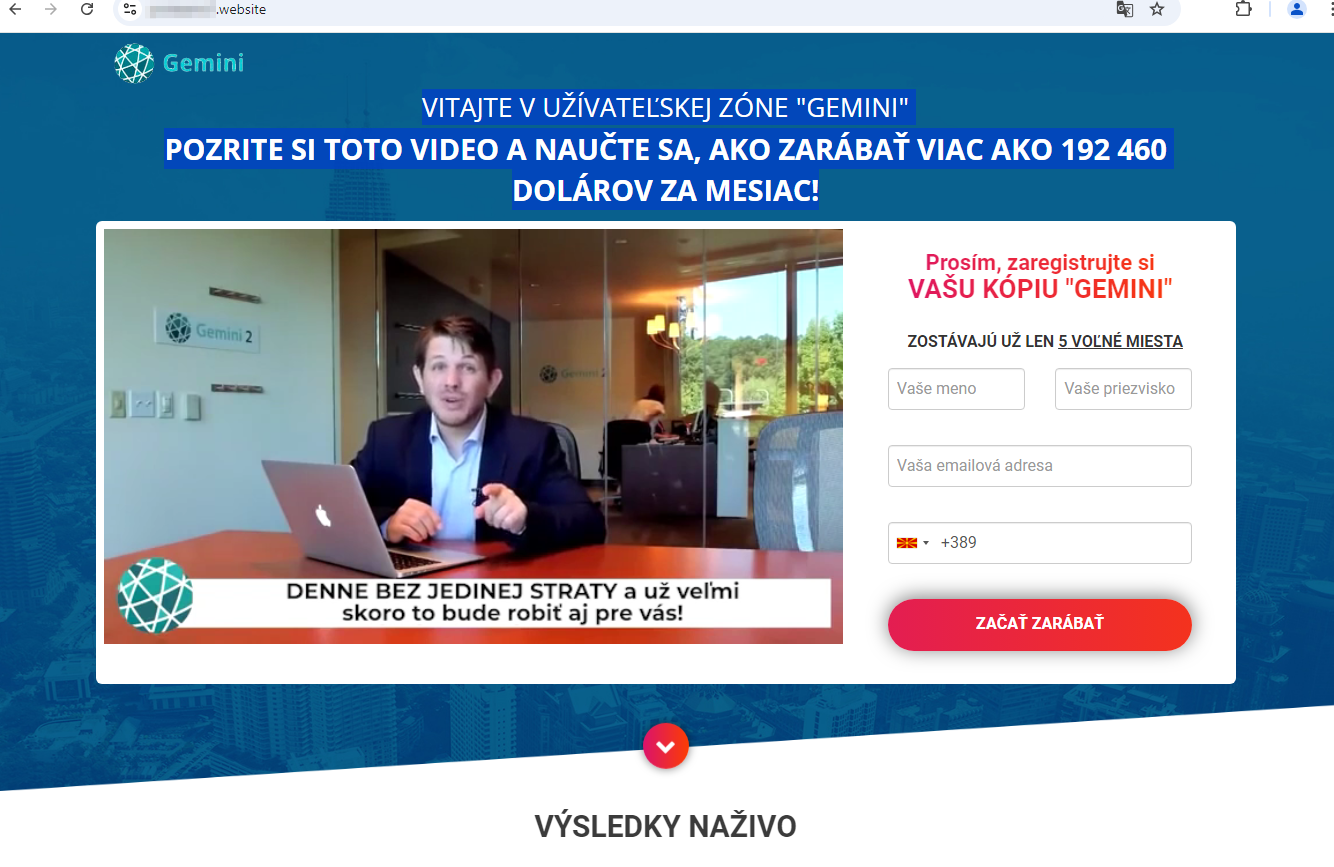

Another fraudulent Internet resource offered Slovak users the opportunity to “make more than $192,460 per month” with the help of some investing service:

