Doctor Web’s review of threats to Android in 2013

Virus reviews | Hot news | Threats to mobile devices | All the news | Virus alerts

January 27, 2014

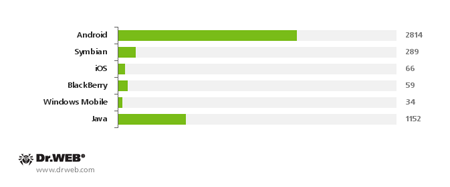

Threats to Android in 2013: Overall statistics

Last year's developments in IT security once again confirmed that Android has definitively strengthened its status as the main mobile platform through which criminals are conducting illegal activities. This assertion is supported by the growing number of entries in the Dr.Web virus database for 2013: as many as 1,547 entries, corresponding to malicious and unwanted applications for Android, were added to the database, and the total number of virus definitions reached 2,814. This is 122% more entries than the number of entries made to the database at the end of the same period in 2012. Compared with the figure for 2010, when the first malicious applications for Android appeared, the number has increased by 9,280%, i.e., it grew nearly 94 times.

Android virus definitions’ growth in numbers from 2010 till 2013.1.png)

In contrast, in late 2013 the total number of virus definitions related to other popular mobile platforms, such as BlackBerry, Symbian OS, Java, iOS and Windows Mobile, was 1,600—1.76 times fewer entries than those for Android threats.

Virus definitions for mobile threats in 2013

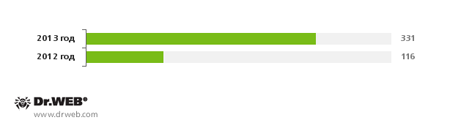

New families of malware and potentially dangerous software for Android also grew in number and reached 185% of the value for 2012, their total number reaching 331.

Total number of families threatening Android

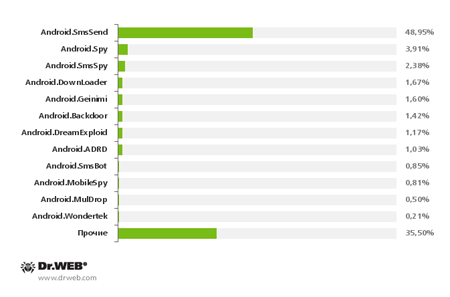

Based on an analysis of the current contents of the Dr.Web virus database, the most abundant Android threats are as follows:

The most numerous threats to Android as found in the Dr.Web virus database

SMS Trojans—a major threat

The statistics above show that Android.SmsSend Trojans were the undisputed leaders among malware programs in 2013. Such programs first appeared in 2010. They are designed to covertly send expensive SMS messages and subscribe users to paid content services for which payment is debited from user accounts. The number of Android.SmsSend modifications more than doubled, reaching 1,377. The overall growth in the number of SMS Trojans can be traced in this chart displaying the number of corresponding entries in the Dr.Web virus database for the period from 2010 till 2013:

Fluctuations in the growth of Android.SmsSend virus definitions.1.png)

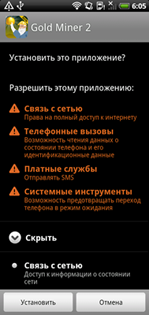

These Trojans can be spread in the guise of updates and installers for popular applications or can be embedded into legitimate programs that have been modified by criminals. It should be noted that the latter approach has been rather popular in —in large number of modifications of similar SMS Trojans appeared, threatening Chinese users. However, over the last 12 months, similar malicious applications targeting Android-powered devices were found in . This indicates that this method of spreading Android.SmsSend programs has not only remained relevant, but also has become even more popular among cybercriminals. It should be noted that among applications, games are the primary targets for modification.

If a user launches this type of modified software package, they get all the functionality they are expecting, while malicious activities such as sending short messages go unnoticed. It is very likely that this approach will remain popular and that criminals in other countries will employ it, too.

| |

|

|

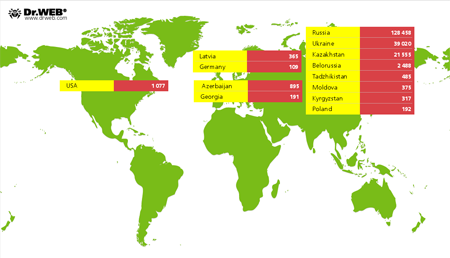

The discovery of one of the largest botnets comprised of Android-powered devices infected with these malignant programs was a notable event. According to Doctor Web's analysts, the botnet included more than 200,000 smartphones and tablets, and the potential damage to users could exceed several hundred thousand dollars. To infect mobile devices, attackers used several SMS Trojans that were disguised as installers of legitimate software, e.g., web browsers and social networking client programs. The image below illustrates the countries in which the compromised mobile devices were found.

