Doctor Web’s mobile malware review for 2019

February 11, 2020

Overview

In the past year, trends towards multicomponent threats for Android devices persisted. Virus writers increasingly transfer the main functions of trojans to separate modules that are downloaded and launched after malicious applications have been installed. This not only helps the trojans avoid detection, but also allows cybercriminals to create universal malware that can perform a vast range of tasks.

Google Play continued serving as a source of various threats. Despite Google’s efforts to protect the official Android app store, cybercriminals still manage to use it to distribute malicious, unwanted, and other dangerous software.

Clicker trojans were highly active and raked in a lot of money for cybercriminals by ensuring automatic clicks on links and banners, as well as by subscribing victims to expensive mobile services. We also detected new trojan adware, as well as unwanted adware modules that display aggressive ads and interfere with the normal operation of Android devices. Trojans that download and try to install other malicious applications, as well as unwanted software, were also frequently seen in the past year.

Throughout 2019, users continued facing typical Android bankers. Android users were also threatened by spyware and all kinds of backdoors, i.e. trojans that allow cybercriminals to control the infected devices and perform various actions on command.

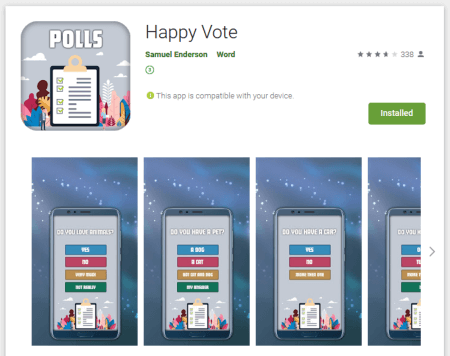

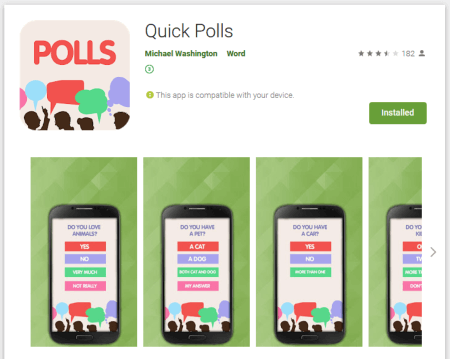

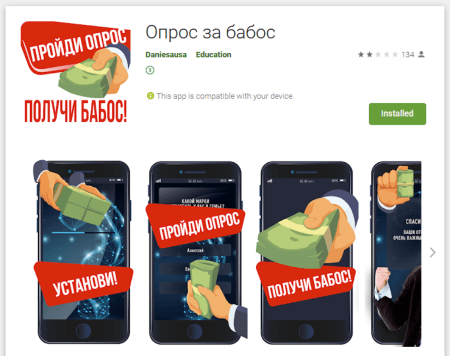

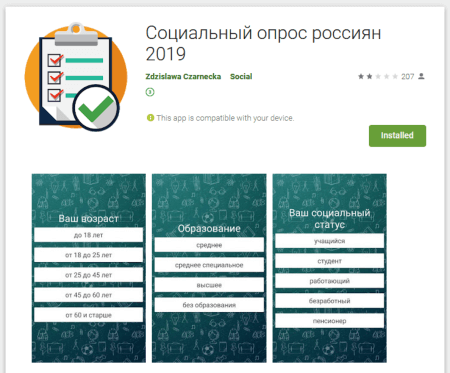

Issues with fraud also remained relevant. Almost every month, Doctor Web specialists detected new applications designed to deceive and steal money from Android device users. One of the most popular schemes used by cybercriminals involved websites with fake polls offering so-called ‘rewards’ to potential victims.

New malicious applications that exploit critical Android vulnerabilities were also detected.

Trends of the past year

- Rapid distribution of threats on Google Play.

- The activity of new banking trojans.

- New malware that helps cybercriminals steal money from Android users.

- The rising number of modular trojans that avoid being detected for a longer time.

- New vulnerabilities and malware that exploits them.

Most notable events of 2019

In February, Doctor Web virus analysts detected several dozens of adware trojans of the Android.HiddenAds family on Google Play. Cybercriminals disguised them as camera applications, image and video editors, useful utilities, desktop wallpaper collections, games, and other harmless software. Upon installation, the trojans hid their icons from the home screen by replacing them with shortcuts. Users were able to remove the shortcuts, thinking they had removed the trojans; but in fact, they continued working silently and constantly generated and displayed annoying ads.