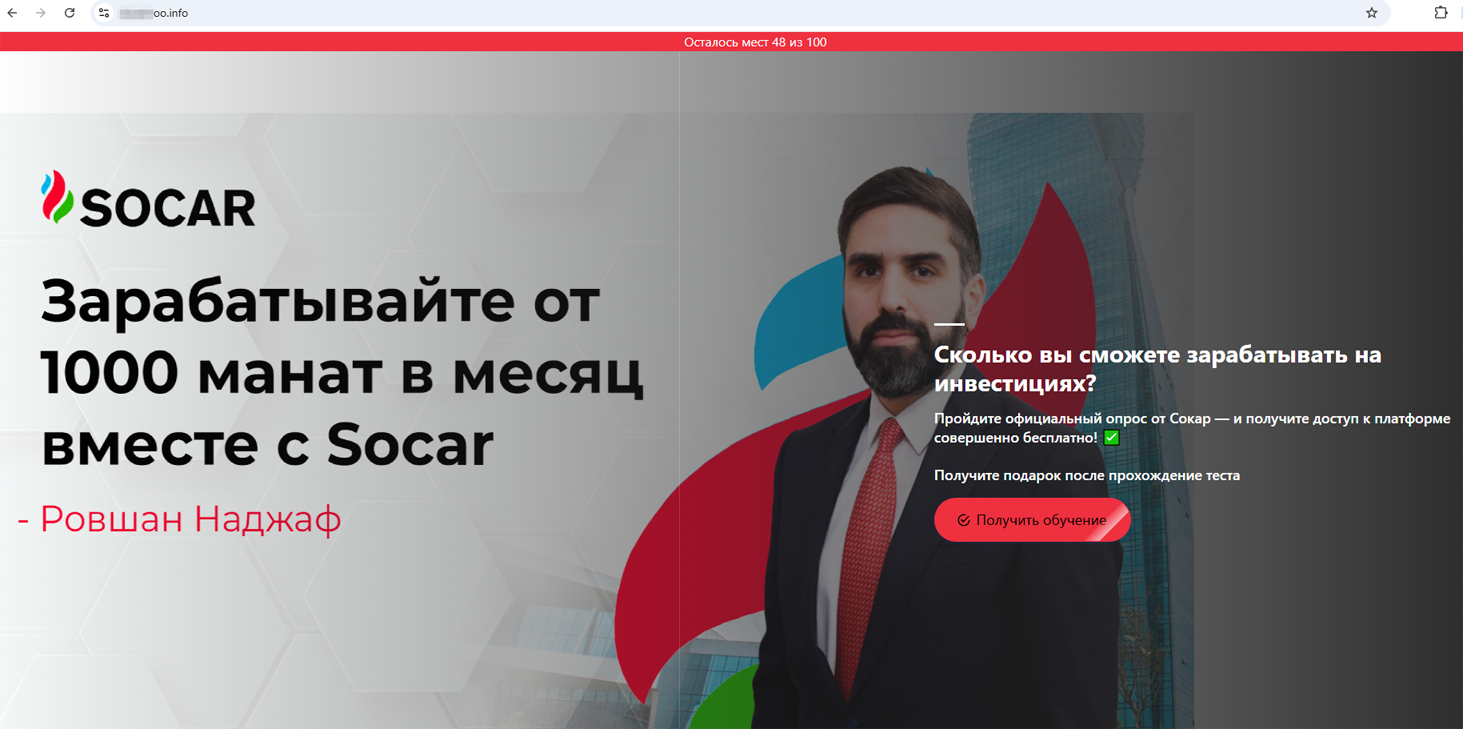

Users from Azerbaijan allegedly could also significantly improve their financial situation, making from 1000 manat per month. All they had to do was participate in a short survey and get access to the service, which was supposedly related to an Azerbaijani oil and gas company:

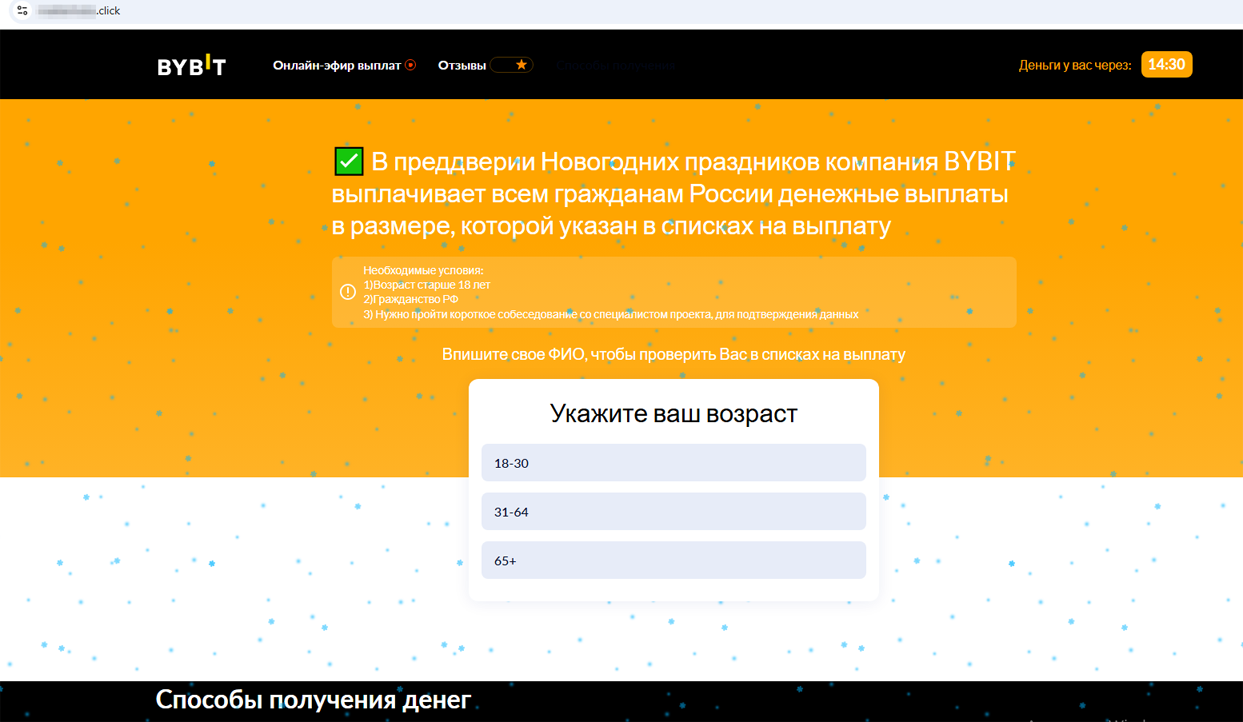

At the end of the year, fraudsters held to tradition and began adapting these fake websites to the New Year holiday theme. The next fake Internet resource of a crypto exchange, for example, promised Russian users New Year payments:

