Overview of handheld malware for 2014

Virus reviews | Hot news | Threats to mobile devices | All the news | Virus alerts

February 24, 2015

The situation on the handheld malware front

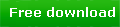

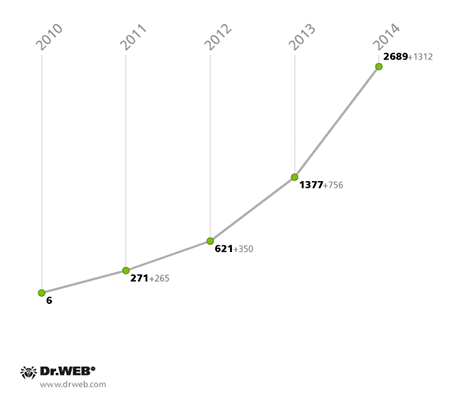

The past year was rather eventful in terms of emerging new malicious applications being used by criminals to attack smartphones and tablets running Android, particularly iOS. At the same time, Android continued to maintain its leading position on the handheld market, so it's hardly surprising that cybercriminals have made this OS their primary target. By the end of 2014, the Dr.Web virus database expanded by 2,867 new entries for various malicious, unwanted, and potentially dangerous applications and held a total of 5,681 definitions—showing 102% growth compared with the same period in 2013. And compared with 2010, when the first definitions for Android malware appeared in the Dr.Web virus database, the figure has increased 189 times, or 18,837%.

Growth in the number of entries for malicious, unwanted, and potentially dangerous programs for Android during the period 2010-2014

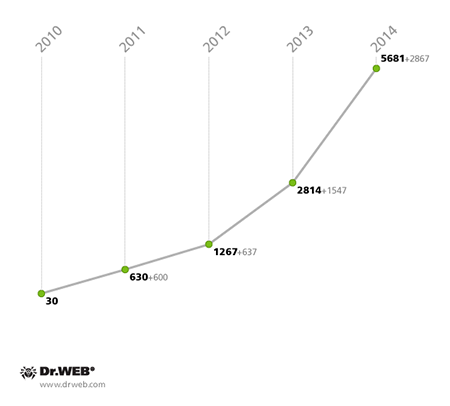

As the amount of malware and unwanted software for Android grew through 2014, so did the number of new Android malware families—it reached 367, which is 11% more than the 331 families known at the end of 2013.

The number of families of Android malware, and unwanted, potentially harmful software

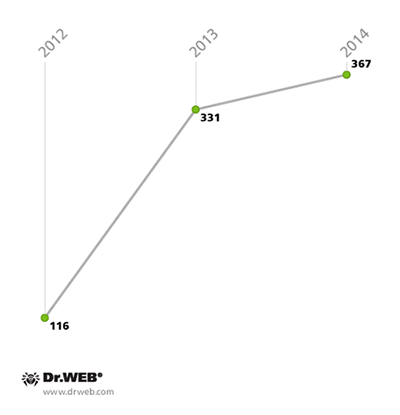

As before, Trojans that steal confidential information or provide criminals with other ways of generating illicit income were some of the most abundant malware applications for Android in 2014. Ideas for new Trojan designs were often inspired by malicious programs for desktops and laptops.

The most common malware for Android as determined by Dr.Web virus definitions

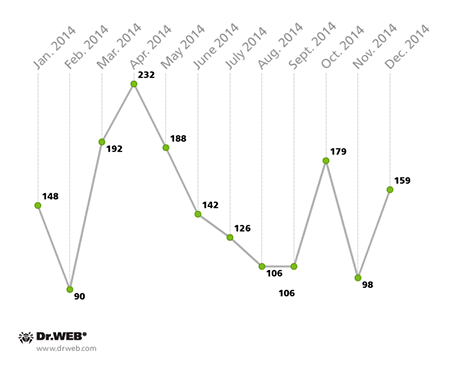

Attackers keep profiting from premium SMS messages

Fraud schemes aimed at subscribing victims to chargeable services or covertly sending short messages to premium numbers remain the most common way for those attacking handheld devices to make money illegally. So it’s no wonder that Android.SmsSend programs, whose sole purpose this is, remained the unequivocal leaders among Android malware programs—the number of definitions for these programs doubled in the past year, reaching 2,689 entries. Thus Android.SmsSend programs account for almost half of all the malware and software known to be harmful to Google Inc.’s mobile OS.

