Doctor Web’s annual virus activity review for 2017

December 29, 2017

In the context of information security, the past year will be remembered for such notable events as global attacks of encryption worms WannaCry, NePetya and BadRabbit, and also for a large number of Linux Trojans for so-called “Internet of things”. This year is also marked by the spreading of malicious scripts over numerous websites. These scripts were designed to mine cryptocurrency.

In spring 2017, Doctor Web security analysts researched a new backdoor for macOS. It was one of the few malicious programs for the Apple OS added to virus databases this year. During the past 12 months, new banking Trojans also emerged. They were designed to steal money from the accounts of clients of financial organizations: one of such malicious programs, Trojan.PWS.Sphinx.2, Doctor Web security specialists examined in February, and another—Trojan.Gozi.64—in November 2017.

Fraudsters showed high activity over the past year: Doctor Web regularly reported on revealing new schemes aimed at tricking Internet users. This past March, network fraudsters tried defrauding money from owners and administrators of various Internet resources. They created approximately 500 fraudulent webpages for this purpose. In their spam emails, cybercriminals tried to pass as “Yandex” employees and “RU-Center”. They also came up with a fraudulent scheme that required a victim to input their personal pension account number (SNILS). Additionally, in July, the Government Services Portal of the Russian Federation (gosuslugi.ru) was compromised. Unknown fraudsters injected potentially dangerous code into the Portal’s pages. This vulnerability was soon eliminated by the Portal’s administration.

2017 was also uneasy for owners of Android mobile devices. Over the summer, Doctor Web security analysts examined a multifunctional Android Trojan that gained control over a device and stole confidential information from customers of financial and credit organizations. A game with an embedded loader Trojan was quickly detected on Google Play. More than a million users had downloaded it. Over the course of the year, Doctor Web specialists detected Android Trojans pre-installed in factory firmware on mobile devices, as well as many other malicious programs and riskware for this platform.

Principal trends of the year

- The emergence of dangerous encryption worms capable of distributing themselves without user intervention

- A spike in the number of Linux Trojans for the “Internet of things”

- The spreading of dangerous malicious programs for Android

Most notable events of 2017

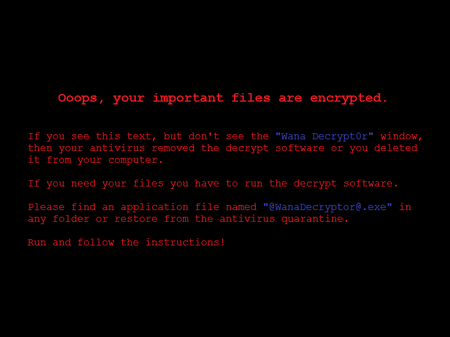

Encoder Trojans, which encrypt files and demand a ransom for their restoration, were usually spread as one or another “useful” tools or via malicious mailings. In addition, most often cybercriminals did not attach to emails an encryption Trojan itself but rather a small loader Trojan, which downloaded and launched an encoder upon an attempt to open an attachment. At the same time, worms capable of independently spreading across the network were not previously used to encrypt files. They had quite different malicious functions. Early in the year, Doctor Web specialists examined one of the representatives of a class of these malicious programs. The first encoder, which combined the capabilities of an encryption and network worm, was Trojan.Encoder.11432. It became widely known as WannaCry.

Mass spreading of this malicious program started around 10 a.m. on May 12, 2017. In order to infect other computers, the worm used a vulnerability in the SMB protocol (MS17-10), and under its threat were both local network hosts and computers on the Internet with random IP addresses. The worm consisted of several components, and the encoder was just one of them.

Trojan.Encoder.11432 encrypted files using a random key. In addition, the Trojan contained a special decoding module that allowed users to decode several files for free in a demo mode. It is notable that randomly selected files were encrypted using an entirely different key, so their restoration did not guarantee the rest of the data would be successfully decoded. A detailed examination of this encoder was published on our website in May 2017.

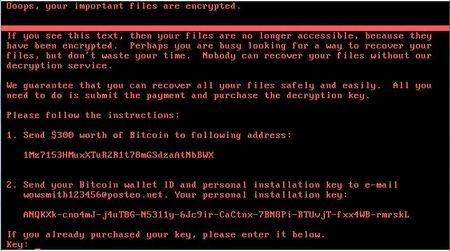

Shortly thereafter another outbreak occurred of the encryption worm, dubbed NePetya, Petya.A, ExPetya and WannaCry-2 by various sources (it received these names due to its similarity to the Petya Trojan—Trojan.Ransom.369,— which was spread earlier). NePetya was added to the Dr.Web virus databases under the name Trojan.Encoder.12544.