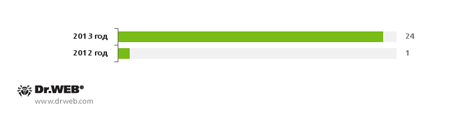

Android.SmsBot is the logical evolution of SMS Trojans

In 2013, virus analysts faced an increasing number of incidents involving relatively new malicious programs such as Android.SmsBot malware. These malicious applications represent the next step in the design of widespread Android.SmsSend programs: their main purpose remains the unauthorized transmission of premium messages to generate illicit profit for criminals. However, unlike most of their predecessors, which had their operational parameters hardcoded or specified in configuration files, these Trojans acquire their configuration information from criminals which significantly increases their flexibility. In particular, short message texts and target phone numbers can be changed when necessary. Many Android.SmsBot Trojans can perform other actions, such as downloading other malware, removing specific SMS, collecting and sending information about the mobile device to a remote server, and making calls. In addition, some modifications to these malicious applications can request mobile account balance information using SMS or USS, and, depending on the result, they can be directed by a command and control server to send a message to a chargeable number.

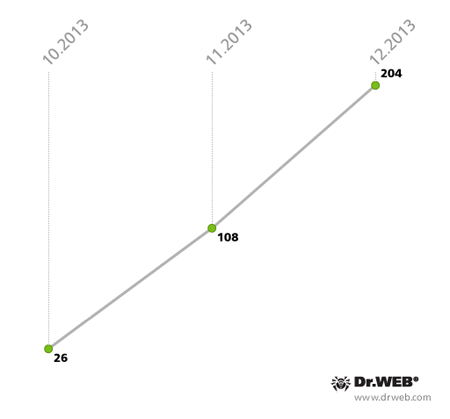

It is indicative that at the end of 2012, the Dr.Web virus database contained only one Android.SmsBot entry, while in 2013 their number had already reached 24. This trend reveals the growing interest of intruders in greater flexibility and better organisation for their criminal activities, so it is very likely that more modifications of programs like this will appear soon enough.

Android.SmsBot virus definitions

Growing threat to confidential information: Banking Trojans, personal information theft and spyware

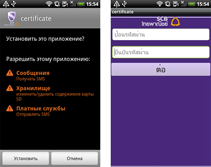

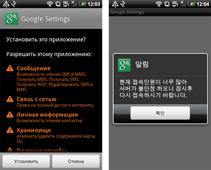

For many users of Android handhelds, protecting their personal information became an urgent issue in 2012, and 2013 was no different: over the past twelve months, security specialists have observed a significant increase in the number of malicious programs specialising in stealing personal information from Android smart phones and tablets. The newly emerged malware includes banking Trojans, namely Android.Tempur and Android.Banker programs, as well as Android.SmsSpy, Android.SmsForward, Android.Pincer and Android.Spy. Most of these applications mimic the interface of legitimate mobile banking programs and lure users into providing their personal data. Others hide under the guise of important software updates or certificates and, when installed, enable attackers to intercept all incoming SMS messages, which may contain sensitive information such as mTAN codes and passwords.

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

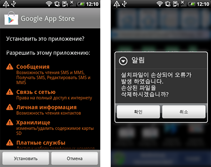

||||

If in 2012 the number of malicious applications like these did not exceed several species and their distribution was limited to only a small list of countries, in 2013 the situation changed dramatically: incidents involving attacks by banking Trojans occurred in Russia, Thailand, the UK, Turkey, Germany, Czech Republic, Portugal, Australia, South Korea and other countries. We'd like to pay special attention to the threat presented by banking malware in South Korea, since banking Trojans were spreading in this region on a large scale in 2013. Doctor Web's analysts registered 338 incidents involving the distribution of different versions of these malicious applications over the last quarter of 2013. To spread the malware, criminals sent SMS messages containing a download link to a malicious APK file, and a text urging the user to check the status of their supposed shipment or access other important information. Fluctuations in the discovery of such incidents are illustrated in the diagram below.