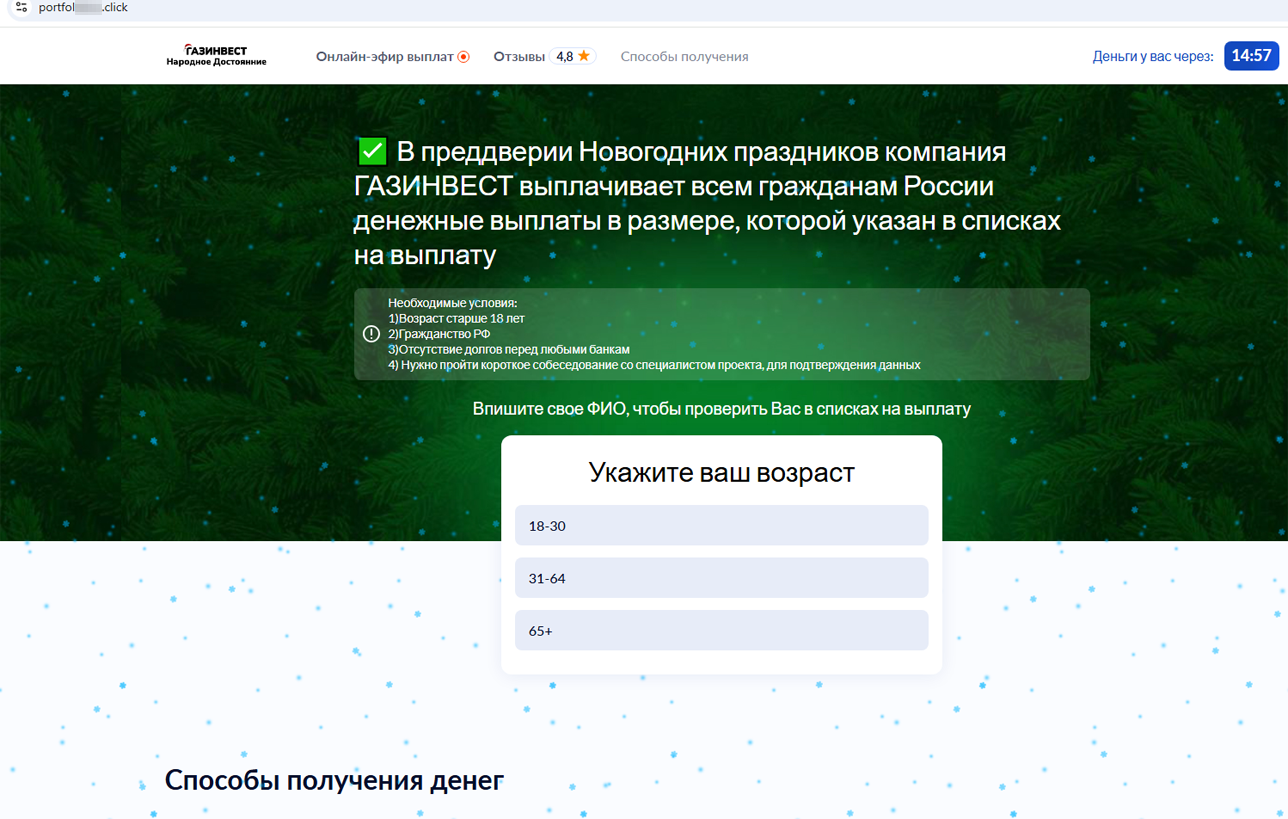

Another site offered users holiday payments supposedly on behalf of an investing company:

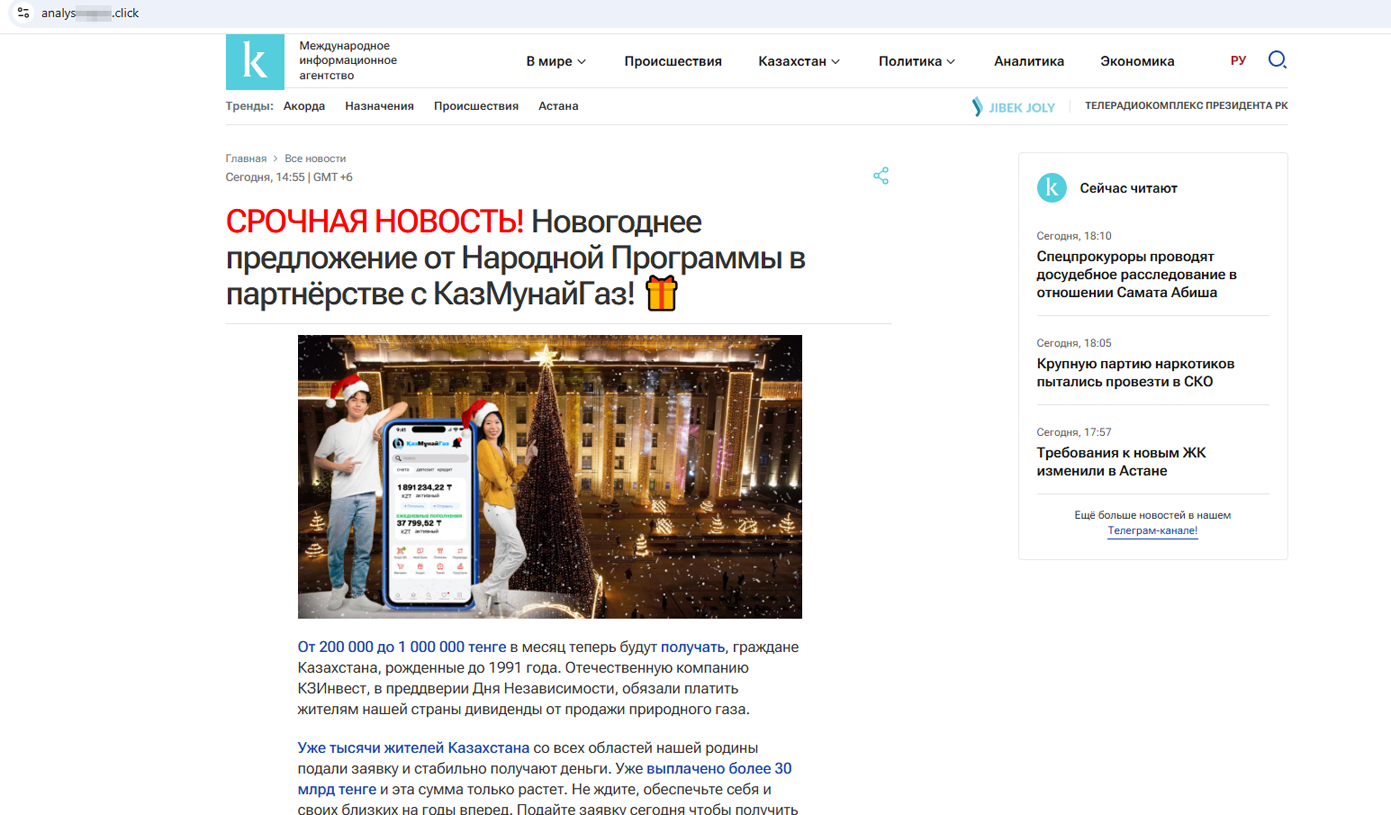

And this fraudulent Internet resource promised users from Kazakhstan large payments in honor of Independence Day as part of a “New Year offer”:

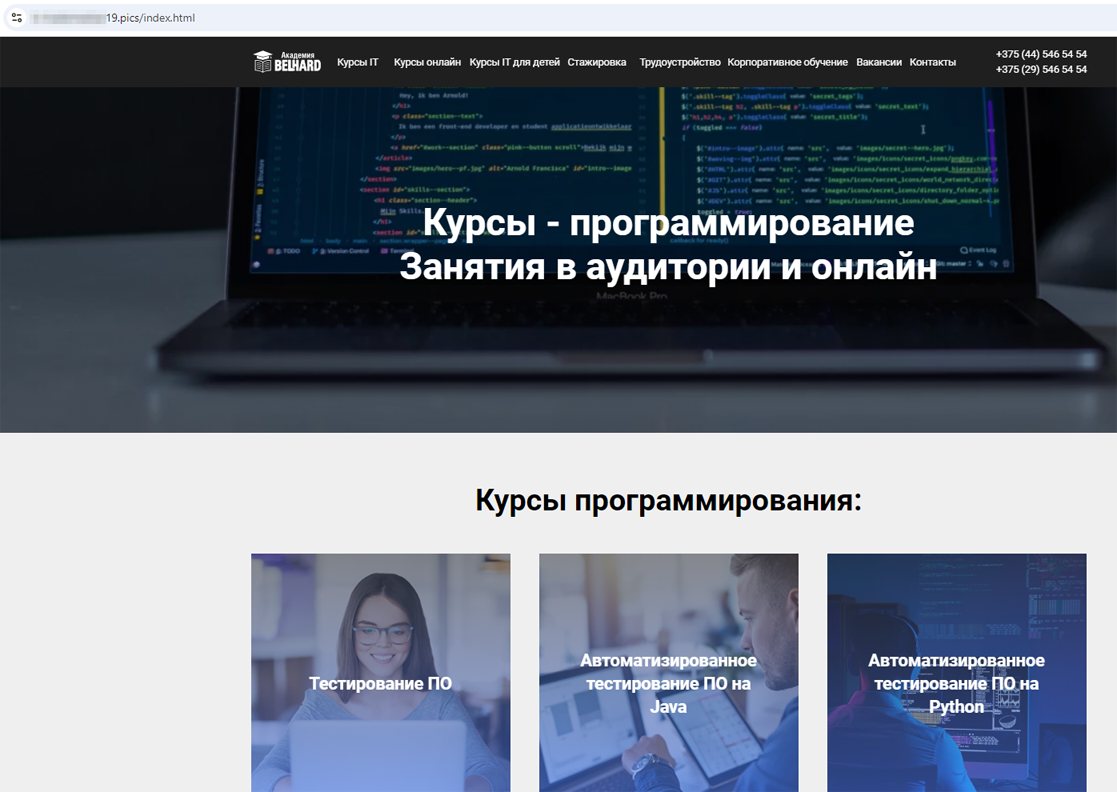

Throughout the year, our Internet analysts detected other phishing sites as well. Among them were fake websites of online education services. One, for instance, simulated the appearance of a genuine site and offered programming courses. To “receive a consultation”, users were asked to provide their personal data.