Android.SmsSend malware definitions in the Dr.Web virus database

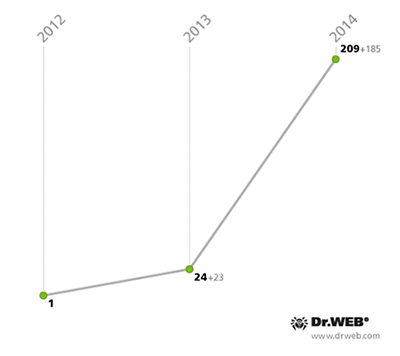

Malicious programs from other families facilitate the transmission of SMS messages to premium numbers too. Android.SmsBot programs are the next step in the evolution of SMS Trojans. Like their relatives, they can covertly send short messages to subscribe users to chargeable services. However, unlike their predecessors, these programs are directly controlled by criminals and follow their commands. This greatly enhances the malware’s functionality. Apart from sending messages, Android.SmsBot programs steal confidential information, make phone calls, and download other malware. First discovered in 2013, these programs became more intensively used over time. By the end of 2014, the Dr.Web virus database included 209 definitions for Android.SmsBot malware programs, while at the end of 2013, there were only 24—the nine-fold or 771% increase clearly indicates that criminals are becoming increasingly interested in this malware.

Android.SmsBot virus definitions in the Dr.Web virus database

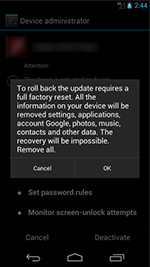

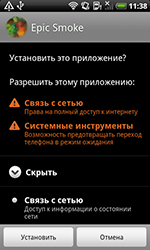

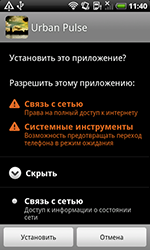

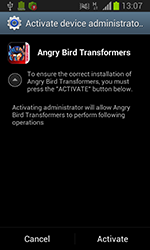

Yet, enterprising criminals didn't stop there; they expanded their premium SMS profit arsenal even further with Trojans of the new Android.Bodkel family which also covertly send expensive messages. However, they also steal sensitive information and relay it to a remote server.Android.Bodkel Trojans are distinguished by their attempts to acquire administrative permissions on a device (this option is available in most modern Android versions) in order to complicate their removal. If, after removing them from the administrator list, a user still tries to uninstall one of these Trojans, Android.Bodkel programs try to prevent this by displaying a message that threatens to destroy all of the device owner’s available data, although in reality neither this nor a system reset actually occurs.

|

|

Virus makers also obfuscate this malware’s code to make it more complicated for anti-virus companies to analyse it, and to make it less likely that security software will detect it—this is another distinguishing feature of these programs. In 2014, the Dr.Web virus database received 113 entries for Android.Bodkel programs, making it possible for Doctor Web specialists to detect a large variety of modifications of this Trojan.

Mobile banking Trojans hunt for subscribers' money

Remote banking services, particularly mobile banking, are becoming more and more popular among users. Cybercriminals could not simply ignore this fact, so it's no wonder that their attacks on handhelds have intensified through the years. They employ a substantial variety of malicious programs to gain access to user bank accounts in many countries. On infected devices, these malicious programs can steal account access passwords, intercept SMS messages containing mTANs, transfer money to criminal accounts, steal other confidential information and covertly send short messages to specified numbers.

With its developed market of online banking services, South Korea has become one of the most attractive regions for money-hungry criminals. To spread malicious Android applications on devices in South Korea and to get to the customers of its financial institutions, enterprising virus writers made heavy use of unsolicited SMS messages containing Android Trojan download links. According to statistics gathered by Doctor Web, over the past 12 months, cybercriminals organised over 1,760 such spam campaigns involving about 80 different malicious programs for Android, as well as many modifications of them.