Identified incidents involving banking Trojans for Android on devices located in South Korea

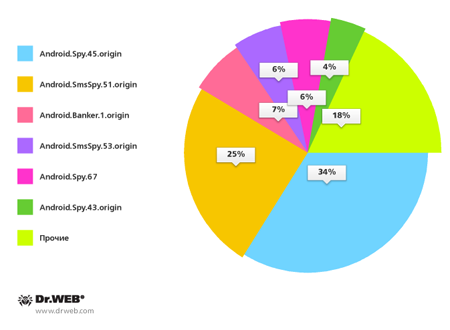

South Korean users most often ran the risk of downloading Trojan-spy programs such as Android.Spy.45.origin, Android.SmsSpy.51.origin, Android.Banker.1.origin, Android.SmsSpy.53.origin, Android.Spy.67 and Android.Spy.43.origin. The percentage of malware for Android involved in infection incidents is shown in the following illustration.

Threats to Android in South Korea in the last three months of 2013

The volume of other Trojans that steal information also increased significantly: in 2013 many such malicious applications were added to the Dr.Web virus database. They include Android.Phil.1.origin, Android.MailSteal.2.origin, Android.ContactSteal.1.origin, and several modifications in the families Android.EmailSpy and Android.Infostealer. These malignant programs provided criminals with phone book information. Android.Callspy.1.origin enabled attackers to obtain information about calls. Also discovered were an array of similar multi-purpose malicious programs that facilitated activities such as tracking a device's location, and obtaining information about the device, the applications installed on it, and the files stored on the SD card. These are, for example, Android.Roids.1.origin, Android.AccSteal.1.origin, and malicious applications of the family Android.Wondertek.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Potentially dangerous commercial spyware that can covertly monitor user activity on a device came into the spotlight, too. In the past year, new versions of such popular spyware as Android.MobileSpy, Android.SpyBubble and Android.Recon were discovered, as well as new similar programs, namely, Program.Childtrack.1.origin, Program.Copyten.1.origin, Program.Spector.1.origin, Program.OwnSpy.1.origin and Android.Phoggi.1.origin, and many others.

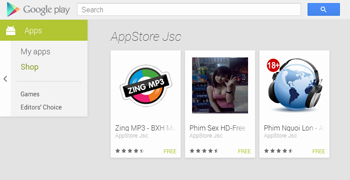

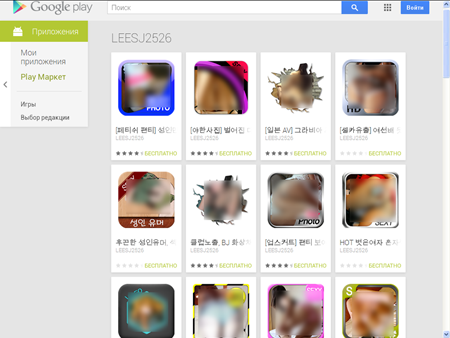

Threats on Google Play

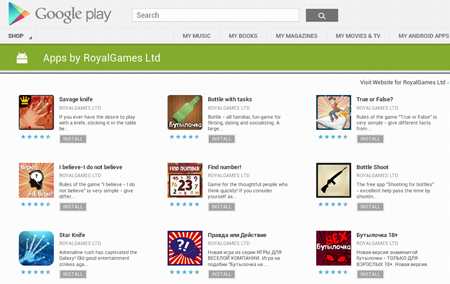

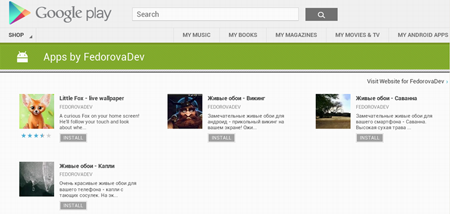

Despite the fact that Google Play is considered to be one of the safest sources of software for Android, there is still no guarantee that it is completely free of malicious or potentially dangerous applications. The discovery of several threats on the portal in 2013 is clear proof of this.