A fake website that was disguised as a real online resource of an online education service

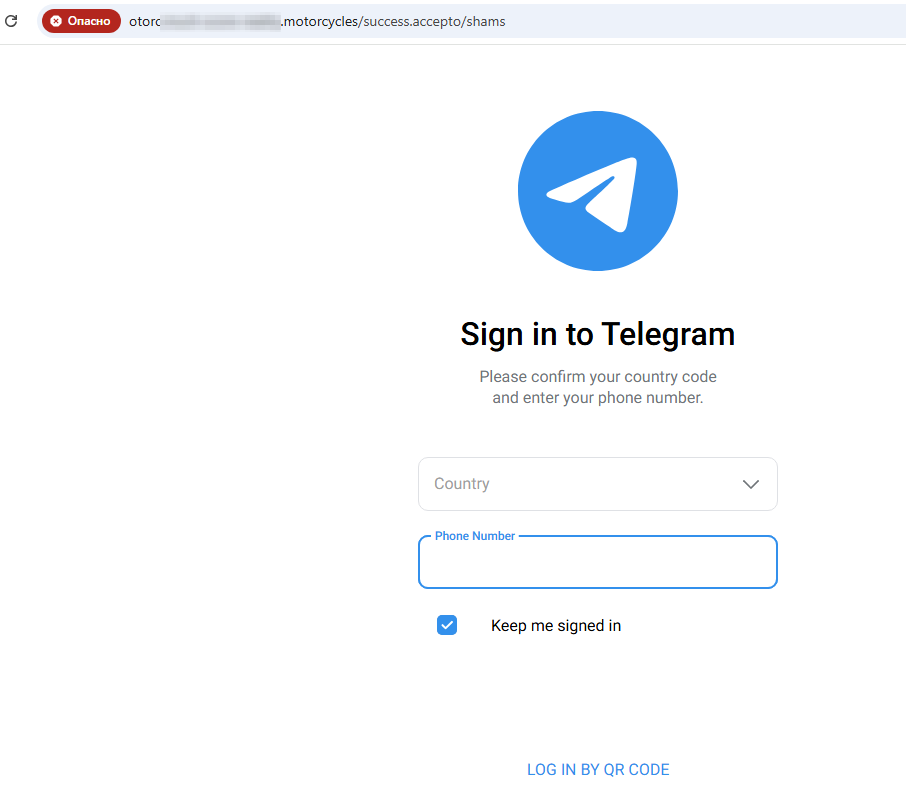

Additionally, attempts to steal Telegram user accounts continued. For this, fraudsters used phishing websites camouflaged as various online voting platforms. Among these, sites asking visitors to “vote in children’s drawing competitions” were widespread again. Potential victims are asked to provide their mobile phone number to receive a one-time code. However, when they enter this code on such a website, users are giving scammers access to their accounts.

A phishing website for “voting” in an online children’s drawing competition

On other similar sites, potential victims were offered a “free” subscription to a Telegram Premium service. Users are asked to log into their account, but the confidential data that they enter there is sent to the cybercriminals who then hijack their accounts. It is noteworthy that the links to these sites are distributed in a variety of ways, including through the messenger itself. And the real address of the target site in such messages often does not match the one that users see.

A phishing message in Telegram, in which, in order to “activate” a Telegram Premium subscription, users are asked to follow the given link. The text of this link does not in fact match the target URL

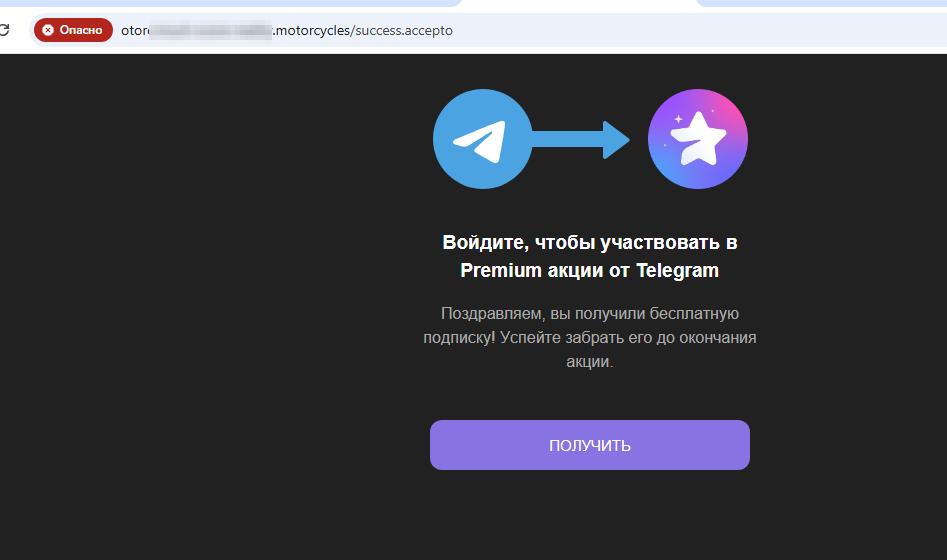

The phishing site loaded after the link in the fraudulent message is followed

After the user clicks the button on the previous page, the website displays an authorization form that looks like the genuine one