In attempts to spread the trojans more successfully, cybercriminals advertised them on popular online services, such as Instagram and YouTube. As a result, nearly 10 million users downloaded the malware. Throughout the year, attackers actively used this method to spread other trojans of this family.

In March, virus analysts discovered a hidden function that enabled downloading and running of unverified modules in the popular UC Browser and UC Browser Mini. This software could download additional plugins, bypassing Google Play, and thereby rendering over 500 million users vulnerable to potential attacks.

In April, Doctor Web published a study on the dangerous Android.InfectionAds.1 trojan, which exploited the critical Android vulnerabilities Janus (CVE-2017-13156) and EvilParcel (CVE-2017-13315) to infect and automatically install other applications. Virus writers distributed Android.InfectionAds.1 via third-party application stores, and several thousand Android device users managed to download it from there. The main function of this trojan was to display advertising banners and replace popular advertising platform identifiers in such a way that all profits from legal advertising in the infected applications was funnelled to the authors of Android.InfectionAds.1 instead of the actual app developers.

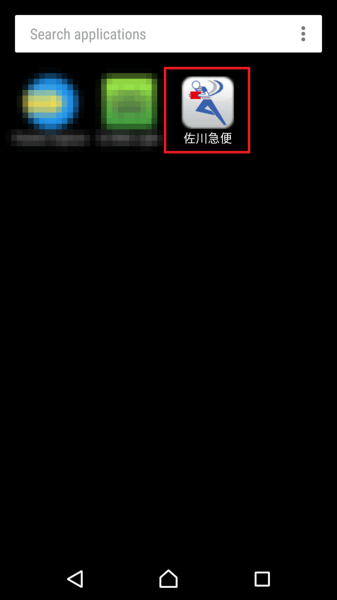

The same month, our virus analysts discovered a modification of the banker, Android.Banker.180.origin, which targeted Japanese users. The trojan was spread as an application for mail tracking and concealed its icon after launch.

Virus writers controlled the banker using the specifically created VKontakte pages, where the address of one of the command and control servers was encrypted in the Activities field. Android.Banker.180.origin searched for this field using a regular expresssion, decrypted the address, and connected to the server, waiting for further commands.

The trojan hooked and sent SMS text messages, showed phishing windows, made phone calls, and listened to the environment using the microphone of an infected device at the command of cybercriminals. It could also control the infected devices. For example, it could independently turn on the Wi-Fi module, establish an Internet connection via the mobile network, and block the screen.

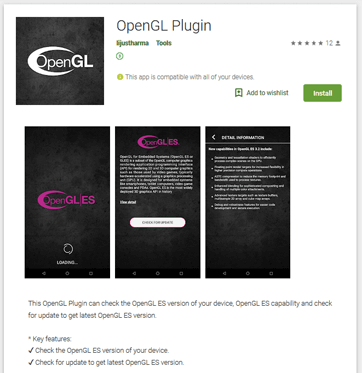

In July, virus analysts discovered and investigated the dangerous backdoor, Android.Backdoor.736.origin, distributed via Google Play under the guise of software for updating the OpenGL ES interface. This trojan, also known as PWNDROID1, executed cybercriminals’ commands and spied on users. For instance, it collected information about the location of devices, phone calls, contact list, and sent files stored on devices to the server. It could also download and install applications and display phishing windows to steal usernames, passwords, and other sensitive data.

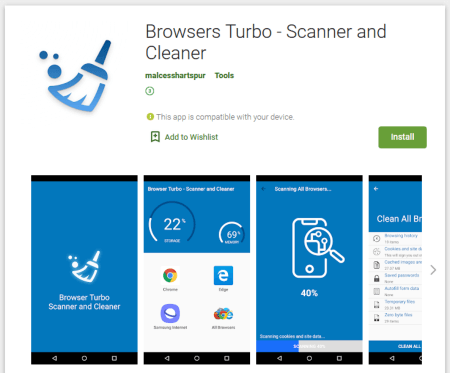

Our experts uncovered a new modification of this backdoor as early as November. It was also distributed via the official Android application store; but this time, the cybercriminals made the trojan look like a utility for configuring and speeding up the browser.