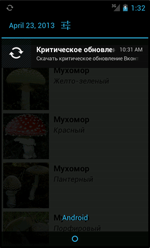

For example, several programs discovered in April incorporated the malignant advertising module Android.Androways.1.origin which demonstrated ads that would lure users into downloading Trojan horses. Criminals created the module under the guise of a harmless ad network that displays a variety of messages. Developers can integrate the module into their software so that it generates revenue. Similarly to legal ad network modules, Android.Androways.1.origin displayed push notifications in the status bar; however, these messages could be used to show fake prompts to update various programs. If the user agreed to perform an ‘update’, they risked downloading an Android.SmsSend onto their device.

In addition, Android.Androways.1.origin was capable of executing a number of commands from a remote server and uploading to the server such information as the device's phone number and IMEI, and the operator code. The total number of devices compromised by the malware could exceed 5.3 million—one of the largest incidents in the history of malicious applications spreading via Google Play.

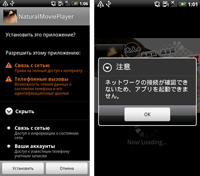

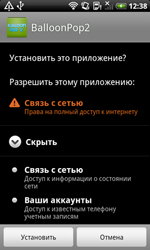

In the summer of 2013, Doctor Web's analysts identified several applications from a Vietnamese developer, who positioned them as media players, while, in fact, they were Trojans containing Android.SmsSend. When virus analysts discovered the programs (dubbed by Dr.Web as Android.MulDrop, Android.MulDrop.1 and Android.MulDrop.2), they had already been downloaded more than 11,000 times.

When launched, the malicious application would offer to grant the user access to the requested content, and then would extract and install the concealed Trojans. Later, the installed SMS Trojans, classified by Doctor Web as Android.SmsSend.513.origin and Android.SmsSend.517, would start sending short messages to premium numbers, which entailed unplanned financial expenses.

In December, 48 image-collection programs were discovered and their total number of downloads exceeded 12,000. When launched, these applications worked as expected. However, in addition to offering the declared features, they would also secretly transmit the compromised device's phone number to a remote server. Interestingly, these Trojans, which entered the Dr.Web virus database as Android.Spy.51.origin, are only interested in the phone numbers of South Korean subscribers. Considering this fact as well as the names of the applications and their descriptions in Korean, we assume South Koreans were the main target group for these malignant programs. The acquired phone numbers could be used later in promotions or sold to third parties, including advertising companies and even cybercriminals capable of orchestrating phishing attacks.

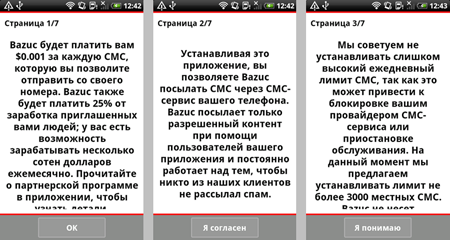

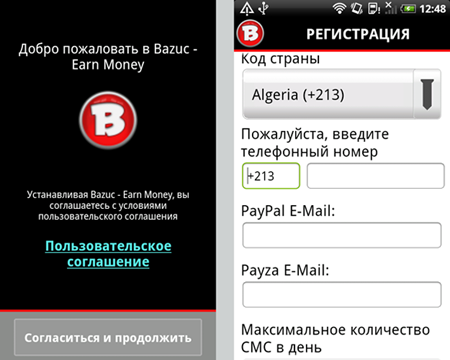

In addition, two more threats were found on Google Play in December, namely, Android.WhatsappSpy.1.origin and the potentially dangerous program Program.Bazuc.1.origin.

The first threat was merely a game that would covertly upload the database of WhatsApp for Android onto a server belonging to the Trojan's authors. The program would also transmit to the server images and the phone number associated with user accounts. Later, anyone could get access to the user correspondence. They just had to enter the mobile number of the person in whom they were interested on the Android.WhatsappSpy.1.origin maker's site. Despite the fact that the application was positioned as a harmless backup tool for WhatsApp messages, the risk posed by the unauthorised use of collected data forced Google to remove this program from Google Play. Nevertheless, it is available for download from the official website of its developer, so many users are still at risk of becoming victims of espionage.

|

|

The second application, called Bazuc, allowed users to make money by allowing the program to send promotional and informational SMS messages from their mobile phone. The author of Program.Bazuc.1.origin intended for the program to be used by Android device owners whose plans included unlimited SMS messaging, but if that feature was not included, careless users risked getting enormous bills for thousands of sent SMS messages, having their accounts suspended or getting sued by the message recipients who would be able to see the sender’s phone number.

