July 2014 Virus Activity Overview

Virus reviews | Hot news | All the news | Virus alerts

August 4, 2014

Viruses

Advertising plugins for popular browsers continued to lead among the threats detected by Dr.Web CureIt!. These plugins are malicious extensions that are primarily designed to display unwanted banners on loaded web pages. The variety of such malware is growing. As many as ten malignant plugins are listed among the most frequently detected malware. They include Trojan.BPlug.100, Trojan.BPlug.48, Trojan.BPlug.46, Trojan.BPlug.102, Trojan.BPlug.28, Trojan.BPlug.78 and Trojan.BPlug.79. They all have a similar payload and differ mainly in their specific design features. According to Doctor Web's statistics, Trojan.Packed.24524, which installs other malware and unwanted applications in a compromised system, became the most common threat in July. It accounted for 0.56% of the total number of incidents detected by Dr.Web software, and for 1.59% of the malware detected by Dr.Web CureIt!. Trojan.InstallMonster programs also occupy top positions in this unique ranking of the most common threats.

In email traffic, Dr.Web most frequently detected Trojans that direct users to various bogus sites; these were namely the Trojans Trojan.Redirect.195 and Trojan.Redirect.197, as well as the dangerous malicious program BackDoor.Tishop.122 which was described in one of our previous news publications. You may recall that this Trojan is designed to download other malicious applications onto an infected computer, and, thus, systems lacking anti-virus protection can be turned into bona fide malware menageries.

As far as Doctor Web-monitored botnets are concerned, no significant changes occurred in the past month: botnets comprised of machines infected with Win32.Rmnet.12 (around 250,000 requests per 24 hours were being made to command and control (C&C) servers in one subnet), Win32.Sector (65,000 infected hosts were active daily) and Trojan.Rmnet.19 (an average of 1,100 requests were being made to C&C servers every day) are still operational. The botnet of Macs infected with BackDoor.Flashback.39 currently includes some 14,000 bots.

Encryption Trojans

Today Trojan.Encoder programs perhaps represent the most severe threat to users. The first programs of this kind were discovered in 2006-2007 when users were suddenly confronted with the fact that their important data was encrypted and criminals were demanding a ransom to decrypt it. In those days, such incidents were quite rare, and the encryption technologies adopted by criminals weren't particularly sophisticated, so Doctor Web quickly released a utility to decrypt files affected by the malicious program. However, virus writers doggedly began to upgrade their works by employing more complex encryption routines and perfecting their malware's design. As a result, by January 2009, 39 modifications of encryption Trojans were roaming the wilds of the Internet, and today they number in the several hundreds.

Encryption Trojans are distributed in a variety of ways including email, download links distributed via social networks and messaging programs (often the malware is downloaded onto the victim's computer in the guise of a video codec)—in other words, attackers are using all available means including social engineering technology.

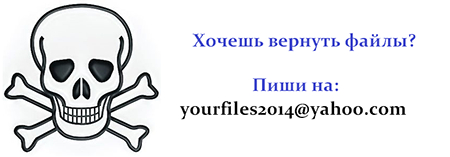

Technologically the Trojans differ in terms of their encryption algorithms and the language in which they were written, but they all operate in a similar way. When launched on an infected computer, the Trojan searches for files stored on disks—documents, pictures, music, movies, and sometimes databases and applications—and encrypts them. Then the malware demands a ransom for file decryption. The demand can be stored on the disk as a text document, made in the form of an image and set as desktop wallpaper, or saved as a web page and added to the autorun list. To communicate with their victims, attackers typically use email accounts provided by free services.

Trojan.Encoder.398 ransom demand

Unfortunately, criminals regularly repack and encrypt malicious files, so the signatures of those files are not added to the virus databases immediately, which means that even modern anti-viruses can't guarantee that a system is 100% secure from encryption Trojans. In addition, modern day encoders employ different routines to generate encryption keys. Sometimes they are generated right in the infected system and transmitted to the criminals’ server, after which the source key files are deleted. In other cases the Trojans acquire keys from the server, but typically the cipher employed remains unknown, and that is why it can be very difficult to recover compromised files (particularly if the Trojan executable is no longer present on the disk) when certain versions of Trojan.Encoder rograms are involved.

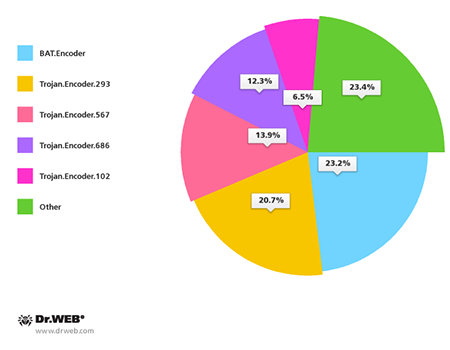

In July 2014, over 320 users whose data was affected by the actions of Trojan encoders contacted Doctor Web's technical support service. Most often the affected files turned out to be encrypted with BAT.Encoder programs—these are Trojans that encrypt files using GPG Cryptography and .bat scripts. Written in Delphi, Trojan.Encoder.293accounts for the second highest number of requests for support. This Trojan performs two-tier file encryption using XOR and RSA ciphers. In addition, many machines have been compromised by Trojan.Encoder.102 which is the predecessor of Trojan.Encoder.293. This Trojan encrypts files using the RSA cipher, which makes it extremely difficult to recover data without a private key. The 32-bit variable in its code also enables the encoder to write its data at the beginning of files whose size exceeds 4 GB and, thus, damage them beyond repair. The pie-chart below provides information about encryption Trojans arranged according to the number of relevant support requests received in July 2014.