At the end of the summer, Doctor Web virus analysts detected the clicker trojan, Android.Click.312.origin, which was downloaded by some 102 million users. The clicker was built into a wide variety of applications, such as audio players, dictionaries, barcode scanners, online maps, and others — a total of more than 30 apps. At the command of the command and control server, Android.Click.312.origin opened websites with advertising and other dubious content.

In autumn, our specialists detected other trojans of the Android.Click family: Android.Click.322.origin, Android.Click.323.origin, and Android.Click.324.origin. They opened advertising websites and also subscribed the victims to expensive mobile services. These trojans were selective and only performed their malicious functions on the devices of users from certain countries. The software the clickers were built in was secured by a special packer, and the trojans pretended to be well-known advertising and analytical platforms to hinder their detection.

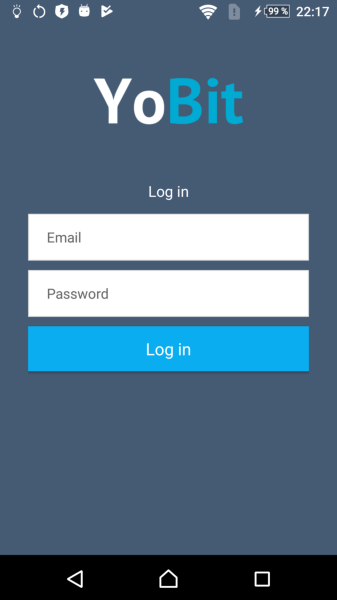

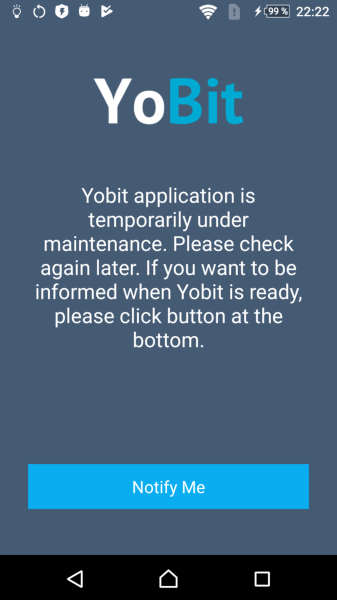

In October, we found the banking trojan Android.Banker.352.origin on Google Play. It was distributed under the guise of the official YoBit crypto exchange application. At startup, it displayed a fake login window and stole the credentials of exchange clients that they entered. The banker then showed a message about the service being temporarily unavailable.

Android.Banker.352.origin hooked two-factor authentication codes from text messages, as well as access codes from emails. It also hooked and blocked notifications from various instant messengers and email clients. All stolen data was stored in the Firebase Database.

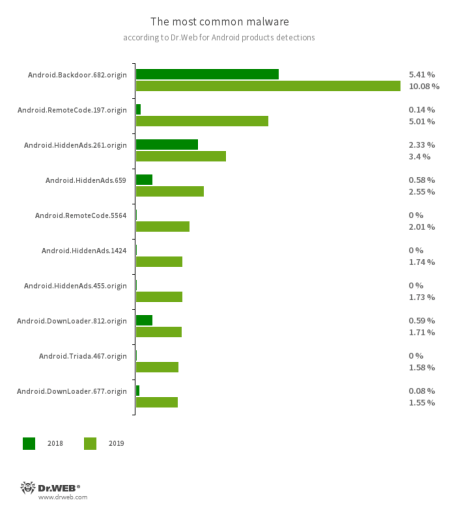

The activity of the Android.RemoteCode trojan family grew in the past year. These malicious applications downloaded additional modules and arbitrary code and then launched them upon the command of the attackers. Compared to 2018, they were detected on user devices 5.31% more often.

In September, we learned about the new trojan family Android.Joker. These malware, too, could download and run arbitrary code. They could also open websites and signed victims up for paid services. These trojans were most commonly spreading under the guise of camera applications, photo and video editors, instant messengers, games, image collections, and useful utilities that allegedly optimised the operation of Android devices. Over the course of several months, Doctor Web virus analysts identified numerous modifications of these malicious applications.