These incidents show once again that despite Google's security efforts, Google Play can still be a source of a wide variety of threats. Therefore, users should exercise caution when dealing with applications that are obscure or suspicious.

Operating system vulnerabilities

Android upgrades increase operating system reliability and security, but at times vulnerabilities are discovered. These can be exploited by cybercriminals to carry out a variety of attacks which may involve the use of malware. While 2012 witnessed no discoveries whatsoever of critical vulnerabilities or any serious incidents involving the use of Trojan applications, over the past 12 months several software flaws were found that could allow attackers to circumvent the protection mechanisms of Android and spread Trojans more efficiently. In particular, the most notable vulnerabilities—Master Key (# 8219321), Extra Field (# 9695860) and Name Length Field (# 9950697)—allowed software packages to be modified without affecting the integrity of their digital signature; so, during installation, they were considered unmodified by Android.

It is noteworthy that the flaws were related to routines for handling specific features of ZIP files which typically store Android applications. In the case of Master Key, two files with the same name from the same directory could be placed into an APK file (a ZIP archive with the extension .apk). As a result, during the installation of the modified application, Android ignored the original file and used the duplicate added into the archive by intruders. The Android.Nimefas.1.origin Trojan, discovered by Doctor Web in July, can serve as a typical example of the vulnerability's exploitation. This malicious program is a multi-purpose Trojan targeting Chinese users and capable of executing commands (e.g., it can send a bulk of short messages, intercept incoming messages, gather information about a mobile device and the contacts in its address book, etc.).

The second vulnerability—Extra Field—theoretically also allowed criminals to add malicious features into applications by modifying the extra field size value in the header of the executable stored in the ZIP archive (in particular, the file classes.dex) and by adding malicious code at the supposed location of the original code , so that the file is perceived as legitimate. Despite the fact that criminals exploiting the vulnerability are limited by the size of a DEX file, which must not exceed 65,533 bytes, they can easily take advantage of it once they modify a harmless application that incorporates an appropriately sized component.

As far as the Name Length Field vulnerability is concerned, its exploitation also requires package modification when two files with the same name (the original file and the dodgy one) are present in the package. When such a package is being installed, the original file is verified by Android, but after that the installer processes only the modified file.

All APK files that exploit similar software flaws are detected as Exploit.APKDuplicateName by Dr.Web for Android.

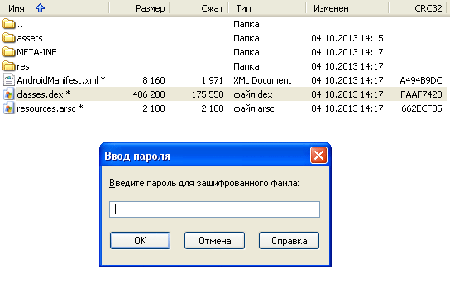

Another potentially dangerous feature of Android discovered in 2013 was the ability to install packages that have an attribute of a password-protected ZIP archive. The attribute would not prevent a package from being installed under certain versions of the OS but would hamper its scanning by anti-viruses which considered such packages protected and, therefore, would not attempt to gain access to their contents. In particular, this technique was employed by the authors of Android.Spy.40.origin which was discovered by Doctor Web's analysts in October. This malware was designed primarily to intercept incoming SMS messages, but could also perform some other tasks. Now that the corresponding routines in Dr.Web for Android have been readjusted, such threats are being detected successfully.