Number of spam campaigns orchestrated in 2014 to distribute Android Trojans in South Korea

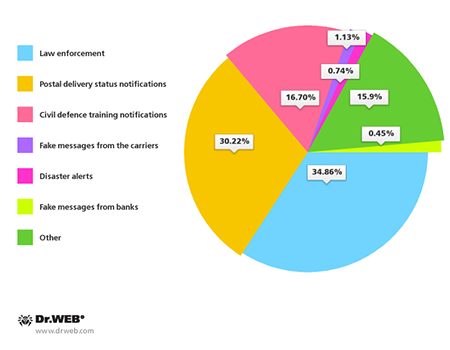

To get their targets interested in spam messages enough to open a download link, criminals supplement the link with a socially meaningful message. The most popular topics include postal delivery tracking, invitations to all sorts of events including weddings and meetings, as well as criminal offence reports and notifications about civil defence exercises. In addition, messages were sent on behalf of banks, telecom providers and popular online services. Criminals weren’t the slightest bit squeamish about using news about large scale technological and natural disasters and accidents as an irresistible lure.

Topics of spam messages used by criminals to spread Android malware in South Korea

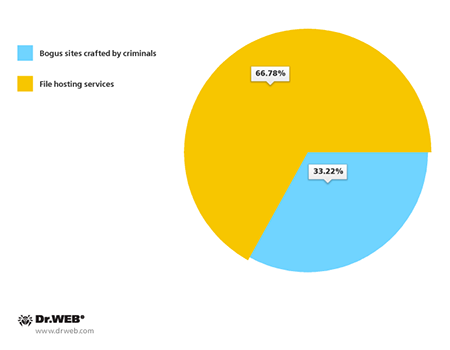

Users who opened links in messages of this kind were typically redirected to a bogus site involved in hosting and spreading malware or ended up on a page of a file-sharing service employed by criminals for the same purpose. It is noteworthy that in most cases (66.78%), criminals preferred file-sharing services or other means freely available to the general public to spread their malicious applications. Unlike websites of their own making, those require neither effort nor money to design and maintain.

Sites that hosted the Android malware being spread in South Korea

The magnitude of South Korean spam campaigns enabled criminals to impact from several hundred to tens of thousands of people. For example, in April, Doctor Web registered the mass distribution of the Trojan program Android.SmsBot.75.origin which stole confidential information and could execute commands from criminals to send short messages to specific numbers. Cybercriminals distributed this malicious program in South Korea via fraudulent webpages disguised as sites belonging to postal delivery services. It is noteworthy that one of those sites was visited by over 30,000 people, and the total number of potential victims could exceed this figure considerably. During a similar attack in May, the number of victims could have been even greater because at that point, one of the fraudulent webpages had been visited more than 70,000 times.

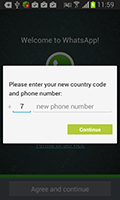

Screenshots showing examples of sites crafted by virus makers to spread malware in South Korea in 2014

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Criminals using file-sharing services to host and spread Android malware in South Korea

|

|

|

|

Many Trojans employed by attackers in South Korea incorporated a rather extensive payload and sophisticated design. For example, in order to steal valuable information, many banking Trojans (including Android.Banker.28.origin) used a somewhat unusual approach. When launched, they would check whether official online banking applications were installed on the device and if they were, the malware would imitate their interface and prompt the user to divulge sensitive information, such as their login and password, credit card number, personal information and even a transaction security certificate. Sometimes these Trojans (e.g., Android.BankBot.35.origin) acted in a more straightforward way and simply offered to update the user’s mobile banking software. In reality, a malicious copy of the application would be installed to steal whatever information the criminals needed.

|

|

|

South Korean virus makers applied various packers and code obfuscation techniques to make it less easy for anti-viruses to detect the malware. Furthermore, cybercriminals very often hid malicious Android applications by employing all kinds of droppers belonging to the Android.MulDrop family, to deliver malware to targeted devices. Android.SmsSpy.71.origin is a typical example of a program that utilises a combination of similar protective techniques. Its various modifications were not only protected by complex packers, but were also distributed by specially crafted dropper Trojans. Android.SmsSpy.71.origin was designed to intercept SMS messages, steal users’ contact information, and block calls. This Trojan can also respond to criminals’ commands to carry out mass SMS mailings to select phone book numbers or to all of them.