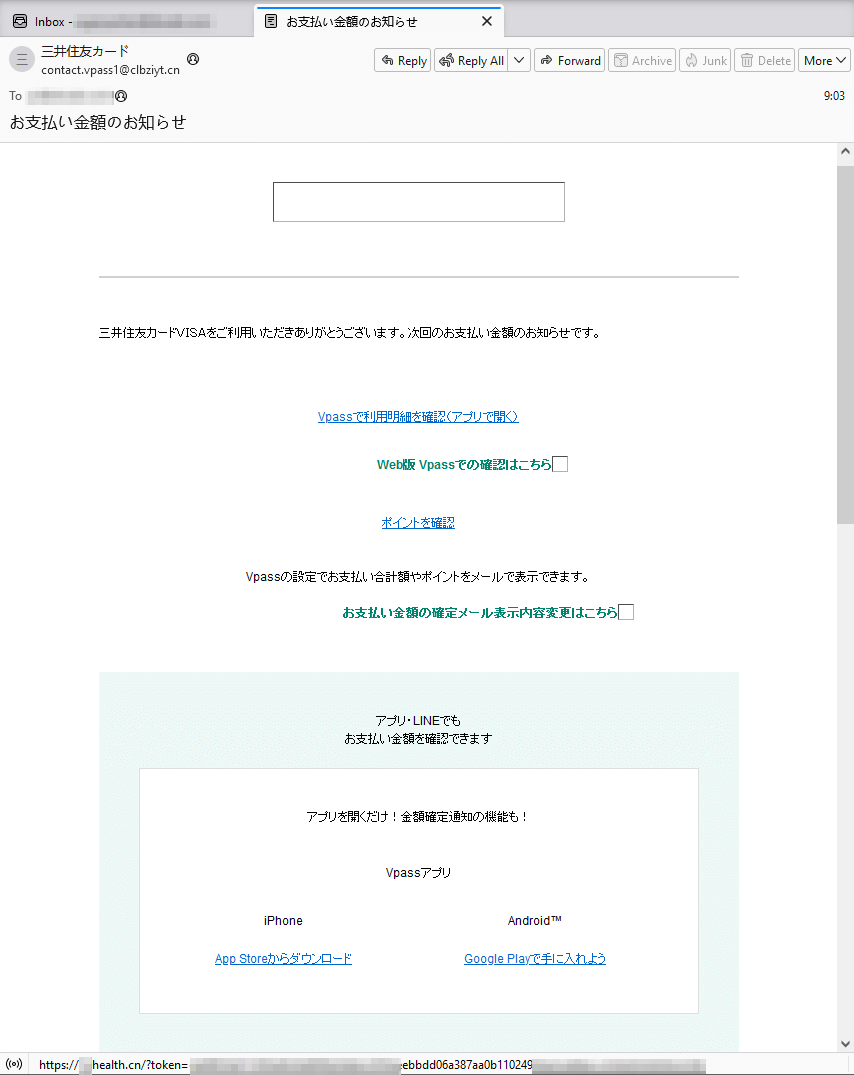

To distribute links to fraudulent sites, cybercriminals use email spam, among other avenues. Over the course of last year, our Internet analysts detected many different spam campaigns. They observed the active distribution of phishing emails targeting Japanese users. For example, scammers, allegedly on behalf of some bank, informed potential victims about some purchase and suggested that they view the details of the “payment” by following the provided link. In reality, this link led to a phishing Internet resource.

A phishing email, supposedly sent on behalf of a bank and offering Japanese users the option to view the details of a payment