|

|

Concealed malicious activity, and resistance to analysis, detection and removal

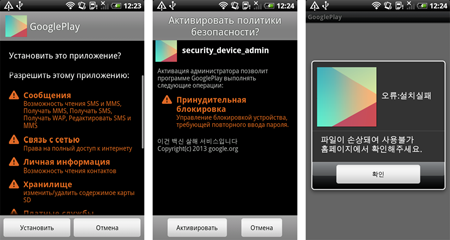

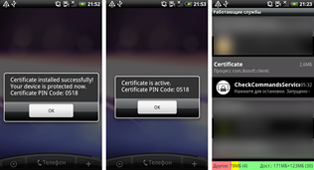

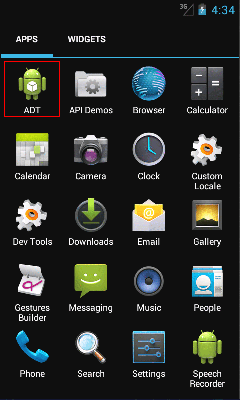

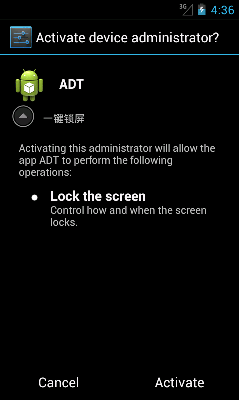

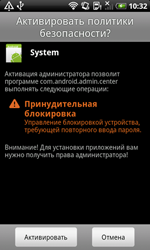

In 2013, virus writers used special techniques that hinder the analysis of malicious applications and complicate their detection and removal much more frequently. One very common self-defense technique employed by Android Trojans involved acquiring administrative privileges. This enabled them to lock the screen, request a password when the device resumes operation from standby mode, and even reset settings to default, removing all available data in the process. Criminals liked this feature because any normal attempt to remove the application from the administrator list resulted in an error.

This situation is not a problem for experienced users—they only need to deprive the Trojan of the corresponding privileges—but many less tech-savvy handheld owners are facing difficulties in cleaning their mobile devices of infection. Some spy and several SMS Trojans use this kind of protection.

However, sometimes revoking privileges is not enough—virus writers enable Trojans to monitor whether the user is attempting to turn them off and to respond with resistance. For example, they can prevent the user from opening the system settings or display a prompt that keeps hounding users into granting the Trojans privileges.

Android.Obad programs, discovered in the early summer of 2013, make use of this protection mechanism. These programs also send SMS messages to premium numbers and download other malicious applications to the mobile device. These Trojans used administrator privileges and exploited an operating system flaw that allowed them to hide their presence on the administrator list. This significantly complicated their removal.

|

|

|

The growing number of software products on the market that protect Android software from reverse-engineering, hacking, and program modification have become another security problem, since these tools can be employed not only by legitimate software developers, but also by Trojan makers. In the past year Doctor Web's analysts discovered several instances of such software being incorporated into Trojans, e.g., Android.Spy.67 and Android.Tempur.5.origin. In addition, virus writers are still actively using code obfuscation to hamper analysis of the Trojans.

Dr.Web anti-viruses for Android receive timely upgrades to neutralise threats that apply various protection mechanisms, so these malicious programs are not dangerous for devices protected with Dr.Web.

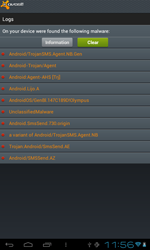

Fake anti-viruses

The number of Android.Fakealert programs—fake anti-viruses that display false infection warnings and offer neutralisation services for a fee—increased significantly during the last 12 months. The number of corresponding entries in the Dr.Web virus database quintupled during this period and reached 10 definitions. Android.Fakealert.10.origin, distributed as a viewer for adult video clips, became the most notable member of the family. When launched, this malicious program would imitate the look and feel of a real anti-virus and notify the user that their mobile device should be scanned for infections. To eliminate the “threats”, which undoubtedly were found in abundance, it would prompt the user to purchase a full version of the program.