It is also worth mentioning that in some cases, South Korean Trojans didn't just conceal themselves from users and popular anti-viruses but also attacked the latter rather aggressively and attempted to remove the anti-viruses whenever they discovered the Trojans in the system.

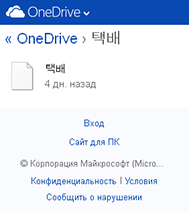

The twenty most common Android Trojans in South Korea in 2014 are presented on the figure below.

The most common malware spread via SMS mailings in South Korea in 2014

Russia also saw quite a few capable Android banking Trojans in 2014. Discovered in autumn by Doctor Web security researchers, Android.BankBot.33.origin, Android.BankBot.34.origin and Android.BankBot.1, deserve special attention. Android.BankBot.33.origin stole money from bank accounts accessed via online banking. The malware attempted to obtain information about current bank account balances or the list of bank cards associated with individual mobile phones. To do so, it sent SMS message requests to the automatic service systems of several Russian financial organisations. If Android.BankBot.33.origin received a reply, it used SMS commands to transfer the available funds to the attackers' account. In addition, the Trojan was able to load phishing webpages in device browsers to steal the credentials required to access user online banking accounts.

Android.BankBot.34.origin bore a similar payload. In addition to possessing the ability to covertly transfer money from bank accounts, the malware could also acquire logins and passwords stored by a number of popular applications, and gather information about the phone number and credit card associated with a compromised device. Moreover, Android.BankBot.34.origin could display any message or dialogue box on an infected device and, thus, the device could be used by cybercriminals in the most diverse fraud schemes. Furthermore, because the Trojan's command and control (C&C) server resided in the Tor network, the makers of Android.BankBot.34.origin could maintain a high level of secrecy and make it more difficult for anyone to bring down their remote host. However, in case the principal C&C server did become unavailable, the malware could connect to back-up servers located in the regular Internet.

|

|

|

Android.BankBot.1, another malicious program with a similar payload, was spread in Russia via SMS mail messages containing its download link. Like other malicious applications of this family, Android.BankBot.1 could steal money from bank accounts; however, unlike many Android Trojans, most of its malicious features were implemented in Linux libraries located outside the main malware executable. This could make the malware invisible to many anti-virus applications and prolong Android.BankBot.1’s existence on infected mobile devices.

Bank customers in other countries didn't escape the attention of criminals either. For example, in November Brazilian users were threatened by two banking Trojan spies lodged in the Google Play catalogue: Android.Banker.127 and Android.Banker.128. When launched on an Android smartphone or tablet, these malicious applications would display a fraudulent webpage requesting a potential victim to submit their bank account access credentials. The information acquired was then transmitted to the attackers.

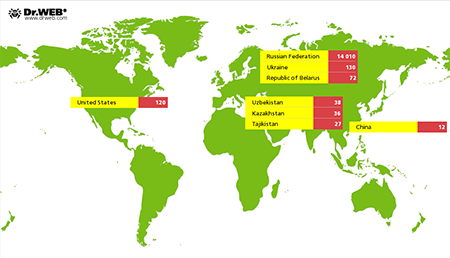

Special attention needs to be paid to Android.Wormle.1.origin which in November 2014 infected over 15,000 Android handhelds in about 30 countries including Russia, Ukraine, the USA, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and China. The program could not only execute attacker commands to covertly transfer money from a victim's credit card, but also perform a variety of other harmful tasks, for example, send an SMS, delete installed programs and files, steal a variety of confidential information, and even carry out DDoS attacks on websites. In addition, Android.Wormle.1.origin could spread with the help of SMS messages containing its download link.