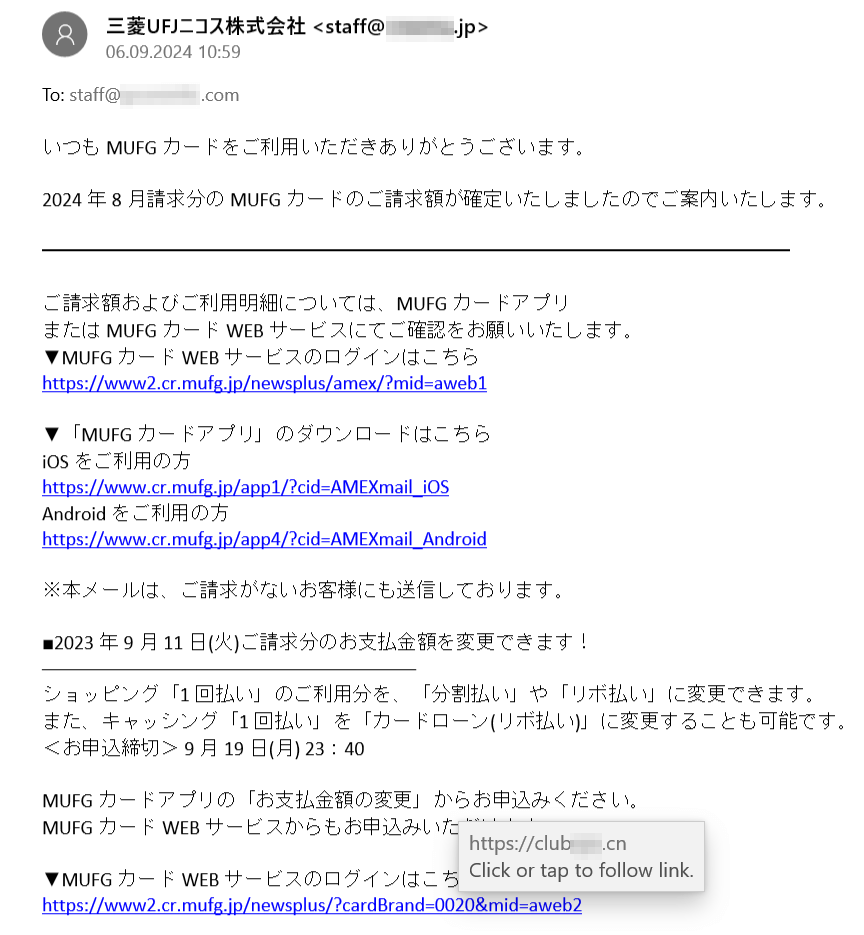

In another popular scenario, threat actors, supposedly on behalf of credit organizations, were sending fake notifications containing information about a month’s worth of bank card expenses. At the same time, the links to phishing sites were often concealed and seemed harmless in the email texts.

In the texts of spam emails, users saw the links to real bank web addresses, but when clicked, these addresses led to a fraudulent Internet resource

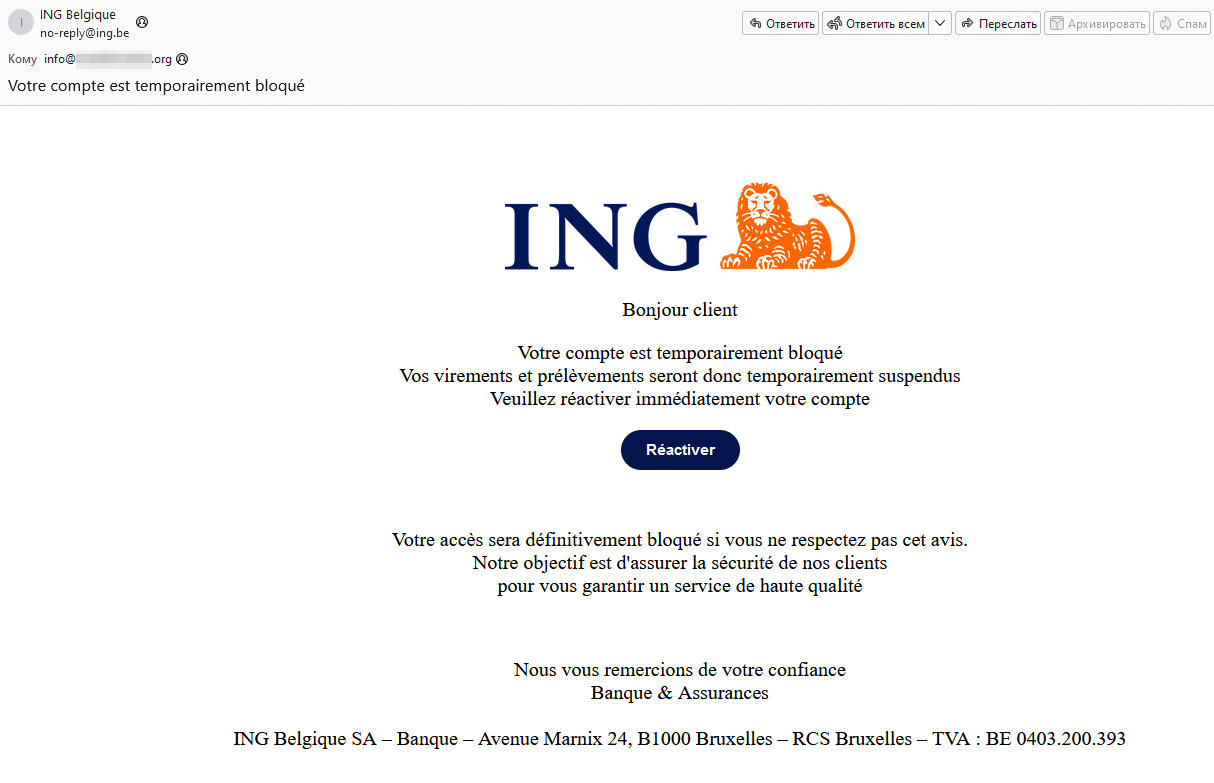

One spam campaign targeted European users. For example, users in Belgium encountered phishing emails that claimed their bank accounts had been “blocked”. To get them “unblocked”, they were asked to follow a link which, in fact, led to the fraudsters’ website.