July also witnessed the mass distribution ofTrojan.Encoder.686which experts believe to be one of the most sophisticated programs of this kind. The malware has long been encrypting data on computers in Russia, but the recent discovery of an English version of the Trojan indicates that criminals intend to expand their target group. Trojan.Encoder.686 uses rather strong encryption that rules out any possibility of data recovery without encryption keys. The Trojan conceals its presence in a system: first, it encrypts all the files, and only after that does it contact a C&C server to transfer the data. This is a distinguishing feature of Trojan.Encoder.686. Other encoder programs maintain a connection to a C&C server while encrypting files. The C&C server can't be disabled because it resides in the Tor network.

The most effective way to prevent any damage by Trojan encoders is to timely back up all valuable information onto removable media. If your files have been compromised by this malware, follow these steps:

- Contact the police;

- Never attempt to solve the problem by reinstalling the operating system;

- Do not delete any files from the hard drives;

- Do not try to restore the encrypted data on your own;

- Contact Doctor Web's technical support by creating a “Request for Curing” ticket (this service is available free of charge to users who have purchased Doctor Web software);

- Attach a file encrypted by the Trojan to the ticket;

- Wait for a response from a virus analyst. Due to the large volume of requests, it may take some time to receive a response.

July events and threats

Criminals are continuing to employ Trojans to compromise the security of online transactions. In July, security investigators published the results of their research on the banking Trojan Retefe which had been targeting accounts belonging to the customers of several dozen banks in Switzerland, Austria, Germany and Japan. The attack takes place in two stages. First, the victim receives an email offering them the option to install a Windows update program that is, in fact, the REtefe Trojan. The malware lets criminals control traffic on the compromised machine and bypass browser anti-phishing features. Once it has made the necessary adjustments to the infected system’s settings, REtefe deletes itself. After this, no anti-virus can detect an infection. Whenever the victim does any sort of online banking, instead of landing on a legitimate bank website, they end up on a fraudulent web page where they then submit their account information. Then the next stage begins: the victim is offered the option to download and install an Android application that supposedly generates bank account access passwords but, in truth, is another Trojan program. This application covertly redirects inbound SMS from the bank to the criminals' server or another intruder-controlled mobile device. With the victim's credentials and authentication SMS used to confirm online banking operations, the fraudsters have full control over the user's bank account. Various Retefe versions are detected by Dr.Web as Trojan.MulDrop5.9243, Trojan.PWS.Panda.5676 and Trojan.Siggen6.16706, and the Android module is detected as Android.Banker.11.origin.

Attackers are also continuing to target POS terminals. In July, security researchers discovered a botnet comprised of 5,600 computers in 119 countries. It was being used by criminals to steal bank card information. Since February 2014, criminals used infected devices to carry out brute force attacks onto POS terminals. Five botnet C&C servers were discovered. Three inactive ones reside in Iran, Germany and Russia; two operational servers (which began to work in May and June of this year) are also found in Russia. Dr.Web anti-virus software detects the brute force attack module as Trojan.RDPBrute.13.

July events also once again raised questions about the impregnability of Linux. Anti-virus experts published the results of their analysis of Linux.Roopre.1, which is designed to attack web servers running Linux and Unix. The control server can command this multi-purpose modular malware to perform typical malicious tasks such as transferring data, downloading other software, and running jobs. The security analysts gained access to twoLinux.Roopre.1 C&C servers and were able to determine that around 1,400 servers, most of which were located in the USA, Russia, Germany and Canada, were infected.

Mobile threats

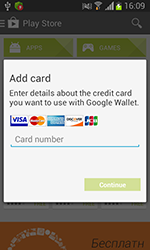

Last month was also rich in new threats to Android. For example, in mid-month Doctor Web's security researchers discovered the dangerous program Android.BankBot.21.origin which steals bank card information from Russian users of Android smart phones and tablets. To do this, the Trojan would mimic a bank card authentication dialogue displayed on top of the running Google Play client and forward the acquired information to criminals. In addition, Android.BankBot.21.origin collected other sensitive information, including all incoming SMS, and could also covertly send short messages when commanded to do so by criminals.

|

|

|

In addition, in July, an entry for a Android.Locker program was added to the Dr.Web virus database. The new piece of ransomware, dubbed Android.Locker.19.origin, was distributed in the US. It locked compromised devices and demanded a ransom for their unlocking. The Trojan severely limited the functionality of an infected device to such an extent that the user couldn’t do anything at all. Therefore, getting rid of the malware was not an easy task.

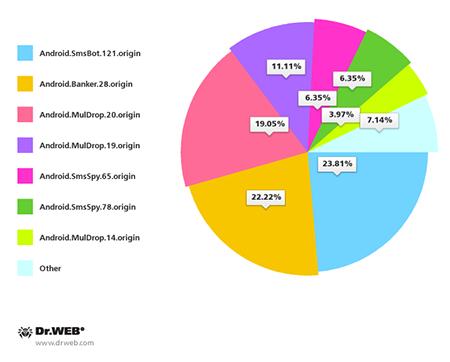

South Korean Android users also came under attack. In the past month Doctor Web registered more than 120 incidents involving spam messages containing Android Trojan download links. The most common threats distributed by means of spam included Android.SmsBot.121.origin, Android.Banker.28.origin, Android.MulDrop.20.origin, Android.MulDrop.19.origin, Android.SmsSpy.65.origin, Android.SmsSpy.78.origin and Android.MulDrop.14.origin.

Learn more with Dr.Web

Virus statistics Virus descriptions Virus monthly reviews Laboratory-live