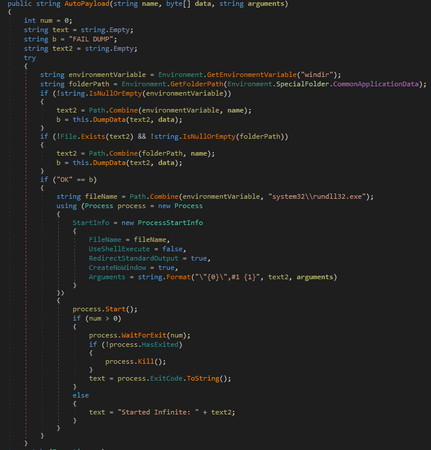

As its predecessor WannaCry, the encryption worm Trojan.Encoder.12544 was used for distributing the vulnerability in the SMB protocol. However, in this case it did not take long to determine the distribution source of the worm. It was an updated module of the program M.E.Doc designed for inputting of tax reports in Ukraine. That is why Ukrainian users and organization were the first victims of Trojan.Encoder.12544. Doctor Web specialists examined in detail the program M.E.Doc and decided one of its components contained a full-featured backdoor, which was capable of collecting authorization credentials to access mail servers, loading and launching any applications on a computer, and executing arbitrary commands in a system, and also sending files from a computer to a remote server. NePetya used this backdoor, just as at least one encryption Trojan did before.

Research of Trojan.Encoder.12544 showed that this encoder was not intended for decrypting corrupted files. Additionally, it had a rather wide variety of malicious functions. To intercept account data of Windows users, it used Mimikatz tools. It utilized this information (and also several other methods) to spread across a local network. To infect accessed computers, Trojan.Encoder.12544 used a program for remote control called PsExec or a standard console tool Wmic.exe for calling objects. In any case, the encoder damaged a boot record of the disk С: (Volume Boot Record, VBR) and replaced an original Windows boot record (MBR) with its own, while encrypting the original MBR and moving to another sector of the disk.

In June, Doctor Web published a detailed research report on the encryption worm Trojan.Encoder.12544.

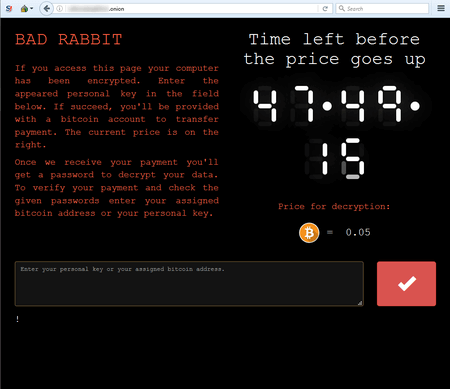

In October, one more encoder worm was detected. It was dubbed Trojan.BadRabbit. Known samples of the Trojan were spread as a program with an installer icon for Adobe Flash. Architecturally, BadRabbit was similar to its two predecessors. It also consisted of several components: a dropper, an encoder, and a network worm. It also contained a built-in decryptor. Moreover, a portion of its code was clearly adopted from Trojan.Encoder.12544. However, this encoder had one distinguishing trait: once launched, it checked an attacked computer for two anti-viruses—Dr.Web and McAfee—and, in case of their detection, it skipped the first encryption stage. Apparently, it attempted to avoid early detection.

For more information about this malicious program, refer to the news article published by Doctor Web.

Virus situation

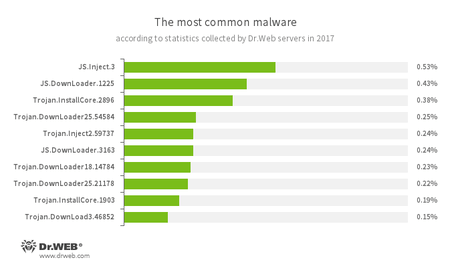

According to data obtained using the Doctor Web statistics servers, in 2017 users’ computers were most often infected with scripts and malicious programs designed to download other Trojans from the Internet and also to install dangerous and unwanted applications. Compared to the previous year, adware has almost disappeared from these statistics.

- JS.Inject

- A family of malicious JavaScripts. They inject a malicious script into the HTML code of web pages.

- JS.DownLoader

- A family of malicious JavaScripts. They download and install malicious software on a computer.