Statistics

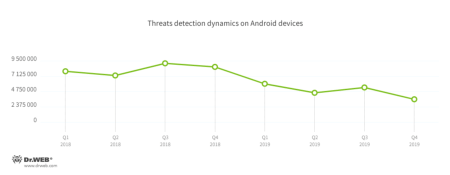

In 2019, Dr.Web For Android detected 19,367,317 threats on users' devices, which is 40.9% less than the prior year. In January, the spread of trojans, unwanted and potentially dangerous software, as well as adware peaked. By mid-summer, their activity decreased, but then increased again in July and August. The number of detections then began to lower again and dropped to a minimum in December.

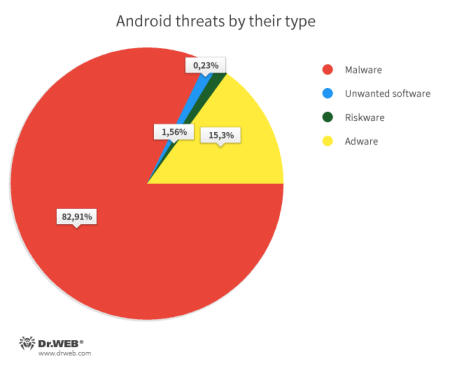

The vast majority of threats were different varieties of trojans. Adware applications and plugins landed in second place. The third and fourth places were secured by riskware and unwanted software, which lagged far behind the first two places.

According to detection statistics, the most common malware were adware trojans and trojans that downloaded, launched, or installed other malicious applications, as well as executed arbitrary code. Backdoors were also widespread, allowing cybercriminals to remotely control infected devices and spy on users.

- Android.Backdoor.682.origin

- A backdoor that executes cybercriminals’ commands and helps them control infected mobile devices.

- Android.RemoteCode.197.origin

- Android.RemoteCode.5564

- Trojans that download and execute arbitrary code. They are distributed under the guise of games and useful applications.

- Android.HiddenAds.261.origin

- Android.HiddenAds.659

- Android.HiddenAds.1424

- Android.HiddenAds.455.origin

- Trojans that display obnoxious advertising. To complicate their removal, they hide their icom from the Android home screen.

- Android.Triada.467.origin

- A multi-functional trojan that performs various malicious actions.

- Android.DownLoader.677.origin

- A downloader trojan that downloads other malware on Android devices.

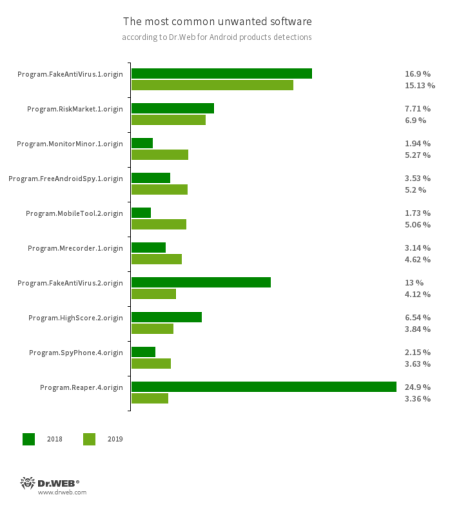

One of the most common unwanted applications were trackers and monitoring software. Such software silently collects confidential information, such as SMS message history, data about phone conversations, messages from social media, device location, browser history, files stored on devices, etc., and can be used for cyber spying.

Users were also targeted by antivirus-simulating software, as well as questionable application stores, where cybercriminals could spread trojans and sell pirated copies of free software for profit.

- Program.FakeAntiVirus.1.origin

- Program.FakeAntiVirus.2.origin

- Detects adware that imitates anti-virus software.

- Program.MonitorMinor1.origin

- Program.MobileTool.2.origin

- Program.FreeAndroidSpy.1.origin

- Program.MobileTool.2.origin

- Program.SpyPhone.4.origin

- Spyware that monitors activities of Android users and may serve as a tool for cyber espionage.

- Program.RiskMarket.1.origin

- An app store that contains trojan software and recommends that users install it.

- Program.HighScore.2.origin

- An app store that invites users to install free Google Play apps by paying for them via expensive text messages.

- Program.Reaper.4.origin

- This software is pre-installed on some Android smartphone models. It silently collects and transfers data about the devices and their location to a remote server.