An unwanted letter threatens a potential victim with a “blocked” bank account

We also detected other spam campaigns, for example, those aimed at an English-speaking audience. In one such campaign, potential victims received messages asking them to confirm receipt of a large money transfer. However, the link in these messages led to a phishing online bank authorization form, which resembled the one on the genuine bank’s website.

A spam email saying that the user supposedly needs to confirm receipt of $1,218.16 US

Russian users most often encountered spam letters that helped fraudsters lure potential victims to the phishing websites we covered earlier in this review. Common topics for these unwanted messages were prizes and discounts from online stores, free lottery tickets, and access to investment services. Examples of them are shown in the screenshots below.

A letter, allegedly from an online store, offering the chance to participate in a “prize draw”

A letter, allegedly from a credit organization, offering the chance to “become a successful investor”

A letter, allegedly sent on behalf of an electronics store, offering a promo code that the recipient can activate to get a discount on goods

Mobile devices

According to detection statistics collected by Dr.Web Security Space for mobile devices, in 2024, Android.HiddenAds trojans were once again the most common Android malicious programs. They accounted for more than a third of malware detections. Such trojans conceal their presence on infected devices and display ads. Among the most active members of this family were Android.HiddenAds.3956, Android.HiddenAds.3851, Android.HiddenAds.655.origin, and Android.HiddenAds.3994. At the same time, users encountered Android.HiddenAds.Aegis trojan variants capable of running automatically after installation. Other widespread malicious programs were Android.FakeApp trojans, used in a variety of fraudulent schemes, and Android.Spy spyware trojans.

The most active unwanted programs were members of the Program.FakeMoney, Program.CloudInject, and Program.FakeAntiVirus families. The first ones offer users the opportunity to get virtual rewards by completing various tasks and then withdraw those rewards as real money. However, users never receive any payments. The second ones are programs modified through a specialized cloud service. When modified, an uncontrolled code and a number of dangerous permissions are added to them. The third ones are programs that imitate anti-virus software, detect nonexistent threats and offer users the option to buy the full version to fix the “problems” that had allegedly been found.

Tool.SilentInstaller utilities, which allow Android apps to run without being installed, were once again the most commonly detected potentially dangerous software. They accounted for more than a third of the detections of this type of threat. Also widespread were apps modified with the NP Manager tool (these are detected as Tool.NPMod). A special module is embedded into such modified programs, which allows them to bypass the digital signature verification process once they have been modified. Apps protected with the Tool.Packer.1.origin software packer were also detected quite often, as was the Tool.Androlua.1.origin framework. The latter allows installed Android programs to be modified and potentially dangerous Lua scripts to be executed.

The most widespread adware software was the new family Adware.ModAd, which accounted for almost half of all detections. These are specially modified versions of the WhatsApp messenger, whose functions have been injected with a specific code for loading advertising links. Members of the Adware.Adpush family ranked second, while another new family, Adware.Basement, occupied third place.

In 2024, Android banking trojans were slightly more active than in 2023. At the same time, our specialists observed an increase in the popularity of some techniques used to protect malware from analysis and detection. This was commonly seen in banking trojans. Such techniques included undertaking various manipulations with the ZIP file format (as Android APK files are based on this format) and the configuration file AndroidManifest.xml of Android apps.

The widespread distribution of the Android.SpyMax malicious program is worth a separate mention. Cybercriminals actively used this spyware trojan as a banking trojan, particularly against Russian users (46.23% of detections), and also against Brazilian (35.46% of detections) and Turkish (5.80% of detections) Android device owners.

Throughout the year, Doctor Web’s virus analysts detected over 200 different threats on Google Play. Among them were trojans that subscribe users to paid services, spyware trojans, and fraudulent and adware apps. Combined, they have been downloaded at least 26.7 million times. Moreover, our specialists detected another attack on Android TV box sets: the Android.Vo1d backdoor has infected almost 1.3 million user devices in 197 countries. This trojan placed its components into the system storage area and, when commanded, could covertly download third-party apps from the Internet and install them.

To find out more about the security-threat landscape for mobile devices in 2024, read our special overview.

Prospects and possible trends

The events of the past year have once again demonstrated the diversity of the modern cyber-threat landscape. Malicious actors are interested in both large targets, like private corporate and government sector, and ordinary users. The functionality of many of the malicious programs used in the targeted attacks we investigated indicates that virus writers are constantly searching for new opportunities to improve their methods of conducting malicious campaigns and developing their tools. Over time, new techniques inevitably transfer to more widespread threats. In this regard, in 2025, we may witness the emergence of more trojans that use eBPF technology to conceal their malicious activity. Moreover, we should also expect new targeted attacks, including those that utilize exploits.

One of the main goals of cybercriminals is to make money illegally, so 2025 may see an increase in the activity of banking and ad-displaying trojans. In addition, users may be threatened by more malware with spyware functionality.

At the same time, not only Windows computer users will be the target, but also users of other operating systems, such as Linux and macOS. The distribution of mobile threats will continue. Android device owners should above all be wary of the emergence of new spyware and banking trojans as well as malicious and unwanted ad-displaying apps. New attempts to infect Android TVs, Android TV box sets, and other Android-based devices are also to be expected. Moreover, chances are high that new threats will emerge on Google Play.