Number of devices infected by Android.Wormle.1.origin in November 2014

Ransomware lockers and mining Trojans generate revenue

The emergence of several new types of malicious applications created by cybercriminals for illegal gain was one of the key trends of the past year. In particular, in May the first-ever Trojans capable of locking mobile devices and demanding a ransom from users were discovered. These applications provided criminals with easy money, so the subsequent rapid upsurge in the quantity of these applications was hardly surprising. So, if in May the Dr.Web virus database contained only two entries for Android ransomware, by the end of 2014, that figure increased by 6,750% and reached 137 units.

Discovered in May, the dangerous locker program Android.Locker.2.origin, which was also the first full-fledged encryption ransomware for Android, came to be considered one of the most remarkable programs of this kind. When launched on an infected device, this program would search the memory card for file names containing the extensions .jpeg, .jpg, .png, .bmp, .gif, .pdf, .doc, .docx, .txt, .avi, .mkv, and .3gp, encrypt the files, and lock the screen before displaying a ransom demand for their decryption.

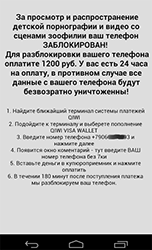

It should be noted however, that for now criminals still prefer less vicious versions of the malware, and most known Android ransomware programs merely lock devices and accuse their owners of committing all kinds of crimes such as viewing and storing adult content illegally. This intimidation technique was used in attacks on devices in various countries, and false accusations were typically made on behalf of the police, investigators, and other law enforcement agencies of the country in which the malware operated. For example, discovered in June, Android.Locker.6.origin and Android.Locker.7.origin were being distributed in the United States by virus writers. When launched, these programs would lock devices because illegal content had allegedly been discovered on them, and then on behalf of the FBI, they would demand that the victim pay a $200 fine to unlock their handhelds. In addition, these Trojans would steal data from phone address books (including contact names, phone numbers and email addresses), and track incoming and outgoing calls, and, if necessary, block them. In addition, the Trojans would check whether certain applications belonging to various financial institutions were found on an infected device and then they would transmit the information collected to the attackers.

|

|

|

|

owever, virus writers didn't stop at blocking mobile devices and displaying threats. For example, discovered in September, the extortionist Android.Locker.38.origin, like most other malicious applications of its kind, would block handheld screens by displaying a ransom demand. But beyond that, it would set a standby unlock password which would greatly complicate attempts to neutralise this Trojan.

However, the new programs discovered in 2014 weren’t limited to ransomware. In 2013, various Trojans designed to exploit the resources of infected machines in order to mine cryptocurrencies were widespread on desktop PCs. Apparently, their success encouraged makers of malware for handhelds, and the first programs of this kind for Android appeared in early 2014. Of special note were the Android miners (included in the Dr.Web virus database as Android.CoinMine.1.origin and Android.CoinMine.2.origin) designed to mine Litecoin, Dogecoin, and Casinocoin. Discovered in March, these Trojans were distributed by attackers in modified popular applications and would spring into action when mobile devices were not being used by their owners. Since the malware made heavy use of the hardware resources of the smartphones and tablets they infected, the devices could experience overheating and shorter battery life. Users could even lose money as a result of the malware’s excessive consumption of Internet traffic.

|

|

|

April 2014 saw new versions of the Trojans designed to mine bitcoins being discovered on Google Play. These malicious applications were hidden in innocuous "live wallpaper" and would also begin their illegal activities after infected mobile devices lay dormant for a certain amount of time.

|

|

Unlike similar programs discovered in March, the new members of the Android.CoinMine family received a number of upgrades from their makers—in particular, the maximum amount of hardware resources used was limited. However, these malicious applications could still do some damage; for example, they could cause increased expenses due to significant data exchange on the Internet.

Confidential data still a target

Virus makers aren’t just out to get hold of users' money. They just as eagerly hunt for their confidential information which can yield just as much of a profit. In 2014, information security experts registered scores of such attacks, many involving highly sophisticated malicious applications.