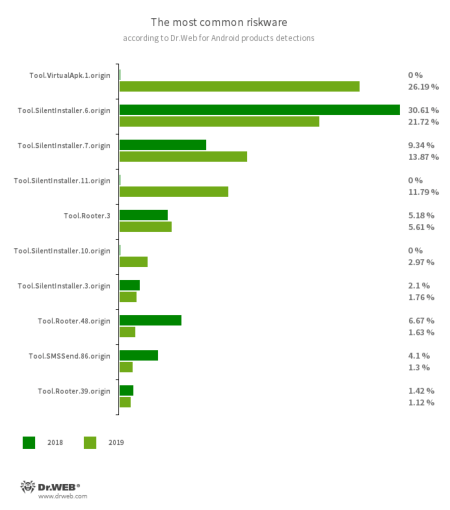

The most frequently detected riskware were utilities that allow to run software without first installing it, as well as software that helped obtain root privileges.

- Tool.VirtualApk.1.origin

- Tool.SilentInstaller.6.origin

- Tool.SilentInstaller.7.origin

- Tool.SilentInstaller.11.origin

- Tool.SilentInstaller.10.origin

- Tool.SilentInstaller.3.origin

- A riskware platform that allows applications to launch APK files without installing them.

- Tool.Rooter.3

- Tool.Rooter.48.origin

- Tool.Rooter.39.origin

- Utilities designed to obtain root privileges on Android devices. They may be used by cybercriminals and malware.

- Tool.SMSSend.86.origin

- A bulk messaging application.

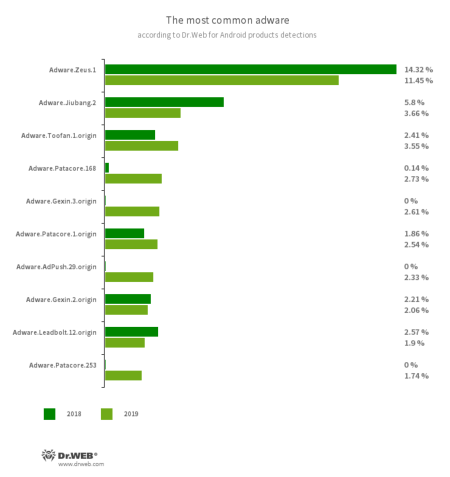

The most widely used adware were software modules that display banners and video ads over the interface of other apps and the operating system. They interfered with the normal work of Android devices and could lead to significant expenses if a user had a limited Internet service plan.

- Adware.Zeus.1

- Adware.Jiubang.2

- Adware.Toofan.1.origin

- Adware.Patacore.168

- Adware.Gexin.3.origin

- Adware.Patacore.1.origin

- Adware.AdPush.29.origin

- Adware.Gexin.2.origin

- Adware.Leadbolt.12.origin

- Adware.Patacore.253

- Ad modules embedded by software developers into applications to siphon money from them. Such modules display annoying notifications with ads, banners, and video commercials that interfere with the normal operation of the devices. They can also collect sensitive information and transmit it to a remote server.

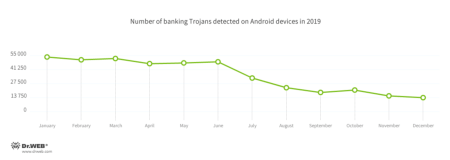

Banking trojans

According to the detection statistics of Dr.Web for Android, banking trojans were detected on Android devices over 428,000 times over the past 12 months. The spread peaked in the first half of the year, and then activity gradually decreased.

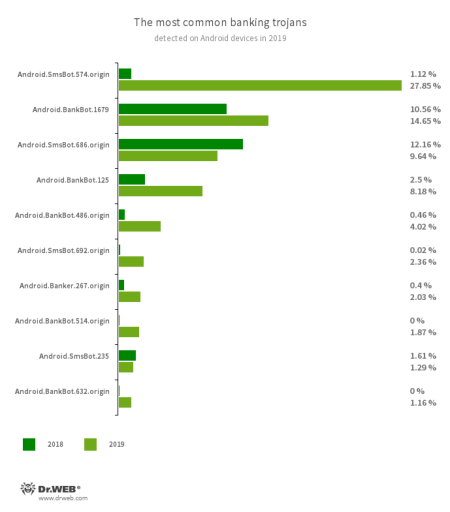

The most common threat for users were the Android.BankBot, Android.SmsBot, and Android.Banker trojan families. See the ten most widespread Android bankers of the year on the following diagram.