- Trojan.InstallCore

- A family of installers of unwanted and malicious applications.

- Trojan.DownLoader

- A family of malicious programs designed to download other malware to the compromised computer.

- Trojan.Inject

- A family of malicious programs that inject malicious code into the processes of other programs.

- Trojan.DownLoad

- A family of malicious programs designed to download other malware to the compromised computer.

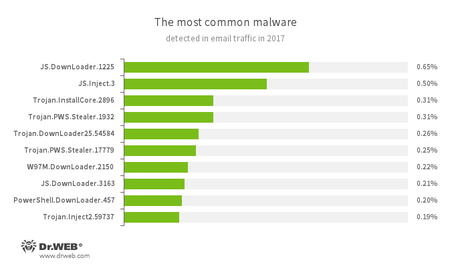

There is a similar situation with analysis of email traffic. However, besides loaders, there are also Trojans designed to steal passwords and other confidential information.

- JS.DownLoader

- A family of malicious JavaScripts. They download and install malicious software on a computer.

- JS.Inject

- A family of malicious JavaScripts. They inject malicious script into the HTML code of webpages.

- Trojan.InstallCore

- A family of installers of unwanted and malicious applications.

- Trojan.PWS.Stealer

- A family of Trojans designed to steal passwords and other confidential information stored on an infected computer.

- Trojan.DownLoader

- A family of malicious programs designed to download other malware to the compromised computer.

- W97M.DownLoader

- A family of downloader Trojans that exploit vulnerabilities in office applications. Designed for downloading other malware to a compromised computer.

- PowerShell.DownLoader

- A family of malicious files written in PowerShell scripts. They download and install malicious software on a computer.

- Trojan.Inject

- A family of malicious programs that inject malicious code into the processes of other programs.

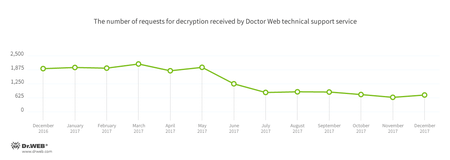

Encryption ransomware

It is safe to say that 2017 was the year of encoding worms. It was exactly in 2017 when encryption ransomware learned how to massively spread across a network without any actions from users. This resulted in several outbreaks. In the past 12 months, Doctor Web technical support received around 18,500 requests from users who suffered from acts of encryption ransomware. Starting in May, the amount of requests began gradually reducing. In comparison with the start of the year, by the end of 2017 the amount had been reduced by half.

According to statistics, the Trojan that most often penetrated computers was Trojan.Encoder.858, the second place went to Trojan.Encoder.3953, and the third most “popular” encoder was Trojan.Encoder.567.

The most common ransomware programs in 2017:

- Trojan.Encoder.858 — 26.55% requests;

- Trojan.Encoder.3953 — 6.03% requests;

- Trojan.Encoder.567 — 3.71% requests;

- Trojan.Encoder.761 — 1.79% requests;

- Trojan.Encoder.3976 — 1.07% requests.

- Receive a list of the contents of a specified directory;

- Read a file;

- Write to a file;

- Get the contents of a file;

- Delete a file or folder;

- Rename a file or folder;

- Change the privileges for a file or folder (chmod command);

- Change the owner of a file object (chown command);

- Create a folder;

- Execute a command in the bash shell;

- Update the Trojan;

- Reinstall the Trojan;

- Change the command and control server’s IP address;

- Install a plug-in.

Dr.Web Security Space for Windows protects against encryption ransomware

Linux malware

As in 2016, during the last 12 months, a lot of Linux Trojans were detected. Cybercriminals created versions of dangerous applications for such architectures as х86, ARM, MIPS, MIPSEL, PowerPC, Superh, Motorola 68000, and SPARC, i.e. for a very wide range of “smart” devices. Among them are all kinds of routers, set-top boxes, network drives, etc. Many users of such equipment do not think they need to change the default account data of a system administrator, and it significantly simplifies the task of cybercriminals.

At the end of January 2017, Doctor Web virus analysts detected several thousand devices infected with Linux.Proxy.10. This malicious program is designed to launch the SOCKS5 proxy server on an infected device. Cybercriminals use this server to stay anonymous on the Internet. One month later, Trojan.Mirai.1 was detected. This Windows Trojan is capable of infecting Linux devices.