For example, an entry for Android.Spy.67.origin, which spread in China in the guise of software updates, was added to the Dr.Web virus database in January. This malicious program was installed in the guise of popular applications and created several corresponding shortcuts on the home screens of the devices it compromised. When launched, Android.Spy.67.origin deleted the shortcuts and collected personal information which included SMS history, call log, and GPS coordinates. In addition, the malware could activate the camera and microphone of the mobile device; it could index images and creates thumbnails of them. All the information acquired was uploaded to an intruder-controlled server. Android.Spy.67.origin had another peculiar feature: if the malware gained root access, it would disrupt the operation of popular Chinese anti-viruses, remove their virus databases, and install a malicious program that could, in turn, covertly install other applications.

In spring 2014, security researchers also found numerous remarkable spying Trojans attacking Android-powered devices. In early March, cybercriminals began commercially distributing another "mobile" spy. Dubbed Android.Dendroid.1.origin, the malware could be embedded into any harmless Android app and enabled attackers to carry out a number of illegal actions on infected mobile devices: intercept calls and SMS messages, get information about current device location, gain access to the phone book and browsing history, activate the device camera and microphone, and send short messages. Android.Dendroid.1.origin was sold on underground hacker forums, which attests to the fact that the market for illegal services for the Android OS has been growing.

Also in March, Doctor Web discovered a rather unusual backdoor that was subsequently dubbed Android.Backdoor.53.origin. In order to spread this program, the criminals behind it modified Webkey, a legitimate application that lets users control their mobile devices remotely. Unlike the original version, the compromised application didn't have a GUI and after installation, it hid its presence in the system by removing its icon from the main screen. When launched, Android.Backdoor.53.origin sent the device's ID to a remote server, signalling that the infection was initiated successfully. Consequently, the intruders could get full control over the device and gain access to the personal data and hardware features.

In August 2014 information security specialists discovered another dangerous backdoor for Android. Under the Dr.Web classification system, it was given the name Android.Backdoor.96.origin. The criminals behind this Trojan disguised it as an anti-virus program; it could perform numerous illegal actions on an infected mobile device. This program stole all sorts of confidential information including SMS data, call and browsing history, GPS data and contact information. In addition, Android.Backdoor.96.origin could display various messages on the device's screen, send USSD queries, toggle on the device's microphone, record phone calls and upload the gathered information to a remote server.

However, Android.SpyHK.1.origin, which appeared in the wild at the end of September, was one of the best-equipped spying Trojans for Android. This malicious program was designed to infect the mobile devices of people protesting on the streets of Hong Kong. When launched, it would upload a large amount of general information about the smartphones or tablets it infected successfully to a server controlled by criminals. Then the malware would stand by for instructions. It could execute commands to eavesdrop on phone calls, steal SMS messages, determine a device's location, upload the files stored on the memory card to the server, activate voice recording, and acquire browsing history and contact information. In fact, Android.SpyHK.1.origin could be used by cybercriminals as a full-fledged spyware program to obtain the most detailed information about the users of the infected mobile devices.

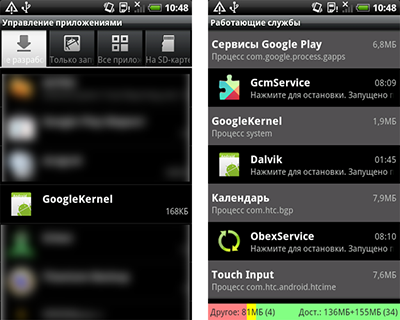

Trojans pre-installed on mobile devices and the first-ever bootkit for Android

One way cybercriminals have found to spread malicious software programs for the Android OS is to either embed them in files (e.g., Android firmware) that are then posted on the Internet where they can be downloaded by users, or pre-install them on mobile devices. This method has several advantages for attackers. First, hidden this way, malware can remain "in the shadows" and operate successfully for a long time, without attracting attention. Second, even if the embedded Trojan is exposed, most users are unlikely to be able to do anything about it since removing the unwelcome intruder entails either obtaining root privileges or installing clean firmware which results in total data loss. In the worst case scenario, the victim will either have to just put up with the malicious software running on their phone or simply exchange it for another Android smartphone or tablet.