- Android.SmsBot.574.origin

- Android.SmsBot.686.origin

- Android.SmsBot.692.origin

- Android.SmsBot.235

- Trojans that execute cybercriminal commands. They can hook and send text messages, display fraudulent windows and notifications, and perform other malicious actions. Many of them are used to steal money from bank cards.

- Android.BankBot.1679

- Android.BankBot.125

- Android.BankBot.486.origin

- Android.BankBot.514.origin

- Android.BankBot.632.origin

- Part of the family of multifunctional banking trojans and capable of a wide range of malicious actions. Their main task is to steal credentials and other valuable information needed to access user accounts.

- Android.Banker.267.origin

- A banker that displays phishing windows and steals sensitive data.

For several years now, users have been attacked by various modifications of the Flexnet banking trojan, which belongs to the Android.ZBot family in the Dr. Web classification. This dangerous malware also threatened Android device owners in 2019. Virus writers spread it using SMS spam, inviting potential victims to download and install popular games and software.

Once on the device, Flexnet steals money from both bank accounts and mobile phone accounts. To do this, the trojan checks the balance of the available accounts and sends several text messages with money transfer commands. Thus, the cybercriminals can not only withdraw funds from the victim cards and transfer them to their accounts, but also pay for various services (for example, hosting providers) and make in-game purchases in popular games. Read more about this banker in our news article.

Over the past 12 months, banking trojans attacked residents of many countries. For example, Japanese users were threatened by numerous modifications of the Android.Banker trojan family that cybercriminals distributed via fake websites of mailing companies and courier delivery services.

In August and October, Doctor Web experts revealed the bankers Android.Banker.346.origin and Android.Banker.347.origin on Google Play. This malware was intended for Android users from Brazil. These dangerous applications, which were modifications of trojans detected in 2018, exploited the Android Accessibility Service. Thus, they stole information from text messages, which could contain one-time codes and other confidential data. These trojans could also open phishing pages at the command of cybercriminals.

Fraud

Cybercriminals continue using malware in various fraudulent schemes. For example, they create trojans that open websites and invite potential victims to take tests or polls by answering a few simple questions and getting a cash reward for that. However, to receive it, victims have to make a test payment, supposedly to confirm their identity or pay a fee for the transfer. In fact, this money goes to the bad guys and victims receive nothing.

Trojans of the Android.FakeApp family used in this scheme were widely used back in 2018, and our virus analysts recorded their activity again, which grew by 96.27% over the past 12 months. Cybercriminals put most of these malicious applications on Google Play. Android device owners looking for a quick buck do not realize when they’ve install a trojan instead of safe software.

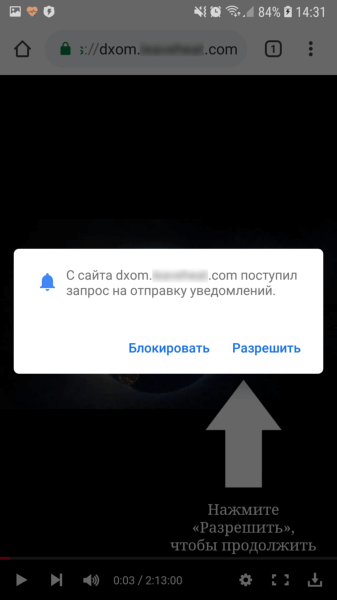

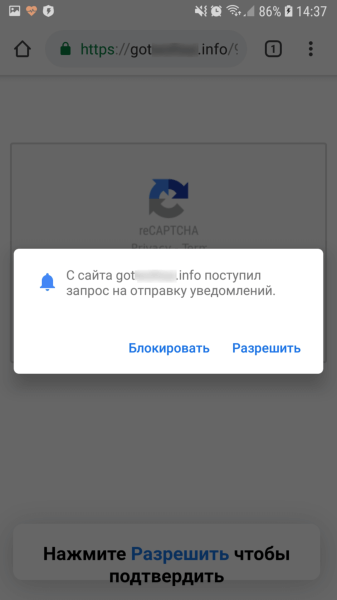

In early summer, Doctor Web specialists discovered another malicious application of this family, dubbed Android.FakeApp.174. It was distributed as official applications of popular stores.