In May, Doctor Web specialists examined a new modification of a complicated multi-component Linux Trojan that belongs to the Linux.LuaBot family. This malicious program is a set of 31 Lua scripts and two additional modules, each of which performs its own functions. The Trojan infects devices possessing the following architectures: Intel x86 (and Intel x86_64), MIPS, MIPSEL, Power PC, ARM, SPARC, SH4, and M68k—in other words, not only computers, but also a wide array of routers, set-top boxes, network storages, IP cameras and other “smart” devices.

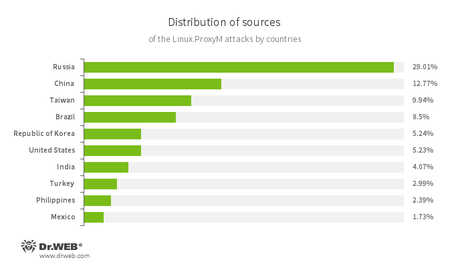

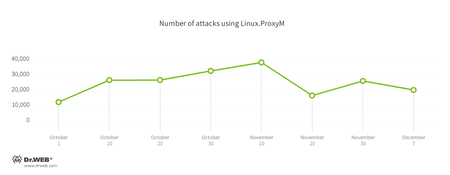

In July, a signature of Linux.MulDrop.14 was added to the Dr.Web virus databases. This Trojan installed a cryptocurrency-mining application on the devices it infected. At the same time security researchers examined Linux.ProxyM, a malicious program that launched a proxy server on an infected device. Attacks involving this Trojan have been noted since February 2017 but peaked in late May. Most of the attack sources were located in Russia, China and Taiwan were on the second and third places respectively.

Soon cybercriminals started using Linux.ProxyM to send spam and phishing emails, in particular from the DocuSign service designed to work with electronic documents. Doctor Web specialists were able to learn that cybercriminals had sent around 400 spam messages per day from each infected device. In autumn 2017, cybercriminals found one more use for Linux.ProxyM: they used it to hack websites. They used several methods of hacking: SQL injections (an injection of a malicious SQL code into a request to a website database), XSS (Cross-Site Scripting)—an attack method that involves adding a malicious script to a webpage, which is then executed on a computer when this page is opened, and Local File Inclusion (LFI)—an attack method that allows cybercriminals to remotely read files on an attacked server. The chart with the number of registered Trojan attacks is presented below.

Also in November, a new Linux backdoor was detected. It was named Linux.BackDoor.Hook.1. It can download files indicated in a command it receives from cybercriminals, launch applications, or connect to a specific remote host.

Number of threats for Linux gradually increases, and there is every reason to believe this trend will continue next year as well.

Malicious programs for macOS

During the year, Dr.Web virus databases were updated with signatures of a whole range of malicious program families capable of injecting Apple devices. They are Mac.Pwnet, Mac.BackDoor.Dok, Mac.BackDoor.Rifer, Mac.BackDoor.Kirino and Mac.BackDoor. and MacSpy. One of the malicious programs detected is 2017 is Mac.BackDoor.Systemd.1. It is a backdoor that executed the following commands:

For more information regarding this Trojan, refer to the news article published by Doctor Web.

Dangerous and non-recommended sites

Doctor Web specialists regularly add website addresses to the Parental (Office) control databases. These addresses are considered potentially dangerous or not recommended for users. They are fraudulent and phishing resources and websites that distribute malicious software. The dynamics of the database update in 2017 is shown in the following diagram.

Network fraud

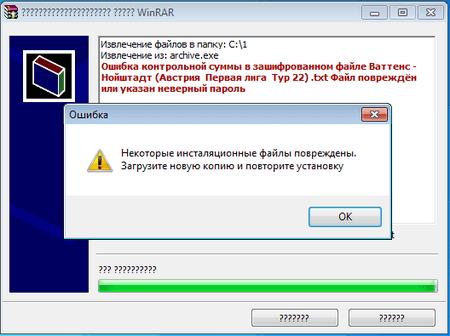

Internet scams are a rather widespread event. Every year network fraudsters develop their range of methods for defrauding trusting users. One of the popular fraudulent schemes of 2017 used the so-called “fixed matches”. Cybercriminals created a special website that offered for sale “reliable and verified information on the results of sporting events”. Buyers later use this information to make supposedly sure-win bets at bookmakers’ offices. This spring cybercriminals improved their scheme: they offered their potential victims the opportunity to download a password-protected, self-unpacking RAR archive that supposedly contained a text file with the match results of an event. Cybercriminals sent the password for this archive after the match was finished. This was supposed to give users a chance to compare the predicted outcome with the real one. However, instead of this archive, they downloaded a program created by cybercriminals. Visually it did not differ from a self-unpacking WinRAR archive. This fake “archive” contained the template of a text file that, with the help of a special algorithm, inserted the required match results that depended on what password is entered by the user. Thus, when the match was finished, the only thing that cybercriminals had to do was to send their victim the appropriate password, and the text file with the correct result would be “extracted” from the “archive” (in reality, the Trojan would generate it on the basis of the template).