The last year witnessed several incidents involving malicious applications being hidden in Android OS firmware distributed online, as well as pre-installed malware being found on some mobile devices. One of the most notable cases involving similar Trojans occurred in January, when the malicious application Android.Oldboot.1 was discovered. It represented the first bootkit for Android. This Trojan resided in the protected memory area, so it could run in the early Android loading stage and was very hard to remove completely. When launched, Android.Oldboot.1 extracted several components and put them in the system folders, installing them as ordinary applications. These malicious objects then connected to a remote server and could execute whatever unwanted actions they were instructed to carry out. In most cases, they covertly downloaded, installed and removed various programs.

A little later, security researchers discovered an upgraded version of this Trojan. In this case, some of the installed malware components incorporated obfuscated code. They removed themselves after being launched and continued to operate only in the memory. This very same Trojan, Android.Oldboot, gained the ability to uninstall a number of popular anti-virus programs present on infected devices.

In February, Doctor Web discovered several applications, designed to covertly send short messages, embedded in Android firmware. One of them in particular, Android.SmsSend.1081.origin, worked as an audio player that sent out SMS messages containing IMSI identifiers to try to automatically subscribe users to a Chinese online music site. It is noteworthy that the Trojan did not control the number of SMS messages being sent. Every time it was launched, it dispatched messages, emptying the subscriber's account by an insignificant amount of money. Android.SmsSend.1067.origin featured a similar payload and was embedded into a system application. It also covertly sent messages of this kind but relayed the handheld’s IEMi instead of the SIM card ID.

|

|

Also hidden on a number of Android-powered devices was the Trojan program Android.Becu.1.origin which was discovered by Doctor Web security researchers in November. Criminals embedded this malicious application into the firmware used on a large number of inexpensive smartphones and tablets that run the Android OS. This program featured a modular architecture. Once launched, the malware downloaded additional components from its C&C server which were then used to execute the intruders’ commands to covertly download, install and remove certain applications. If any of the Trojan's components were removed, Android.Becu.1.origin would download and install itself again to restore its operational capabilities. Furthermore, this malicious application could block all SMS messages received from certain phone numbers.

Discovered in December, Android.Backdoor.126.origin was another malicious program that was deployed by criminals on a range of mobile devices. This malicious program could execute commands to generate short messages containing specific texts and add them into the message inbox which enabled enterprising criminals to use it in the most diverse fraud schemes. A definition for a similar malicious program was added into the Dr.Web virus database in November. However, that one—Android.Backdoor.130.origin—came with a more extensive array of features. Specifically, it could covertly send short messages; make calls; display ads; and download, install, and launch applications; as well as transmit all sorts of confidential information, including call and SMS history and location data, to a remote server. In addition, Android.Backdoor.130.origin could remove applications that had already been installed on infected devices, and execute a slew of other undesirable actions.

Attacks on Apple handhelds

Even though many cybercriminals view mobile devices running Android as their main target, they relentlessly pursue additional sources of extra income and turn to other popular mobile platforms. For example, in 2014 intruders orchestrated a series of attacks on devices manufactured by the Apple Corporation. Owners of unaltered iOS smartphones and tablets came under fire as did owners of jailbroken handhelds.

In March, IPhoneOS.Spad.1, which targeted jailbroken devices and modified the parameters of some advertising modules embedded in various applications for iOS, was discovered in China. The profit generated by the advertisement was subsequently channelled to an account belonging to enterprising hackers rather than to the authors of those programs. In April, another Trojan was found that also attacked jailbroken mobile devices in China. Classified by Dr.Web as IPhoneOS.PWS.Stealer.1, the malware stole Apple ID credentials on devices compromised by the Trojan. Compromised Apple IDs can affect the ability of users to access most Apple services, including App Store and iCloud. In May, Chinese jailbroken devices were assaulted by the Trojan IPhoneOS.PWS.Stealer.2. Similar to IPhoneOS.PWS.Stealer.1, the Trojan stole Apple ID logins and passwords, but could also download and install other applications, including those that it bought automatically in App Store at the expense of unsuspecting users.