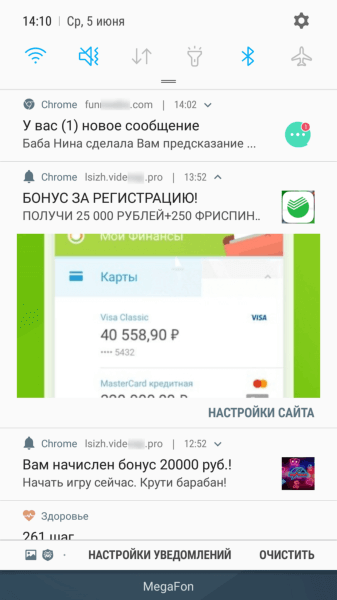

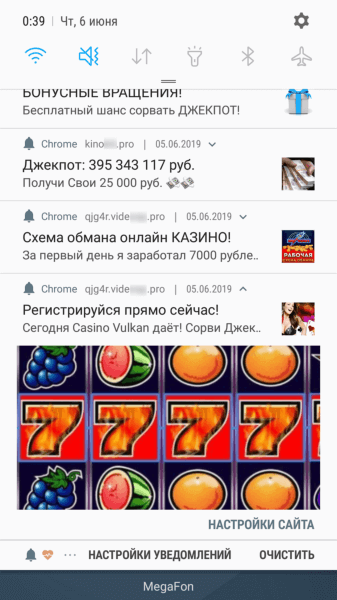

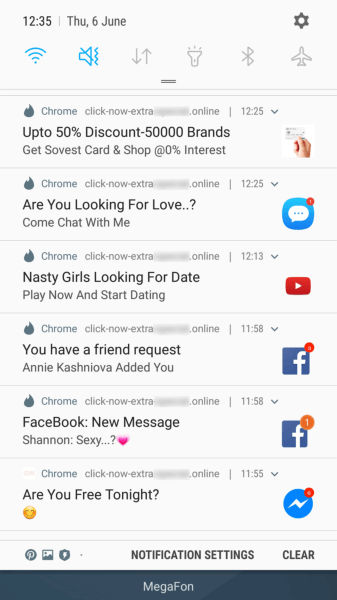

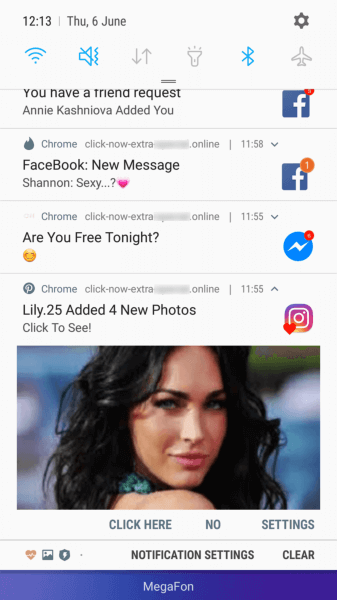

Android.FakeApp.174 opened websites that redirected users to pages of affiliate programs in Google Chrome. There, disguised as certain checks, users were asked to allow notifications from these websites.

If users agreed (and actually subscribed to web notifications), they began receiving various messages, often similar to notifications from well-known and reliable applications or online services, such as banking clients, social media, and instant messengers. By clicking on the messages, users were redirected to websites featuring dubious content, such as online casinos, fraudulent polls, fake prize draws, etc.

Prospects and trends

In the coming year, banking trojans will remain among the principle threats to Android device owners. They will continue to evolve and transform into universal malware that will perform a variety of malicious actions depending on the needs of cyber crooks. Mechanisms for protecting trojans and hiding the malicious code will be further developed.

Cybercriminals will continue targeted attacks, and users will still face the threat of cyber spying and leakage of confidential data. The issue of aggressive advertising will persist. More malicious and unwanted applications will display obnoxious banners and notifications, as well as trojans that download and try to independently install the advertised applications.

New miner trojans and malware built into the firmware of Android devices are likely to emerge. Until changes are made to the Android OS, trojans will continue exploiting the Accessibility Service and harm users.

Your Android needs protection.

Use Dr.Web

- The first Russian Anti-virus for Android

- More than 140 million downloads on Google Play alone

- Free for users of Dr.Web home products