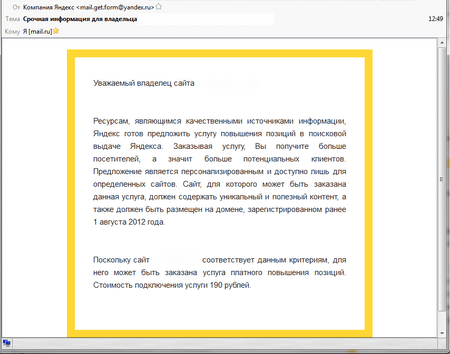

In the last year, cybercriminals tried tricking not only ordinary users but also website owners. Fraudsters sent them emails allegedly on behalf of Yandex. Supposedly they took email addresses from domain registrars’ databases. In their messages, on behalf of Yandex, the criminals offered a website owner to boost their position in search results. For these purposes, they created more than 500 webpages. Doctor Web specialists added links to these webpages to the list of non-recommended websites.

Cybercriminals sent fraudulent emails not only on behalf of Yandex, but also on behalf of the domain registrar RU-Center. Cybercriminals referred to some changes in the ICANN rules and offered that the domain administrators create the PHP file with certain contents in the root directory. The creation of this file was supposed to confirm the email recipient’s right to use the domain. The file suggested for saving in the root directory contained a command that executed an arbitrary code specified in a variable.

Another popular method of tricking users is a promise to pay large sums of money for an insignificant withdrawal fee. Doctor Web reported on such scheme that required an indication of a personal insurance policy number (SNILS) or a passport number in order check insurance payouts owed to a user.

We can suppose that cybercriminals will further invent new methods to illegally make money by tricking users.

Mobile devices

Mobile devices are still an attractive target for cybercriminals. Therefore it is not a surprise that 2017 was again marked by an emergence of a large number of malicious and unwanted programs. Among cybercriminals’ main targets were an unlawful enrichment and stealing of personal information.

As before, one of the main threats were banking Trojans used by cybercriminals to obtain access to client accounts of financial organizations and covertly steal their money. Among such malicious applications, it is worth noting Android.Banker.202.origin, which was embedded into benign programs and distributed via Google Play. Android.Banker.202.origin is interesting for its multi-stage attack scheme. Once launched, it extracted a hidden inside Trojan called Android.Banker.1426, which downloaded one more malicious banker. This banker specifically stole logins, passwords and other confidential information required to access client accounts.

A similar banker was dubbed Android.BankBot.233.origin. It extracted from its resources and covertly installed Android.BankBot.234.origin, which hunted for information on banking cards. This malicious program tracked the launch of Google Play and displayed on top of it a fraudulent form with a request for corresponding data. The feature of Android.BankBot.233.origin was its attempt to obtain access to Accessibility Service of infected devices. With its assistance, it started to fully control smartphones and tablets and their functions. Due to this access to a special operation mode, Android.BankBot.233.origin covertly installed another Trojan.

Android.BankBot.211.origin is one more dangerous banker, which also used Accessibility Service of Android. The Trojan independently assigned itself a device administrator and SMS manager by default. In addition, it was able to record everything that happened on a screen and made screenshots with every tap on a keyboard. Android.BankBot.211.origin also displayed phishing windows to steal logins and passwords and sent cybercriminals other confidential data.

The application of Android Accessibility Service by malicious programs made them more dangerous and became one of the main evolution stages for Android Trojans in 2017.

Still important were Trojans that covertly downloaded and launched various applications. One of them was Android.Skyfin.1.origin, which was detected in January. The Trojan injected itself into the process of Play Store and downloaded software from Google Play. Android.Skyfin.1.origin increased the number of installs in the catalog and artificially increased popularity of applications. In July, Doctor Web security researchers detected and examined Android.Triada.231. Cybercriminals injected it into one of the system libraries of multiple Android device models. This Trojan injected itself into processes of all running programs and could covertly download and launch malicious modules indicated in a command of a command and control server. Cybercriminals started applying such mechanism for process infection back in 2016, and Doctor Web specialists anticipated that virus writers continue using this attack vector.