Yet another malicious program designed to infect jailbroken iOS devices was discovered by security researchers in September. This program entered the Dr.Web virus database as IPhoneOS.Xsser.1 and proved to be rather dangerous. IPhoneOS.Xsser.1 could be commanded to steal such confidential information as the contents of the phone book, photos, passwords, SMS and call history and device location. In December, jailbroken devices were assailed by the spying Trojan IPhoneOS.Cloudatlas.1. This malware was designed to steal a wide range of sensitive data, including detailed information about the infected devices (starting with the version of the operating system and ending with the current time zone), as well as information on available user accounts, including AppleID and iTunes credentials.

All these incidents show exactly how dangerous it is to use iOS devices whose integrity-monitoring software has been compromised. But sometimes even complying with security basics doesn't guarantee full protection for ‘mobile assistants’ manufactured by the Cupertino-based corporation. An attack occurring in November 2014 that targeted jailbroken handhelds as well as devices with an intact iOS serves as clear evidence of this. The attack involved Mac.BackDoor.WireLurker.1—a malicious application that infected machines running Mac OS X. It was used to install IPhoneOS.BackDoor.WireLurker onto smartphones and tablets manufactured by Apple Inc.

Virus makers embedded Mac.BackDoor.WireLurker.1 into counterfeit copies of various legitimate applications (often expensive ones), making it very likely that the Trojan would be installed by careless users who were unwilling to pay for apps and games. Once the Trojan infected its next Mac, it would wait for a mobile device that would suit its purposes to connect to the Mac via USB, and as soon as the next smartphone or tablet was connected, the Trojan would use a special security certificate to immediately install IPhoneOS.BackDoor.WireLurker onto it. This backdoor could steal confidential information, including contact information and SMS messages, which was then relayed to an intruder-controlled server.

Unusual threats in 2014

Sometimes in their pursuit of profit, resourceful virus writers produce malicious applications whose payloads differ from the payloads of the majority of other Trojans. One such rarity was Android.Subscriber.2.origin which subscribed users to chargeable services. The main difference between this Trojan and similar ones that cybercriminals have produced is that Android.Subscriber.2.origin subscribes users to paid services by registering their phone number on a bogus website rather than by sending a short message. The Trojan registers a phone number on the portal and awaits an SMS message containing the operation confirmation code. The malware hides the SMS reply, reads its contents and automatically sends the acquired code to the same website, to complete the registration. However, this is not the only surprise Android.Subscriber.2.origin has for users. Once the supposedly requested premium messages begin to arrive on the device, the Trojan hides them in the inbox by marking them as ‘read’ and changing their date of receipt to 15 days prior.

However, sometimes virus makers are driven by motives other than some kind of material gain. Discovered by security researchers in September, Android.Elite.1.origin is a vivid example of this. Once located on a mobile device, this Trojan would format the available memory card and disrupt the normal operation of numerous online chat and SMS applications by blocking access to their windows with the message OBEY or Be HACKED.

|

|

In addition, this malicious program would send mass short messages to all of the contacts found in the phone book, activity that could deplete the user's mobile account.

Prospects and likely trends

Numerous diverse attacks on handhelds in the past year indicate that in 2015 smartphone and tablet owners will have to take mobile device security even more seriously.

Keeping their bank accounts safe from cybercriminals will most likely become one of the most pressing issues for users. The rapid development of online banking makes it a tempting morsel for criminals, so attacks involving various banking Trojans will intensify. The threat from programs that send premium SMS messages will persist. Users should also be wary of attacks by new ransomware, programs that virus makers get particularly enthusiastic about. More sophisticated attacks with this sort of malware are likely to occur, and it is quite likely that new mobile mining Trojans will emerge.

In addition to keeping their finances safe, users would do well to take extra care to maintain the integrity of their personal information. This is a valuable asset which rivals money in terms of how popular it is with intruders.

The likelihood that new malware will emerge for Apple-manufactured devices is also rather high. Therefore, fans of Mac OS X and iOS should pay special attention to security basics: Refrain from visiting bogus sites, avoid opening links from unknown sources, and whenever possible abandon jail-breaking for the purpose of installing dubious software.