|

|

|

|

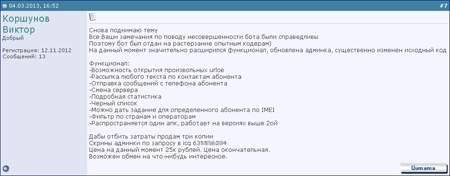

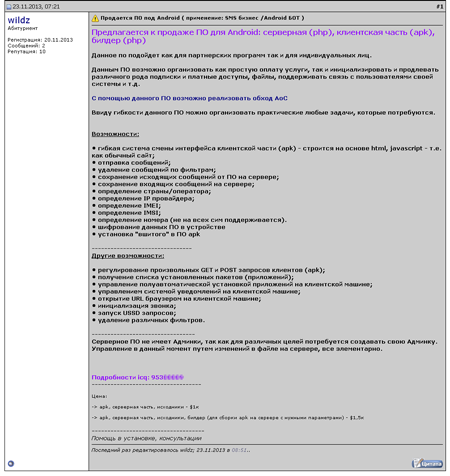

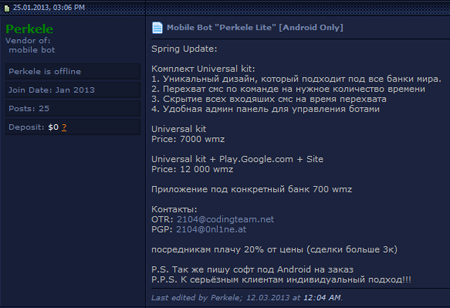

Cybercriminal services: Trojans on demand and hack tools

Last year saw the rapid growth of the cybercrime service market which had slowly begun to emerge in 2012. Currently, the development and sale of various SMS Trojans of the families Android.SmsSend and Android.SmsBot is one of the most common and in-demand illicit services. The Trojans’ authors often offer their customers not only the malicious applications, but also bundled, ready-made solutions that include remote administration panels, as well as software tools to create malicious networks and launch affiliate programmes. The prices vary from several hundred to several thousand dollars.

However, offers springing up in 2013 to implement banking Trojans against users on a multi-nation basis are more dangerous. A Trojan called Perkele, which went on sale in January, serves as a striking example of this trend. Perkele mimics the look and feel of remote banking applications and steals confidential user information, such as SMS messages. The malware's numerous modifications are detected by Dr.Web as Android.SmsSpy programs.

Due to limited sales of copies of the Trojan and its ability to attack users of the 70 largest financial institutions in the world, Perkele could be applied successfully in targeted attacks which may result in substantial financial losses for the affected e-banking customers.

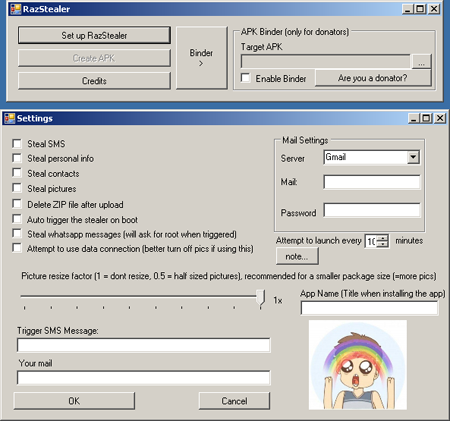

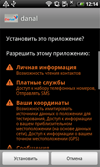

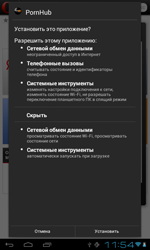

Services related to accessing a wider range of sensitive information belonging to users of Android-powered devices are just as attractive for Internet criminals. Special programs that enable criminals to embed Trojan features in any Android application serve as a good example. Tool.Androrat and Tool.Razielare two such "products" discovered by Doctor Web's analysts. To operate, the first utility used the source code of AndroRat, a freely distributed program for remote access and administration that has been known since 2012 and is detected by Dr.Web as Program.Androrat.1.origin. In the second case, the utility's author made use of their own Trojan spy program, which could either be built into an Android app or compiled into a separate APK package. This malware has been added to the virus database as Android.Raziel.1.origin.

Such utilities are relatively easy to use and enable people with low programming skills to create Trojans for Android. This greatly expands the range of potential users and, therefore, victims.

Strange and unusual threats

Several out-of-the-ordinary programs were discovered amidst the multitude of malware with primitive sets of features. For example, once information from a device's phone book was sent to criminals, the program Android.EmailSpy.2.origin could display an insulting image demonstrating the Trojan authors' contempt towards the device's owner.

The Indian Trojan Android.Biggboss, discovered in March, also appears to be rather unusual. This malware was distributed from various software portals in applications. When installed on a mobile device, it would display a dialog box upon system startup that would notify the user about an important message from an HR department. If the user agreed to view the message, the Trojan would use the browser to load a page containing a fake message from an HR department within the non-existent company TATA India Limited, which has nothing to do with the real TATA corporation. The message included a tempting job description and prompted the user to transfer a specific sum to the criminals' account to hold the job for them.

|

|

Learn more with Dr.Web

Virus statistics Virus descriptions Virus monthly reviews Laboratory-live