In 2017, owners of Android smartphones and tablets faced adware again. Among them was Android.MobiDash.44, which spread via Google Play as manual applications to popular games. This Trojan displayed advertisements and could download additional malicious components. In addition, new unwanted advertising modules were detected, one of them was named Adware.Cootek.1.origin. It was embedded into a popular keyboard application and distributed also via Google Play. Adware.Cootek.1.origin displayed advertisements and various banners.

In 2017, ransomware Trojans again posed a serious threat to mobile device users. These malicious applications block a display of an infected smartphone or tablet and demand a ransom to unlock them. Sums that interest cybercriminals can reach up to several hundreds and even thousands of dollars. During the past 12 months, Dr.Web anti-virus products for Android detected such type of Trojans on user devices over 177,000 times.

Android.Locker.387.origin was among the detected in the past year Android ransomware. It was hidden in an application for performance optimization and battery “restoration”. Another Android locker dubbed Android.Encoder.3.origin did not only block the screens of attacked devices but also encrypted files. Android.Banker.184.origin, besides encrypting, changed the password for display unlocking.

In 2017, there were a lot of threats on Google Play. In April, Android.BankBot.180.origin was detected there. It stole login credentials to access banking accounts and intercepted SMS messages with verification codes. Later, Android.Dvmap.1.origin was detected. It attempted obtaining a root access for covert installation of a malicious component Android.Dvmap.2.origin. It downloaded other Trojan’s modules.

In early July, Doctor Web virus analysts detected a malicious program on Google Play dubbed Android.DownLoader.558.origin. It covertly downloaded and launched additional components. In the same month, Android.RemoteCode.85.origin was detected in the catalog. The Trojan downloaded a malicious plugin that stole SMS messages.

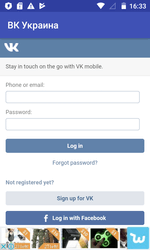

In autumn, security specialists found Android.SockBot.5 on Google Play. It turned infected smartphones and tablets into proxy servers. Later, a loader was detected in the catalog. This Trojan downloaded and offered users to install various programs. It was named Android.DownLoader.658.origin. Among the malicious applications detected on Google Play was also a riskware Program.PWS.1. Doctor Web wrote about it in one of its articles. This application allowed the program to connect to the “VK” and “Odnoklassniki” websites, which are blocked in Ukraine. However, it did not encrypt sent data, including login credentials.

In the past year, cybercriminals also attacked owners of Android devices with spyware. Among these malicious programs were Android.Chrysaor.1.origin, Android.Chrysaor.2.origin, and also Android.Lipizzan.2, which stole correspondence from popular programs for online communication, SMS messages, tracked coordinates of infected devices and sent cybercriminals other confidential data. One more spyware was dubbed Android.Spy.377.origin. It received commands via the Telegram protocol and had a wide functionality. For example, the Trojan could send SMS with a pre-defined text to numbers indicated by cybercriminals, collected information about all available files and sent any of them to the command and control server at the request of cybercriminals. In addition, Android.Spy.377.origin could make phone calls and track location of smartphones and tablets.

Among the detected malicious programs for mobile devices were also new miner Trojans. For example, Android.CoinMine.3, which mined the Monero cryptocurrency.

Prospects and possible trends

As before, the most dangerous Trojans are encoders and bankers. We can expect an emergence of new encryption ransomware that uses errors and vulnerabilities of an operating system and network protocols.

There is a serious possibility of growth in the amount of threats for “smart” devices running Linux. The number of models of such devices has gradually increased; and, combined with their low cost, the “Internet of things” will inevitably be attractive not only for ordinary users but also for cybercriminals.

Apparently, in 2018, the number of Android malicious programs will not reduce. At least, currently no tendency for reducing the activity of “mobile” cybercriminals exists. Despite all protection measures, Trojans for Android smartphones and tablets will emerge on Google Play and also in the firmware of some devices. The most dangerous Trojans will be bankers capable of stealing money directly from account in financial organizations as well as blockers and encoders.

Among loader Trojans, distributed in malicious mailings, it is most likely small scripts will dominate. they will probably be written using VBScript, Java Script, Power Shell. Even now, many scripts in emails detected by the Dr.Web anti-virus products exist. There will be new methods for mining cryptocurrency without the obvious consent of users. Without doubt, the number of information security threats will not reduce in 2018.